The role of women in armed guerrilla groups and conflicts has been a focal point of feminist scholarship, especially during the last two decades. However, the case of female combatants provides another example of limitations being placed on women’s agency in both conflict and peace. Mainstream representation of female combatants presents homogenized accounts, which do not go beyond narrow analysis. For instance, dominant discourses generally depict women insurgents as either “mothers, monsters or whores” (Sjoberg and Gentry 2007), categorizing them as transgressive, anomalous, and irrational but never simply as fighters, a depiction which serves to delegitimize their political claims and relates their motives for involvement in armed struggles solely to their womanhood or femininity. Additionally, those scholarly works which study female combatants in the context of feminism, liberation movements, nationalism, and/or paramilitary and political debates are centered on women’s victimhood, as having been recruited by force or being involved for personal reasons. On the other hand, they are only presented in the framework of a political agency (Gowrinathan 2018; Alison 2003; Parashar 2009; Ahall 2012) as challenging hegemonic masculinity by becoming militarized, thereby entering territory traditionally identified as male-dominated (Enloe 2000; 2007). These discourses on the binary framework of ‘victimhood’ and ‘agency’ reflect a reductive attitude towards the complexity of the women’s insurgency from their everyday choices to global politics. Similarly, Kurdish female fighters in non-state armed struggle are portrayed in monolithic and essentialist form as either victimized due to contextual factors or glorified in terms of their bravery against Daesh (also known as ISIL, Islamic State, or ISIS).

Women had been politically active within separate but interconnected Kurdish national movements in four Kurdish regions (Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria) for almost four decades, but Western society only really became aware of Kurdish women fighters when the YPJ (Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, Women’s Protection Union), founded in 2013, fought against Daesh in both Iraq and Syria. The generalized representations of Kurdish female combatants solely relying on interviews with the combatants, political manifestations of the party, press reports and aestheticized visual captures of these female combatants employ ‘homogeneous’ and even ‘orientalist’ portrayals, which overlook intersections between different identities, not only reinforcing stereotypes but also reproducing neo-colonial and orientalist perspectives (see figure 1).

Figure 1- An example for Kurdish women guerrillas’ images circulated by Western mainstream media.

The reality is that, especially since the 1990s, those involved in the Kurdish national armed struggle have sought opportunities to express themselves through a variety of different art forms; it hasn’t simply been a question of fighting. For instance, a school in the form of a guerrilla camp for cultural activities was set up in 1999 for this purpose, the Şehit Sefkan Kültür ve Sanat Okulu (Martyr Şefkan Culture and Arts School), named after one of the early PKK guerrilla fighters, Celal Ercan (nom de guerre ‘Şefkan’). Thus, alongside the ideological transformation from the nation-state to democratic confederalism, the Kurdish national movement started focusing more on cultural activities, such as writing memoirs, autobiographies, poetry, or fictional texts, making music and visual art, and shooting films or short videos. While some of the female guerrillas already had a university degree (mainly in journalism, engineering, law, or sociology), some had not even attended school before their recruitment, and they gained literacy and other skills in the guerrilla bases in the mountains. When I asked Havin, based in Gabar mountain/Iraq, whether engaging with creative production was a common practice amongst combatants, she responded, “it is very, very common, exceptionally, every woman guerrilla write or is engaged with artistic practice. I have seen women who were illiterate before coming to the mountains ending up writing novels, books” (personal correspondence, Jan. 2021). In fact, Kurdish guerrillas are encouraged to write diaries on a regular basis, and former women combatants, even years after leaving the armed struggle, have been greatly affected by their creative experience. Kurdish women guerrillas routinely write their memoirs and diaries. These can be studied within the context of what Lucia Boldrini and Peter Davies (2004) call “fictionalized autobiography and autobiographised fiction”, where personal histories and communal histories collide and are sometimes interwoven (see figure 2). Accordingly, women combatants’ memoirs and diaries cross-literary genre boundaries and elude the usual interpretative grid of autobiographical writing. In this respect, the memoirs, and diaries of women guerrillas both published and accessible on digital outlets and those not yet exposed to the public interrogate genre theory and destabilize the boundaries of autobiographical writings. In the words of one ex-combatant, Avşin, who used to be a singer in a band (personal correspondence, Feb. 2021), “me being in Europe did not differ much from being on the mountains while fighting. Music-making and diary writing became an essence of my soul that I feel like I need to practice every day wherever I am.”

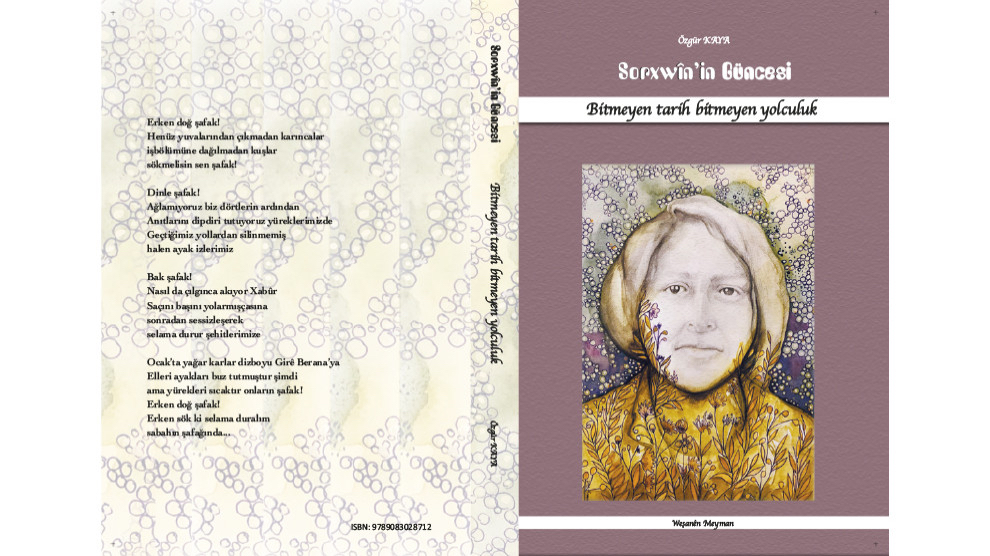

Figure 2- Memoir in the form of fictionalised autobiography of Kurdish woman guerrilla Sorxwîn.

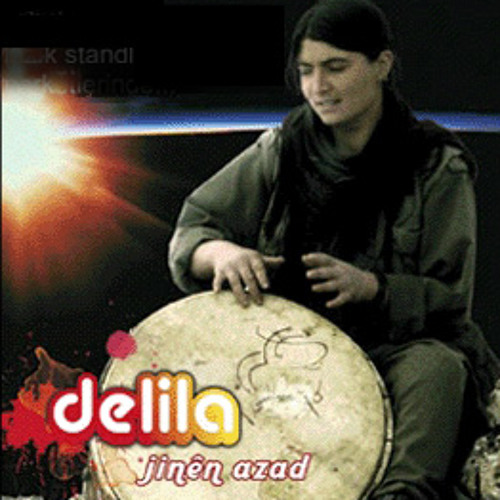

Since the early 1990s, songs and other audio-visual performances recorded and filmed for the purpose of music clips, videos, short films, and feature films in the frontlines and guerrilla units, have been smuggled out and edited within music studios of Kurdish satellite and radio channels mainly based in European cities. Kurdish female combatants bring innovative and personalized musical and rhythmic techniques to this old verbal and performance-based tradition passed on from older generations. The individual, body, and voice all together become the stage for this performance. The lyrics, melodies, and instruments used by them recast cultural practices and musical genres. They create and perform music that combines a combination of both traditional and modern musical elements. For example, Delila Meyaser, a singer and drummer killed by soldiers of the Turkish army in 2008, is considered the best example of this type of music (see figure 3). She sang both romantic and political songs in both Turkish and Kurdish languages. Her musical style and authentic voice had a big influence on other singers and performers. Music made by women guerrillas is drawn from traditional songs, usually involving themes of love and homesickness with govend (folk dance) rhythms. This is not only an attempt to maintain Kurdish musical culture in the face of years of prohibition but also a medium of self-expression or unique voice. Furthermore, handicrafts in the form of folk arts such as spinning wool, knitting traditional Kurdish socks, tablet weaving, and rosary making with natural stones and nettle tree berries also provide first-hand information about the combatants’ use of materials from nature with a modern twist (see figure 4).

Figure 3- Delila Meyaser, singer and drummer, self-trained in guerrillas’ bases, she has both music albums in digital platforms and as in CDs.

Generally speaking, artmaking during warfare is overlooked, downplayed, or denigrated on grounds of biases, lack of subjectivity, and propagandist content or style in artistic productions. Their productions (contra those who disregard these productions, assuming them to be purely political manifestations) are not simply mimetic or witness narratives limited to collective experiences and memories of conflict or war. In most cases, music, poetry, and dance blossom as ‘organic’ aesthetic and cultural forms in the military camps and conflict zones, along with the multidimensionality of the combatants’ individual experience, which involves aesthetic awareness and creativity. Even just bodies, voices, and minds can be sufficient resources to enable artistic creativity to flourish. Thus, it is not that the work of art, in print, paper, and digital form or the “work of art of an experience” (Dewey 1934), is lacking in the battlefields; research open enough to see these works of art as an artistic experience and cultural material is lacking.

Figure 4- A sample of handicraft on rosary and wrist band making by women combatants with the title of “when the guerrilla is not in motion”, from ANF website.

Özlem Belçim Galip is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Oxford. She is the author of Imagining Kurdistan: Identity, Culture and Society (I.B, Tauris, 2015) and Civil Society versus State: New Social Movement and Armenian Question in Turkey (Palgrave, 2020). She is currently at the postproduction stage of her ethnographic documentary film “Anywhere on this Road: Letters to My Unborn Daughter” on Kurdish intellectual women in Europe and her own personal journey as a Kurdish woman migrant, shot in various cities in Turkish Kurdistan along with Germany, England, and Sweden.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 788651.

Bibliography

Ahall, L. (2012). Motherhood, Myth and Gendered Agency in Political Violence. International Feminist Journal of Politics 12 (1): 103-20.

Alison, M. (2003). Cogs in the Wheel? Women in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Civil Wars 6 (4): 37-54.

Boldrini, L. & Davies, P. (2004). Autobiografictions: Comparatist Essays. Comparative Critical Studies 1 (3): 243-63.

Dewey, J. (2005) [1934]. Art as Experience. New York: Penguin.

Enloe, C. (2000). Manoeuvres: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Enloe, C. (2007). Globalization and Militarism: Feminists Make the Link. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Gentry, C. E. & Sjoberg, L. (2015). Beyond Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Thinking about Women’s Violence in Global Politics. London: Zed Books.

Gowrinathan, N. (2013). Inside Camps, Outside Battlefields: Security and Survival for Tamil Women. St Antony’s International Review 9 (1): 11-32.

Parashar, S. (2009). Feminist International Relations and Women Militants: Case Studies from Sri Lanka and Kashmir. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 22 (2): 235-56.