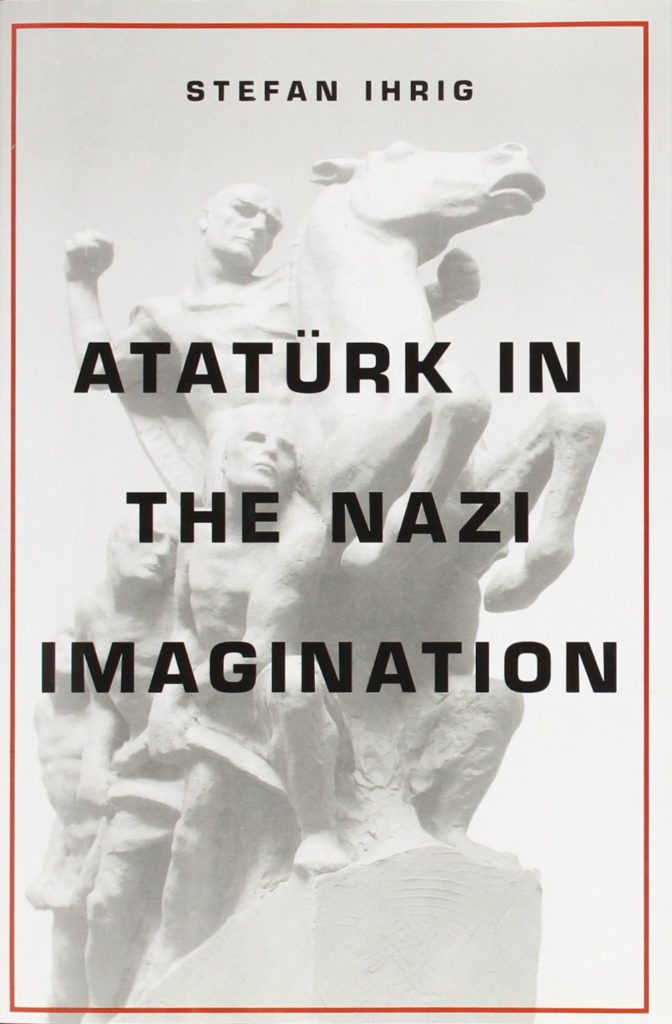

Early in his career, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler took inspiration from Benito Mussolini, his senior colleague in fascism; this fact is widely known. But an equally important role model for Hitler and the Nazi Party was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. In his book Ataturk in the Nazi Imagination, historian and director of Israel’s Haifa Center for German and European Studies Stefan Ihrig reveals that Hitler and Nazi officials were deeply interested in Turkey’s political developments back in the 1920s and were inspired by Ataturk and Kemalism. Ihrig’s well-researched book highlights that Hitler and Nazis admired Ataturk based on three important factors: his “liberation” war against the allies, his charismatic authoritarian leadership and the establishment of a homogenous Turkish state.

Ihrig’s book explores how nationalist German “obsession” with Turkey began with news of Turkey’s “post-war resistance,” which seemed to sharply contrast with the Weimar Republic’s obeisance to the British and French demands. Mustafa Kemal’s refusal to accept the division imposed by the post-WWI Treaty of Sèvres fired the militaristic imagination of German nationalists, who felt humiliated by the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles. As the official Nazi newspaper the Völkischer Beobachter put it in 1921, “Today the Turks are the most youthful nation. The German nation will one day have no other choice but to resort to Turkish methods as well.” Nationalist Germans started asking themselves the question: if the Treaty of Sèvres can be revised, why can’t Versailles?

In focusing on the image of Ataturk as a national hero and modern state-builder, Ihrig examines how charmed Germany’s extreme right and radical nationalists were with Kemal’s government and its “achievements.” According to Nazi intellectuals, the Turkish experience was a reflection of their own anti-Versailles, anti-imperialist, anti-Western struggle. By October 1923, when the Turkish Republic was declared, the Nazi press was focusing more intensely on what it termed “Turkish lessons,” the methods and solutions for nationalist liberation as an example for Germany. The concepts of leadership and charisma, personified in the Turkish leader as the “perfect Führer,” occupied center stage in the propaganda articles of Nazi newspapers in the 1930s. This process also included a deep interest in the “Turkish methods” of dealing with minority questions. In connection with this argument, Ihrig returns to the matter of the Armenian Genocide. Carefully tracking the history of German coverage of the Genocide and the anti-Armenian attitudes of right-wing commentators from the early 1920s, he writes that the German radical right was generally hostile toward Armenians and Greeks.

On his behalf, Hitler not only admired but also sought to imitate Ataturk’s radical construction of a new nation from the ashes of defeat in World War I. The Nazi leader and his associates watched closely as Ataturk defied the Western powers to seize the Turkish government. Following 1919-1923, German right-wing media created propaganda in favor of Ataturk’s military successes and revision of the post-War peace treaties. The “Turkish miracle” was discussed again and again as proof that only a strong leader could change the path of history. By 1924, the Turkish state was praised for creating a “national unitary front,” “national purification,” effective mobilization of the nation, and thus “liberating the nation from Entente oppression.”

On a personal level, Hitler later remarked that in the political aftermath of the First World War, Ataturk was his master, he and Mussolini his students. Ihrig cites Hitler in 1938 saying the following to a delegation of Turkish politicians: “Ataturk was the first to show that it is possible to mobilize and regenerate the resources that a country has lost. In this respect, Ataturk was a teacher; Mussolini was the first and I, his second student.” Moreover, long before Hitler was a national figure the “Turkish Führer” had captivated the imagination of the German right that was trying to recover from what they perceived to be the harsh conditions of the treaties that ended World War I. Later, Hitler himself canonizes Ataturk as “a star in the darkness,” and the Nazi policymakers and the propaganda machine were deeply invested in praising Turkey’s “success” story on at least two counts: actively resisting the British and French and swiftly eliminating the opposition and the non-Turkish minorities.

When it comes to the treatment of minorities, Ihrig shows both the Nazis’ fascination with the ethnic cleansing of minorities that enabled a new homogenized nation and their additional interest in Kemal’s triumph of populist non-democracy. According to Ihrig, the emergence of Turkey as a modern republic from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, which was on the losing side of the Great War together with Germany, was central to the post-war discourse of the German right. “In the eyes of a desperate and desolate Germany,” Turkish nationalists’ ability to resist the dismemberment of the heartland of the empire, ability to secure a homeland, exile and execute opponents and revise a post-war peace treaty imposed on them by the victors was “a nationalist dream come true,” or rather as Ihrig argues “something like a hyper-nationalist pornography.”

Hitler also admired the policy of the Young Turks and later Ataturk in exterminating the minorities and rivals and deporting various ethnic groups from Turkey. Hitler himself often referred to the Armenians, in one article declaring the “wretched Armenian” to be “swine, corrupt, sordid, without conscience, like beggars, submissive, even doglike.” In that sense, according to the Nazi publications, the “sneaky, parasitic and unworthy” Armenians were seen as the “Jews of the orient” who had “stabbed the Turks in the back” during the war. As early as 1924, on the front page of Völkischer Kurier, it was suggested that “what had happened to the Armenians might very well happen to the Jews in a future Germany” in an article written by Hans Trobst, the German mercenary who fought among the Turkish nationalists. At a general party meeting in 1927, Hitler likened the Greeks and Armenians to the Jews because “they have these specific, disgraceful characteristics we condemn in the Jews.”

The destruction of the Armenians was seen as the “one precondition for Ataturk’s success” as defined in Nazi texts. In addition to the cleansing of Anatolia of the Armenians, in order for Turkey to become a state that was “national and only national,” another minority question had to be solved: the Greeks in Anatolia. The exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, which uprooted and dislocated millions of people, was lauded by the Third Reich papers: “something truly unique was accomplished in the sphere of military politics and population science” because it provided the harmonization and standardization of their populations. According to Nazi writers, these double-ethnic cleansings constituted the precondition of the New Turkey. “Only through the annihilation of the Greek and the Armenian tribes in Anatolia were the creation of a Turkish national state and the formation of an unflawed Turkish body of society within one state possible,” argued the Nazi newspaper.

Ihrig’s remarkable research helps the reader realize that Hitler noticed how ruthlessly Turkish governments had dealt with Armenian and Greek minorities, whom influential Nazis directly compared with German Jews. The Nazis included the Armenian Genocide as well as the deportation of Greeks in their reading of ethnic history. What was happening in Turkey during the early 1920s was like a nationalist dream come true for many in Germany. German nationalists and especially Nazis believed that Germany should copy what the Kemalists were doing. The obsession of Nazi officials with Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was not only strategic, but was also deeply personal. In their vision, the New Turkey was an example of a perfectly “cleansed” nation-state. For them, Germany should have followed the “successful” example of Turkey.

The article was originally published in the Armenian Weekly, 14/4/2021

Yeghia Tashjian is a regional analyst and researcher. He has graduated from the American University of Beirut in Public Policy and International Affairs. He pursued his BA at Haigazian University in Political Science in 2013. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a Research Assistant at the Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the Regional Officer of Women in War, a gender-based think tank. He has participated in international conferences in Frankfurt, Vienna, Uppsala, New Delhi, and Yerevan, and presented various topics from minority rights to regional security issues. His thesis topic was on China’s geopolitical and energy security interests in Iran and the Persian Gulf. He is a contributor to the various local and regional newspapers and presenter of the “Turkey Today” program in Radio Voice of Van.