Abstratct

The road to the Georgian-Abkhazian war in 1992-1993 was paved by constantly increasing mutual mistrust, outright rejection of the possible differentiated interests and categorical belief in absolute gain. These structural and perceptional problems continued to undermine the peace negotiations as well. What exactly went wrong in the peace process that thwarted a negotiated settlement for the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict? Are there lessons to learn from the Georgian-Abkhaz peace process for conflict resolution models? This paper asserts that the post-war negotiation period was built on very shaky pillars since the psychological and structural barriers were too strong to overcome. Initially, the perceived absence of the zone of possible agreement as well as the irreconcilability of the reservation values made the high level bilateral negotiations void. The Schlaining Process too as a new model of negotiation to provide bridges between the constituencies and to create an environment of confidence for the political leaders proved insufficient. It is thus argued that difficulties in curtailing psychological and strategic barriers coupled with structural issues and the cognitive misers in both sides have made an inherently uneasy case for both sides even more problematic to resolve.

Keywords: Georgia, Abkhazia, Caucasus, Conflict Resolution, Peace Negotiation

Georgia’s state-building process coincided with secessionist pressures, first from Abkhazia and later from South Ossetia, right after its independence. In a state of constant conflict the search for a lasting peace within a model of territorial integrity shaped Georgia’s early stages of state formation. When the war that erupted in Abkhazia in 1992 came to a standstill and a ceasefire was reached in 1994 a process of bilateral and multilateral peace talks between the parties were initiated. Regional and global actors were involved in this search for a negotiated peace as rounds of talks took place in Moscow, Tbilisi, Sukhumi and Geneva, and the UN, the EU, the OSCE, the US and Russia as well as civil society actors played some parts in these talks without much success. Yet the breaking point for substantial peace talks between the Georgians and the Abkhaz came with the outbreak of war between Georgia and Russia in the summer of 2008 which resulted in the Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the two breakaway republics from Georgia, as sovereign states. Russia’s explicit support for Abkhazia and South Ossetia not only altered geopolitical balance in the region but also shook the ground on which the peace talks were built. Though some forms of talks still take place between the parties to the conflict a substantial peace process has not restarted after 2008. Examining the processes of conflict and peace talks this paper aims to explain why the peace talks have not put an end to the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. What went wrong in the peace process that did not result in a negotiated settlement? Are there lessons to draw from the Georgian-Abkhaz peace process for conflict resolution models?

The roots of the Abkhazian conflict

Transcaucasia is often referred to as a region where suspicion and conflict constantly triumphed over trust and cooperation. This state of affairs has been reinforced by constant interventions of rivaling foreign powers in domestic affairs of the countries in South Caucasia. Therefore, conflicts that arose in the region rarely stayed local as the broader interests and involvement of dominant regional and international actors tended to involve.[1] As such the reason d`etre of the contemporary conflict between Abkhazia and Georgia could not solely be the irreconcilable interests of the local actors. The outbreak of Georgian-Abkhazian war of 1992-1993 and the failure of the subsequent peace negotiations between the parties were brought about, among others, by the tendency to internationalize the dispute in the region by outside powers including, and notably, Russia.

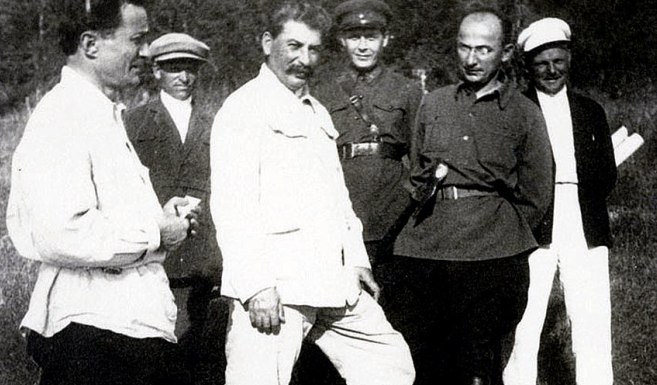

On February 19, 1931 the Sixth All-Georgian Congress of Soviets decided, presumably with Stalin’s consent, to deprive Abkhazia of this status and incorporate it into Georgia as an autonomous republic. In several Abkhaz villages there were mass protests against this change as well as against forced collectivization, then underway across the Soviet Union. Georgian leader Lavrenti Beria mobilized a security police detachment to suppress the protests, but Nestor Lakoba, the first leader of Soviet Abkhazia, managed to defuse the confrontation and avert bloodshed.

The contemporary territorial conflict between Abkhazia and Georgia (echoing all ethnic strife in the post-Soviet Eurasia) is a legacy of an era of Russian domination, and rooted in the nationalities policy of Joseph Stalin that purposely crippled, destabilized and divided the minorities in order to make them totally dependent on Moscow.[2] Even though Abkhazia was firstly integrated to the Soviets as a Republic within the Transcaucasian Federation in 1921, to manifest his divide and control policy in Transcaucasia, Stalin reduced its status to an autonomous republic under the Georgian SSR in 1931.[3] Initially, the Abkhaz ethnic culture was suppressed by both the policies of Moscow and the Georgian SSR so much that not only publishing material in Abkhazian but also using Abkhazian letters and teaching in Abkhaz language were altogether banned, being replaced by Georgian letters and schools during 1944-1945.[4] The justification for such actions was announced by the Georgian SSR as an effort for consolidation but for the Abkhazian point of view this was a process of assimilation.[5]

After glasnost and perestroika the nationalistic movements on both sides escalated unprecedentedly as the control of the Kremlin entered a phase of decline in the peripheries. As a direct result, nationalistic ethnic Abkhazians launched the Likhny Appeal where 30 000 people signed a petition for independence, e.i. the restoration of the pre-1931 status, on March 1989.[6] The Georgian side claimed that the nationalist activists had strong ties with the KGB and the separatists were mobilized by Kremlin to maintain Russian influence over Georgia.[7] The disintegration of USSR in 1991 created an immense power vacuum in the region which made conflict unavoidable in an already tense state of relations. Initially, the repeal of the Abkhazian Supreme Soviet acts by the Georgian State Council and the referendum in Abkhazia in favor of independence provoked the conflict. The military combat eventually resulted with an Abkhazian control of the north-western territories of Gerogia and the subsequent ethnic cleansing of Georgians on 30 September 1993 turning Abkhazia into an unrecognized de facto state.[8] Russian Federation was the first state to recognize Abkhazia on 26 August 2008 after the Russo-Georgian war in early August 2008.[9]

Search for a negotiated settlement

The first direct contact of the warring parties was on May 1994 when they finally agreed to a ceasefire and the creation of a security zone which was to be observed by the United Nations and the Russian Federation.[10] From 1995 to 2000, UN-facilitated a multilateral negotiation process which proved to be a total failure. The mechanism designed for creating a common agenda for resolution quickly became a platform for crisis management and de-escalation of mutual animosity. The main reason for the failure was due to a “structural flaw” in the mediation style of the UN. The Special Representatives erroneously supported the proposal promoted by only one of the parties and rejected the other’s suggestions several times. Consequently, the critical listening approach utilized by the so-called mediator instead of a reflective listening approach further mitigated the already problematic negotiation process since it was too risky for both sides to have their resolution outcomes rejected. However, the Abkhaz and the Georgians strongly pledged to maintain the cease fire, what they perceived as a stable status quo.

As the deficiency of the UN mediation for resolution became obvious, various Georgian and Abkhazian NGO’s -with the help of United Nations Volunteer (UNV) workers, the Helsinki Citizens Assembly and the Austrian Study Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution- organized the January 1997 workshop for the sake of sparking a hope for a peaceful solution.[11] Yet, it wasn’t until late 2000 when the enthusiasm was formulated to a disciplined and continuous dialog process, which was sponsored by the Conciliation Resources (CR) in neutral territories. Even though the following workshops were organized in different cities, the name of the process was named after the debut meeting in the Austrian city of Schlaining.[12]

A new model for negotiating peace: The Schlaining process

The masterminds[13] behind the Schlaining Process had a perception that the conditions for effective negotiations were yet to emerge so they conceptualized a “social infrastructure for peace” through organizing low profile (unofficial) multilateral workshops.[14] Naturally, the Process was designed to operate on multiple (international, political and civic) levels. However, the main emphasis was given to the civic actors in trying to contribute to the transformation of relations within as well as between communities fragmented by violence.[15]

Taking its roots from the cultural diplomacy theory the collaborative civic endeavor was to dilute the dysfunctional effects of high politics. Hence, the organizers were very careful not to repeat the mistakes of the UN who followed a Track 1.5 approach (macro-political process) while the Conciliation Resources team followed a Track II style of negotiation which works for an unofficial non-governmental intervention to prevent conflict. So, the structure of the negotiation was “process oriented” rather than “results driven”.[16] While the organizers sought to respect the vulnerabilities of the parties it also tried to create an environment where they can expand the pie using the added value negotiating. However, for that to occur a brief effort for confidence building was needed to reduce the mutual insecurities. Thus, it was agreed that the meetings were to be without ties, confidential and with no third parties.[17]

From 2000 to 2007 twenty dialogue workshops were organized by Conciliation Resources which was regarded as the most comprehensive initiative for conflict resolution between Georgia and Abkhazia. The process was successful in offering concrete suggestions to politicians and the identification of each other’s position and interests while breaking stereotypes and the misconstrued illusions of “the other side.”[18] Yet, the whole initiative was very prone to suspension or even to regress if the multilateral tensions between Russia, Georgia and Abkhazia escalated. The end of the road was signaled first by the Georgian side as they refused to take part in multilateral negotiations in early summer of 2008. It came as no surprise that the following Russo-Georgian war and their military engagement in Abkhazia the Georgians terminated the Schlaining Process.[19]

Issues at stake

Negotiation is defined as “the method by which two or more parties communicate in an effort to agree to change or refrain from changing their relationship with each other.”[20] Therefore, to understand the negotiation process for this particular complex case creating a structure for analysis is crucial. At least four levels of analysis can be laid out for this conflict: Bilateral relations in regard to rival claims to sovereignty over Abkhazia, Georgian-Russian relations, Russian-Western relations, and Abkhaz-Russian relations.

From the Georgian official perspective, this conflict was the price paid for, firstly, gaining independence from USSR and, secondly, attempting to secede from centuries of Russian influence. Thus, the Georgian policy makers emphasize the de jure territorial integrity under international law[21] as the Georgian parliament considers Abkhazia “under Russian military occupation.”[22] The interest of Georgia hasn’t changed since 1992: to restore their power and prestige while strengthening their socio-economic status. However, the official Georgian position (except the principle of national territorial integrity) has altered quiet frequently. Georgia under Zviad Gamsakhurdia implemented a “Georgia for Georgians” approach. Under Eduard Shevarnadze the approach shifted to a “non-objection” policy which allowed the acceleration of the Schlaining Process. With the Rose Revolution on November 2003 and the subsequent -relative- democratization of the country, Micheil Saakashvili was comfortable to introduce a more inclusive and cooperative approach for the resolution of the Abkhazian conflict. He stressed out that the Georgia that seeks a resolution with the Abkhaz was no longer the same Georgia that fought them and the new Western oriented Georgia merited their voluntary return.

However, this unexpected approach to resolution had a triggering effect on internationalizing the local dispute. The Georgian efforts to join NATO and enhance its ties with the EU were strongly opposed by Russia as this would mean the total decline of Russian sphere of influence in Georgia. The active involvement of the international actors with the justification of peace building in Abkhazia and South Ossetia only served to jeopardize the bilateral negotiations as positions and interests became much more complicated. Also, both the Georgians and the Abkhaz fell into the trap of not taking enough responsibility through exporting the ownership of the conflict`s resolution to their “international allies” which was the Euro-Atlantic bloc for Georgians and the Russian Federation for the Abkhaz. Further on, Georgia added more fuel to the fire lit by Russians by internationalizing the conflict as much as possible while isolating Abkhazia at the same time. The isolation strategy[23] was the opposite of the position Saakashvili stood right after his election and this strategy nullified the efforts of the Conciliation Resources after mid-2006. Nevertheless, the post-2008 position of Georgia -especially after Saakashvili- up to now is regarded to be much more focused on inclusion and cultural diplomacy with incentives such as free healthcare for the Abkhaz in nearby Georgian hospitals and the future ability for the Abkhaz to benefit from the EU visa liberation agreement, instead of staying as an isolated unrecognized state.[24] However, especially with the Russian-Abkhazian integration agreement of 2014 and the military alliance formed between Russia and Abkhazia in 2015, the Georgian officials claim that Abkhazia is becoming a de facto oblast of the Russian Federation and it cedes itself from being a separate actor for negotiation.[25]

The Abkhaz point of view for the conflict is that it was an effort to liberate themselves from decades of Georgian colonialism and demographic domination which they perceived to be even more persistent during late 1980s and early 1990s with the increasingly nationalistic rhetoric of Tbilisi. The Abkhaz interests are the preservation of the de facto independence, the current demographics of Abkhazia and their cultural and lingual identity. Their position has virtually remained unchanged since 1993 as they insist on a nation’s right to self-determination and the impossibility of a reunification with Georgia after such traumas.[26] After the Rose Revolution, the Abkhazians welcomed the democratization and development efforts of Georgia not because it made Georgia attractive to unite with but because it made Georgia more stable and thus less of a threat to Abkhazia.[27] However, the isolation efforts by Georgia and the EU/US after mid-2006 left no choice for Abkhazia but to depend even more on Russians who were more than willing to have it that way. The post-2008 environment made Abkhazia even more reluctant to negotiate with their Georgian counterparts as the Russian recognition with the military and economic aid made the status quo much more attractive for them.

News from Russia set off celebrations in Abkhazia on Tuesday.

What went wrong in peace negotiations?

The negotiation process can only lead to a concrete result if it can bring the civic and official actors together in order to overcome certain (often multilevel) contentions of interests and/or ideas. Even though at first glance it seems that the Abkhazian-Georgian conflict rests upon territorial gains, the reality is that this has much more to do with abstract constructions rather than tangible interests. Experts in the Conciliation Resources argue that “…fear, playing across negotiations and feeding off retelling of past experiences, is a driver of conflict like nothing else”.[28] Thus, the trans-generational trauma experienced by both parties result in psychocultural dramas which can be described as: “competing and apparently irresolvable claims that enhances … contemporary identity, suspicion and fears about an opponent. They are polarizing events whose manifest content involves non-negotiable claims, and rights that become important because of their connections to core metaphors.”[29]

Furthermore, the Schlaining Process involved evident examples of the endowment effect and the tendency for reactive devaluation. The theory of the endowment effect can be applicable for this case due to the fact that the Abkhaz had a perception that they had attained[30] their independence through sorrow and blood thus it cannot be given away no matter what, even if there is an offer too tempting. The latter theory can be observed since the mutual mistrust between two parties repeatedly diminished the apparent value of the proposals for resolution in the eyes of the recipient,[31] just because it was presented by the “enemy”.

Moreover, two somewhat interlinked barriers to negotiation can easily be identified: the psychological barrier and the strategic barrier. Even though the Georgian side eliminated their psychological barriers after the Rose Revolution as a result of the relatively “open society” and their assertiveness to challenge the status quo; the Abkhazian side is still accustomed to the Soviet style of building public opinion, thus a shift in psychological perception of the “other side” is still unlikely. The strategic barrier also exists only in the Abkhaz side but it was a major reason for slowing down the negotiation process. This is due to the fact that, the Abkhaz politicians and civic actors have a sense that they benefited from the status quo, and neither the escalation of conflict nor a solution to it would be at their best interests. Besides, a culture of ‘geopolitical great game’ that prevails among the conflicting parties turns negotiations into an absolute zero-sum process and renders any concession unlikely.

Thus, a combination of the insoluble structural issues such as the virtual lack of the zone of possible agreement and the cognitive misers in both sides made an inherently uneasy case to resolve even more problematic. The Georgians have fallen to the Russian trap of further internationalizing the dispute while isolating the Abkhazian side. The Abkhaz, on the other hand, have been limiting their options due to psychological barriers as they categorically reject the Georgian offer of integrating with the West through an internationally recognized autonomy.

_____________________

Dogacahan Dagi is a graduate student specializing on global governance at Bremen University, Germany. His primary research areas are humanitarian politics and conflict resolution, European governance of migration, refugees in international politics and political theory. He has published research papers in journals including, International Journal of Social Sciences, The Diplomatic Observer, and Liberty and International Affairs.

[1] Jaforova, Esmira. (2014). Conflict Resolution in South Caucasus: Challanges to International Efforts. London: Lexington Books.

[2] Cohen, Ariel. (1996). Russian Imperialism: Development and Crisis. London: Praeger Publishers.

[3] Potier, Tim. (2001). Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

[4] Gvantseladze, Teimuraz. (2013). “Functioning of the Abkhazian Language in Education.”Spekali. http://www.spekali.tsu.ge/index.php/en/article/viewArticle/2/20 (accessed 14 December 2017).

[5] Katz, Zev. (1975). Handbook of Major Soviet Nationalities. New York: Free Pres.

[6] Potier. (2001). Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

[7] Jackson, Nicole. (2003). Russian Foreign Policy and the CIS. London. Routledge. 122

[8] Otyrba, Gueorgui. (1994). “War in Abkhazia.” in National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. Edited by Roman Szporluk. New York: M.E Sharpe, Inc.

[9] Clifford, Levy. (2008). “Russia Backs Independence of Georgian Enclaves.” New York Times. August 26. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/27/world/europe/27russia.html (accessed 30 November 2017).

[10] UN Official Documents. (1994). Security Council Resolution 934 (1994). 30 June. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/934(1994) (accessed 2 December 2017).

[11] Cohen, Jonathan. (2012). “Politics and mediation: The Schlaining Process.” in Mediation and Dialogue in Southern Caucasus. Edited by B. Kobakhia, J. Javakhishvili, L. Sotieva. International Alert http://www.c-r.org/downloads/Politics_Mediation_Part2_201207_0.pdf (accessed 2 December 2017).

[12] Wolleh, Oliver. (2006). A Difficult Encounter: The Informal Georgian-Abkhazian Process. Berlin: Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management.

[13] Martin Schumer was the United Nations Volunteers Programme Coordinator in Georgia/Abkhazia during 1997-2000, and Norbert Ropers was a founding shareholder of Berghof Peace Support.

[14] Cohen, J. (2012). “Politics and mediation: The Schlaining Process.”

[15] Paffenholz, Thania. (2010). Civil Society and Peace Building: A Critical Assesment. London: Lynne Reiner Publishers.

[16] Cohen, J. (2012). “Politics and mediation: The Schlaining Process.”

[17] Zakareishvili, Paata. (2012). “The Schlaining Process: A Georgian Perspective.” in Mediation and Dialogue in Southern Caucasus. Edited by B. Kobakhia, J. Javakhishvili, L. Sotieva. International Alert. http://www.c-r.org/downloads/Politics_Mediation_Part2_201207_0.pdf (accessed 5 December 2017).

[18] ibid.

[19] Barabanov, Mikhail. (2009). “The August War between Russia and Georgia” Moscow Defence Brief. April 4. http://www.webcitation.org/5fm4fGQ5j?url=http%3A%2F%2Fmdb.cast.ru%2Fmdb%2F3-2008%2Fitem3%2Farticle1%2F (accessed 2 December 2017).

[20] Goldman, Alvin L. & Rojot, Jacques. (2003). Negotiation: Theory and Practice. New York: Kluwer Law International, p.7.

[21] Cohen. J. (2012). “Politics and mediation: The Schlaining Process.”

[22] The Republic of Georgia. (2010). “Human Rights in the Occupied Territories of Georgia,” Information Note Distributed by the Delegation of Gergia. OSCE Review Conference – Human Dimension Session, Warsaw, September-October 2010, RC.DEL/186/10. https://www.osce.org/home/73289?download=true (accessed 3 December 2017).

[23] Gegeshidze, Archil. (2008). “The Isolation of Abkhazia: A Failed Policy or an Opportunity?” Concilitation Resources Accords: 69.

[24] Brayman, Lolita. & Pack, Jason. (2017) “Georgia’s options at the Abkhaz border,” New Eastern Europe, February 21. http://neweasterneurope.eu/2017/02/21/georgia-s-options-at-abkhazia-s-border/ (accessed 4 December 2017)

[25] Harding, Luke. (2014) “Georgia angered by Russia-Abkhazia military agreement,” The Guardian, 25 November. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/25/georgia-russia-abkhazia-military-agreement-putin (accessed 4 December 2017).

[26] Gurgulia, Manana. (2012). “The Schlaining Process: An Abkhaz Perspective.” in Mediation and Dialogue inSouthern Caucasus. Edited by B. Kobakhia, J. Javakhishvili, L. Sotieva. International Alert. http://www.c-r.org/downloads/Politics_Mediation_Part2_201207_0.pdf (accessed 3 December 2017).

[27] ibid.

[28] Cohen. J. (2012). “Politics and mediation: The Schlaining Process,” 97.

[29] Ross, Marc Howard. (2001). “Psychocultural Interpretations and Dramas: Identity Dynamics in Ethnic Conflict.” Political Psychology, 22 (1), 157.

[30] Goldman & Rojot. (2002). Negotiation: Theory and Practice.

[31] Ross, Lee. (2008). “Reactive Devaluation in Negotiation and Conflict Resolution.” in Barriers to Conflict Resolution. Edited by K. Arrow, R. Mnookin, L.Ross. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. http://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/child-page/370999/doc/slspublic/Reactive%20Devaluation.pdf (accessed 2 December 2017).