Introduction:

To begin with, the establishment of the Mutasarrifiyya in Ottoman Mount Lebanon during the year 1861 was of great significance. It was introduced in the light of large number of reforms that were taking place within the Ottoman territories during the nineteenth century. In its turn, the Mutasarrifiyya brought some sort of tranquility and political stability to the Mountain, after a long period of Maronite-Druze civil clashes. In this paper, I will shed light on the rule of Dawud Pasha, the first Ottoman-Armenian Catholic mutasarrif of the Mountain, who assumed his office in 1861. In the course of my writing, I will point out to the various challenges that he faced during his rule. Moreover, I will highlight his achievements in the Mountain, and end up by pinpointing his territorial ambitions.

The Mutasarrifiyya and its Privileges:

Among numerous intertwined factors, the Maronite-Druze sectarian skirmishes that started during the 1840s and 1850s, reached their height in the year 1860.[1] These events led to a foreign intervention in order to put an end to the ongoing conflict. An International Commission was formed that consisted of France, Britain, Russia, Prussia, and the Porte that engineered the Mutasarrifiyya in 1861. After a long series of negotiations and meetings, Dawud Pasha was appointed as the governor of this new political regime that held the responsibility of governing the Mountain.[2]

The Mutasarrifiyya had a large number of privileges that distinguished it from other Ottoman administrative regimes. It was agreed that the governor had to be an Ottoman Christian, appointed by the Porte, after receiving the approval of the Great Powers.[3] Moreover, there was an Administrative Council that operated within the borders of the Mutasarrifiyya, formed from twelve Ottoman-Lebanese coming from different religious communities. Furthermore, for the first ten years, the Mutasarrifiyya received an annual subsidy of 30,000 liras from the Ottoman government. In return, no taxes were paid to the Ottoman central treasury.[4]

The local people were also allowed to join the gendarme. They were exempted from military service, and did not pay the bedel-i askeri tax.[5] Moreover, the Lebanese natives had the right of holding governmental positions within the Mutasarrifiyya. Finally, Arabic became the official language that was used within its borders.[6] However, the Mutasarrifiyya had some limitations. It did not have access to the sea nor to any fertile lands. Besides the Beqa’a valley, the coastal cities of Beirut and Sidon fell outside its borders, which forced the governorate to rely on outside ports to import and export its goods.[7]

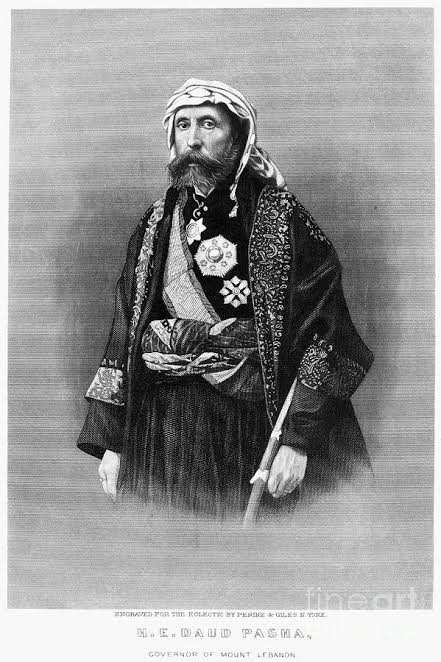

Dawud Pasha’s Background:

Dawud Pasha was an Ottoman Armenian. He was born in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, in 1816.[8] Before being appointed as the Mutasarrif of the Mountain, Dawud held quite important posts representing the Empire in various locations. For instance, he had worked as an attaché to the Ottoman Embassy in Berlin. Later on, he was assigned as the Ottoman consul general in Vienna. Moreover, he was also placed on important bureaucratic positions within the institutions of the Ottoman state. For example, he had worked within the Ottoman Ministry of Interior.[9]

The Political Challenges of Dawud:

The transition to the new mode of governance did not proceed as smoothly as it may appear. The Reglement (Constitution that regulated the Mountain) had allowed each religious sect to secure its seat within the Administrative Council.[10] The Orthodox, Druze and Catholics of the Mountain had recognized the rule of Dawud Pasha, however, there was still some sort of resistance on the part of the Maronites.[11] They constituted the majority of the Mountain. They were greatly dissatisfied because of the political rights granted by the Reglement to the minorities.[12] The aim of the Maronite sect was to dominate over the political scene;[13] its objective was to be governed by its native rulers rather than foreigners. This Maronite political aspiration created a critical situation for France, who was the protector of the Catholics and greatly supported the Maronites. However, the French supported Dawud Pasha on one hand, but they also wanted to satisfy their Maronite clients on the other.[14]

The first mutassarif tried to maintain the unity of the Mountain to the extent possible by relying upon the Ottoman forces.[15] He was accountable to two groups; the Sublime Porte and the International Community.[16] This also created a difficult position for Dawud. He was not able not able to exercise an absolute authority over the northern part of Mount Lebanon. The Maronite Patriarch Bulos Mas’ad and a certain Yusuf Bey Karam were the two main sources of opposition to Dawud’s rule.[17] The latter had gained the popularity of the middle classes and the peasants during the civil war of 1860. The Maronite Church was also on his side.[18] In his turn, Dawud Pasha had offered Yusef Bey Karam to become the Maronite Mudir of Jezzin. However, Karam refused the post because he did not want to be subjected to Dawud’s rule.[19]

After a period of hostility, in 1862, the newly appointed French General Consul Maxim Outrey wanted to cease the conflict between Patriarch Mas’ad and Dawud Pasha. However, Mas’ad did not change his mind. He firmly held his anti-Dawud position, since the Mutasarrif had exiled Karam; the Patriarch’s favorite candidate for the governorship of the Mountain. Moreover, Mas’ad was not able to accept the fact that the region that was once ruled by the Shihabi family was now placed in the hands of a certain foreigner Dawud Pasha.[20] He demanded the supremacy of his people over others, since they outnumbered the Druzes, and received higher education.[21]

During his rule, Dawud Pasha attempted to weaken the power of the Maronite Church as well as to divide the northern part of the Mountain into smaller units. The main project behind these plans was to strengthen his position over the Maronites.[22] In 1864, by the end of his three-year rule as Mutassarif, the Reglement underwent a major revision under the auspices of the French Foreign Ministry known as the Quai d’Orsay. This act by itself intended to come up with a compromise between Dawud Pasha and the Maronites.[23] Among several suggestions, the idea of breaking the Northern district into two separate units, consisting of Batrun and Kisrawan was recommended by the French.[24] In addition to this proposal, the French also advocated the idea of increasing the Maronite political participation within the Administrative Council. They suggested giving the Maronites four-ninth of the seats instead of the one sixth in order to satisfy the latter’s demands.[25] The Ambassadorial Conference of 1864 introduced some changes to the existing Reglement. Three new points were added to it that aimed to strengthen the Mutasarrif’s rule.[26] First, the small administrative councils and the wakils were eliminated. Second, the governor was given the right to directly appoint judges. Finally, as a result of modifying the Constitution only a single sheikh was allowed to represent the whole population of a particular village and govern its affairs. This was contradictory to what preceded it, when every sect within each village elected its own sheikh, who supervised its concerns.[27] Thus, this led to the creation of a more centralized government in the Mountain.

Meanwhile, when Dawud’s rule came to an end in 1864, in his turn Karam was expecting to be appointed as the new Mutassarif.[28] Nevertheless, the Dawud Pasha was allowed to govern the Mountain for five more years.[29] He wanted to force Karam to submit to his rule. Thus, he tried to reconcile with him through the mediation of the Patriarch Mas’ad. Unfortunately, this was not achieved.[30] As a result, in January 1865 Dawud resigned from his post. However, this proposal was rejected by the Porte. Instead, the Pasha received some Ottoman troops that allowed him to place the road between Tripoli and Beirut under his control.[31]

It is noteworthy that with the intention of having a closer watch over the Maronites, Dawud changed his place of residence from Sibni in Shuf to Sarba.[32] In the meantime, the Karamists were still engaged in rebellions during the year 1866. However, upon French interference this uprising was suppressed, and they retreated to Batrun.[33] After a wave of rebellions, Karam was exiled again; this time to Algeria. After his removal from the scene, Dawud started to control the Northern districts of the Mountain in a more effective manner.[34]

Dawud Pasha

Dawud’s Rule in the Mountain:

Prominent historian Kamal Salibi, perceives Dawud as one of the reforming governors of the Mountain. He had organized the gendarmerie as well as built roads and bridges.[35] Dawud Pasha played a pivotal role in establishing the modern communication patterns within Mount Lebanon by taking the initiative of building a 7 km road that stretched from Maamelten to Ghazir. However, he was not able to complete the project that he had once started, because of the eruption of a peasant revolt, due to recruiting the peasants based on the corve (unpaid) method of labor. [36]

Mount Lebanon under Dawud’s rule also witnessed cadastral surveys that were conducted in order to regulate the tax collection by taking into account the number of owned properties. Moreover, he introduced an effective judicial system to the Mountain. He founded eight courts for eight different districts.[37] These courts mainly consisted of “a judge, a deputy judge, and a scribe who assisted them.”[38] However, Dawud Pasha and his successors appointed people from the dominant sects to the posts of judges and deputy judges.[39]

After the 1864 revision of the Reglement, the Administrative Council of the Mountain consisted of twelve members composed of “four Maronites, three Druze, two Greek Orthodox, one Greek Catholic, one Shiite (mutawali), and one Sunni Muslim.”[40] However, the Maronites compared to their larger number, were not well-represented in the Council. In his turn, Dawud Pasha introduced the deputy chairman’s post into the Mountain’s Administrative Council, which was given to the Maronites.[41]

Dawud Pasha wanted to satisfy the Maronite Church, which was dominant in the Mountain. As a result, he assigned Maronite clergy or individuals, who were supported by them to the post of the judges. He also excluded the high-profile Druzes from the government of the Mountain. Moreover, he gave the Maronite religious officials the right to choose the councilors.[42] On the military level, Dawud initially faced some financial burdens that did not allow him to launch his own military forces, as it was permitted to him by the Reglement.[43] However, through the help and support of a certain French captain called Leon Fain, Dawud was able to form armed-forces that were used to maintain the political stability of the region.[44] This newly established unit consisted of a heterogeneous group of people and reached a maximum of 160 men. Among them were “97 Maronites, 40 Druzes, 16 Greek Orthodox, 5 Greek Catholics, and 2 Muslims.”[45] Thus, it gained acceptance from the population. However, regardless of these arrangements, the Maronites still remained the main opponents of Dawud. They refrained from attacking the Northern districts of the Mountain, where their people lived.[46]

The Mutasarrifiya usually faced difficulties in obtaining revenues. The Mountain faced budgetary deficits. In case of such crises, the central government or the treasuries of neighboring provinces covered the shortages.[47] Moreover, subsidies received from the central government were mostly allocated to develop public works.[48] With the aim of increasing the income of the Mutasarrifiya, Dawud Pasha revived the silk production industry.[49]

Dawud’s Territorial Ambitions and Resignation:

After Dawud Pasha was reappointed as the governor of the Mountain in the year 1864 for five additional years, he started demanding areas that fell outside his territories.[50] The fertile Beqa’a valley and Beirut were the two main regions that Dawud Pasha desired to have within the realm of Mount Lebanon.[51] He considered Beirut as ‘the key to Lebanon.’[52] According to Akarli, after Dawud assumed the control of the Mountain, he tended to transform it into an autonomous territory.[53] However, he was constantly asked to abide by the orders transmitted to him by the Ottoman state.[54] As a result of his ambitions in extending the geographical scope of the Mountain, Dawud Pasha became in a conflict with Ottoman reforming minister Mehmed Rasid Pasha.[55]

In 1865, the Porte granted Dawud the western part of the Biqa’a plateau that was capable of producing food for the Mountain.[56] In addition to these demands, he also wanted to elevate the status of the Mutasarrifiyya to the level of a vilayet.[57] When his demands were ignored, Dawud threatened the great powers by submitting his resignation.[58] Finally, in 1868 upon the death of the Ottoman-Armenian Minister Krikor Effendi Aghaton, Dawud Pasha resigned from his post in the Mountain. He took over the latter’s post in Constantinople and became in charge of the portfolio of Ottoman Public Works, which was a position of great significance for the Catholics of the Ottoman Empire.[59]

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the establishment of the Mutasarrifiyya in 1861 was of immense importance. It resulted in the maintenance of peace and order in the Mountain after a long period of destructive war. The experiment of the Mutasarrifiyya started under Dawud Pasha’s rule, who succeeded in reforming the Mountain. Even though, he is blamed for having interests in expanding the Mountain’s territories through annexing some regions to it, however, he can be viewed as the lesser of the evils, because under his rule the Mountain became a better place to live in compared to the previous decades. The appointment of a native Maronite governor to rule the Mutasarrifiyya could have resulted in more violent disturbances.

Bedros Torossian is a senior undergraduate History student at the American University of Beirut. Late Ottoman educational life lies within his area of research. He has recently published an article called “Roles of Turkish and American Orphanages in Influencing Armenian Identities” in

References:

Abu-Manneh, Butrus. “The Province of Syria and the Mutasarrifiyya of Mount Lebanon (1866-

1880).” Turkish Historical Review 4/2 (2013).

Akirli, Engin D. The Long Peace: Ottoman Lebanon, 1861-1920. London: Centre for Lebanese

Studies, 1993.

Salibi, Kamal S. “Dāwūd Pas̲h̲a.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P.

Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Brill

Online, 2016. Reference.

Spagnolo, John P. France & Ottoman Lebanon, 1861-1914. London: Ithaca Press for Middle

East Centre, St. Antonys College, 1977.

Spagnolo, John P. “Constitutional Change in Mount Lebanon: 1861-1864.” Middle Eastern

Studies 7/1 (1971).

Spagnolo, John P. “Mount Lebanon, France and Daud Pasha. A Study of Some Aspects of

Political Habituation.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 2/2 (1971).

[1] John P. Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon 1861-1914 (London: Ithaca Press, 1977), 29.

[2] Ibid, 31.

[3] Butrus Abu-Manneh, “The Province of Syria and the Mutasarriffiya of Mount Lebanon (1866-1880),” Turkish Historical Review 4/2 (2013): 120.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Kamal Salibi, “Dāwūd Pas̲h̲a,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd Edition, P. Bearman, et al., eds., Brill Online, 2016.

[9] Salibi, “Dawud Pasha.”

[10] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 53.

[11] Ibid.

[12] John P. Spagnolo, “France, Mount Lebanon and Dawud Pasha,” International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 2/2 (1971): 158.

[13] Ibid.

[14] John P. Spagnolo, “Constitutional Change in Mount Lebanon: 1861-1864,” Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 7/1 (1971): 37.

[15] Ibid, 35.

[16] Ibid, 36.

[17] Spagnolo, “France, Mount Lebanon and Dawud Pasha,” 150.

[18] Spagnolo, “Constitutional Change,” 34.

[19] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 62.

[20] Spagnolo, “Constitutional Change,” 37.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Spagnolo, “Constitutional Change,” 41.

[24] Spagnolo, “Constitutional Change,” 41.

[25] Ibid, 42.

[26] Ibid, 43.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Engin D. Akerli, The Long Peace: Ottoman Lebanon, 1861-1920 (London: Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1993), 37.

[29] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 1861-1914, 74.

[30] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 101.

[31] Ibid, 102.

[32] Spagnolo, “France, Mount Lebanon and Dawud Pasha,” 152.

[33] Ibid, 153.

[34] Ibid, 158.

[35] Kamal S. Salibi, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd Edition.

[36] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 71.

[37] Akerli, The Long Peace, 134.

[38] Akerli, The Long Peace, 134.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid, 82.

[41] Ibid, 83.

[42] Ibid, 87.

[43] Ibid, 73.

[44] Ibid, 73-74.

[45] Ibid, 74.

[46] Akerli, The Long Peace, 76.

[47] Ibid, 109.

[48] Ibid, 111.

[49] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 40.

[50] Abu-Manneh, “The Province of Syria,” 121.

[51] Akarli, The Long Peace, 39.

[52] Abu-Manneh, “The Province of Syria,” 122.

[53] Akarli, The Long Peace, 40.

[54] Ibid, 39.

[55] Ibid, 40.

[56] Spagnolo, France and Ottoman Lebanon, 159.

[57] Ibid, 160.

[58] Ibid, 164.

[59] Ibid.