Turkey’s modern republican history is fraught with periodic political, economic, cultural and intellectual crises. An heir of a once sprawling and powerful empire, the country has been a scene of competing and often diametrically opposite ideas and visions of its identity, its place in the world and the best way forward. A problem made more complex by the ethnic, confessional and socio-economic diversity of the Turkish society.

Schematically speaking and at the risk of glossing over a complex layer of differentiations, the divide in Turkey is largely between the Kemalist secular ruling elite, who intend to take the country on a putatively Western route to achieve complete modernization, and the largely conservative population who perceives the Kemalist project anathema to its religious and cultural values. The Turkish army have been acting as the guardian of the secular project and intervened time and again in the Turkish politics even before conservative political group came to power.

The nature and respective actors of the above divide, however, underwent a shift after the 1980 military coup and its aftermath. The military, which had been the bastion of Kemalist secularism, began to flirt with Islamist political groups in an effort to weaken the Centre-Left and Centre-Right political organizations.

This new realignment of ties ushered in a new dynamic in the Turkish political landscape: the Islamists were emboldened and pulled the rug from under Centre-Left political forces by co-opting their political agendas and programs and championing the causes of Turkey’s “wretched of the earth”.

The power of the Islamist groups eventually culminated in the coming of the Refah Partısı (Turkish for Welfare Party) to power in 1996 with a conservative politician, Necmettin Erbakan, assuming the office of prime ministry. However, the military was not completely sold to the idea of an Islamist party coming to power and it staged a coup in 1997. Conversely, despite the crackdown following the coup and the disbanding of the Welfare Party, the Islamist made a comeback in the form of the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (Turkey’s Justice and Development Party or AKP) winning elections from 2002 till today.

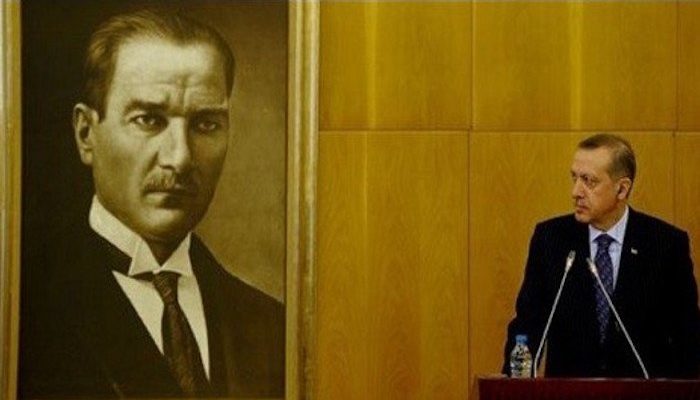

Two factors catapulted the AKP to power; its Islamist ideological commitment; something which appeals to a large section of the Turkish society, and its promise to revamp the fledging economy through the adoption of aggressive neoliberal reforms at micro and macroeconomic levels interlaced with a system of social welfare. Initially, the party under its charismatic leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, delivered on its election campaign promises.

Through the implementation of overarching reforms, instituting sound fiscal discipline, making financial dealing, such as procurement, transparent, encouraging small and mid-level businessmen, locally known as Anatolian Tigers, to have a global competitive edge, the country attracted foreign direct investment, encouraged production of capital and labour, lowered inflation and scored high growth rate. In a sense, the AKP presided over Turkish version of the roaring 2000’s.

AKP’s political achievement was no less than its economic success. It was keen to project an image of an Islamist political force comfortable in its liberal skin. And the world took its word at face value and Turkey was promoted as a poster child of democracy in a region dotted by emirs, monarchs and life-long brutal dictators. It also started peaceful negotiations to solve its “Kurdish problem”.

Similarly, the party announced a new foreign policy framework premised on “zero problems with neighbors”, a concept the foreign policy architect of the party, Ahmed Davutoglu, popularized in his book Stratejik Derinlik or Strategic Depth.

Despite the initial success, however, cracks began to appear in the glossy picture the AKP succeed in projecting initially. According to an acclaimed economist, Daron Acemoglu, from 2007 onwards, the party began to veer from its initial economic policies and rolled back some of the institutional reforms, such as transparency in procurement dealings. It reverted to patronage and favoritism, redirecting investment to its supporters, and introduced populist but economically unsound policies. Instead of private investment and production-based growth, it encouraged unsustainable credit-consumption. As a result, inflation soared, growth slugged and export decreased.

On the political front, the party started to betray its illiberal tendencies. It attacked vocal critics and clamped on independent media. In cahoots with its erstwhile Islamist buddies, such as the Gulenist movement, it charged, imprisoned and purged secular ultra-nationalist military and civilian officials in a trumped up charges of plotting a coup against the state since 2008. After it fell out with the Gulenist movement, following a high profile corruption scandal uncovered by Gulen-affiliated prosecutors in 2013 implicating top officials, including Erdogan himself and his son, the AKP unleashed a heavy crack down on its opponents. In the same year, it brutally responded to the Gezi Park Protests against the AKP’s attacks on secularism, freedom of expression and assembly.

In a bid to sustain himself at the helm of power, Erdogan and his cadres began to campaign for a constitutional reform to institute what they called a presidential system “à la turca”. What is more, the party reneged on its initial position to resolve the “Kurdish problem” peacefully and commenced military offensives against Kurdish forces.

Like on everything, the AKP shred its “zero problem with neighbors” foreign policy facade and gave in to its ideological passions: it broke ties with Egypt after its ideological twin, the Muslim Brotherhood, was removed from power by the military; it jeopardized its initial congenial relations with Syria by supporting a hodge-podge of Islamist extremist forces fighting Assad; it provoked Russia into strong military, economic and diplomatic reactions by downing its airplane; it forced the Iraqi government to complain to the Security Council by sending an army contingent of three thousand troops to the environs of Mosul without the permission of the Iraqi government presumably to train Sunni militias; its relationship with the European Union is deteriorating from bad to worse and its strategic importance to the US is somehow dwindling.

The multiple economic, political, diplomatic, military and security problems in Turkey came to a head with the July 2016 failed coup attempt. In fact, despite its dramatic unfolding, the coup was not unexpected. The AKP had deeply polarized Turkish society, embarked on a dangerous journey of witch-hunt against its opponents, and clamped down on freedom of expression and assembly.

Therefore, some sort of reaction was logically anticipated. Instead of taking stock of things seriously, the ruling party has looked at the coup as a sort of blank cheque to finish what it has already begun; cleansing its opponents and establishing an undisputed authoritarian government. Within four days of the failed coup, it took the insanely disproportional measures of jailing some 40,000 people and purging over 80,000 civil servants.

It closed dozens of media outlets and charged tens of journalists with supporting terrorism. It darted most of its poisonous arrows at the educational and justice institutions. As the result, thousands of teachers, academics, judges and lawyers are either imprisoned or discharged from their job.

Its economy struggling with inflation and slow growth due to an exponential decrease in tourism following its confrontation with Russia and the frequent terrorist attacks, its foreign policies in shambles and its relationship with West deteriorating, its military and security institutions demoralized and truncated to smaller size after the post-coup purges, the war against the Kurds refusing to let up, and the AKP’s relentless attack on democratic rights of its citizens, Turkey has sustained thousand cuts. Whether it will heal these multiple wounds and make a comeback or further slip down the hill is yet to be seen. But there are plenty of reasons not to be optimistic.

————–

Joe Hammoura, “Freedom Eroded: The Precarious State of Turkey”, BullsEye Magazine, Issue 66, December 2016, pp. 4-5.

Joe Hammoura is a specialist in Middle Eastern and Turkish affairs and the co-founder of Leadership for Sustainable Development NGO. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in International Relations at Kocaeli University in Turkey. He holds a Masters degree in International Relations with Honors from the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik – Lebanon (2015). His work focuses on the internal Turkish policies, foreign affairs and its direct and indirect implications on the Middle East. Additionally, he writes for the Legal Agenda Magazine, and is a fellow researcher in Turkish Affairs in the Middle East Institute for Research and Strategic Studies (MEIRSS).