Despite Iran’s increasing political power in the Middle East particularly after the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq and the escalation of the war in Syria, its options, to engage in a direct confrontation with Israel, are dependent on financial and military factors. For Iran, it is costly to engage in a direct military clash with Israel. Therefore, Tehran must attempt a strategy to deter Israel without deploying Iranian troops in Southern Syria.

The policy memo will be divided into four parts.

In the first section, the memo will analyze Iran’s strategy in the region and Syria. This part will address a series of questions that are being circulated in the media and government branches as to whether Iran is a “revisionist” or a “status quo” power or does it follow its national interests far from ideological affiliations. Furthermore, it will address Iran’s “forward-defense” policy and its relations with non-state actors such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and the geopolitical importance of Syria to Iran. The memo’s second part will deal with the decision making process in the IRI. It will highlight the main players and will show the role of Supreme National Security Council in preventing the use of hard power. The third section will analyze Iran’s capabilities, in terms of both strengths and weaknesses. These capabilities will range from financial to military capabilities. Forth, this memo will come up with a list of policies and suggestions for Iran to deter Israel by avoiding a direct confrontation.

Iran’s strategy in the Middle East and particularly Syria

For Iran, the international and regional order is unjust and should be revised. During the early 1980s, IRI was considered a “revisionist” country when it tried to export its Islamic governance system to the neighboring countries. “Revisionist” states seek to change the distribution of power and, regional or international, order for their interests.[1] But events in Syria shifted Iran’s “revolutionary” character and pushed Iran to support President Bashar Al-Assad and become a “status quo” state by maintaining the regional balance against “revisionist” threats coming from other regional or international actors mainly Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the US. Iran’s support to the Syrian states was based on shared interests.

The IRI’s influence was increased with the US lead invasion (2003) on Iraq and the power vacuum that was created after the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s state, Iran’s regional arch-enemy, and was accelerated with the civil war in Syria. Thus Iran found itself no more contained by any regional power. Its greatest neighboring rival was weakened and occupied. With the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq in 2011, the supply route towards Hezbollah and the pathway towards the Mediterranean Sea via Syria and Iraq was unquestionable.

A man carries a giant flag made of flags of Iran, Palestine, Syria and Hezbollah, during a ceremony marking the 37th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, in Tehran February 11, 2016. REUTERS.

With the outbreak of the Arab Uprising in 2011, Iranian leaders welcomed the “Islamic awakening” and expressed solidarity with the Arabs ousting the “despotic regimes”.[2] But as the protest movement reached their ally in the “Axis of Resistance”, Iranian officials were alarmed. From the Iranian perspective, the “Western-led” war on Syria is another attempt to further isolate Iran by weakening or toppling an ally state in Syria.[3] The fall of a strategic ally of Tehran such as Bashar Al-Assad would be a blow to Tehran. It is remarkable to mention that in 2011, former Iranian President Ahmadi Najad tried to open dialogue channels with the Syrian branch of Muslim Brotherhood and pushed President Al-Assad to compromise and form a unity government. Najad’s initiative was blocked by the Supreme National Security Council of Iran.[4] As the Syrian crisis entered its military phase, the Supreme leader and military officials perceived the threat. For Iran, Syria is the only ally and a key supply route to Hezbollah.[5] If Syria would have fallen, they assumed their last stronghold outside their borders would fall, and Iran would be next.[6]

Relations between Syria and Iran are based on shared geopolitical interests. Both oppose Israel, both cooperated to undermine US influence in Iraq, and both have few allies in the region, making them politically dependent on each other. For Tehran, being a player in the regional arena was vital to maintain its self-image as the defender of the Muslim cause by opposing Zionist and imperialist claims in the region. Hezbollah became a key partner in this game.[7] Hezbollah is increasingly growing out of its traditional role as a proxy and becoming more of a partner to both Iran and Syria.[8] The strategic partnership between these three entities is based on shared strategic concerns regarding Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the US.[9]

The real motive that Iran has spent so much of its national capital on a war that is taking place thousands of miles away is best portrayed by the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei who announced during a meeting with the families of Iranian commandos, killed in Syria: “If the ill-wishers and seditionists, who are the puppets of the U.S. and Zionism, had not been confronted [in Syria], we would have stood against them in Tehran, Fars, Khorasan, and Esfahan”.[10] What this tells us is that Iran’s policy toward Syria is not based on expansionist views but rather a pure notion of “balance of threat”, a state’s behavior and actions which is determined by the threats a certain state perceives.[11] Iran’s “offensive” approach towards Syria is based on a defensive policy to contain the enemy abroad rather than at home. In order to protect the domestic stronghold, Iran must deter her adversaries outside its frontiers.[12] This strategy “fight abroad, peace at home” is derived from the sense of insecurity rooted in the eight years of war with Iraq when almost all Western and neighboring countries, except Syria due to its rivalry with Baghdad, supported Saddam to overthrow the “revisionist” order that post-revolutionary Iran was seeking in the region. Thus, after the Iranian-Iraqi war (1980-1988), which cost Iran around 350,000 casualties, pushed IRI to adopt the “Forward-defense” policy. The aim of this policy is to gain influence on weak states, where it can meet its enemies on the battlefield through non-state actors by avoiding direct confrontation against the enemy and thus less human cost.[13]

Thus the strategic alliance with Syria and Hezbollah is important to create a balance of power to counterbalance the US hegemony in the region and deter Israel from attacking Iran.

Decision-making process; the role of SNSC

Despite the perception that the Supreme Leader makes all decisions in security and foreign policy matters, the Supreme National Security Council (SNCS) has an important role in decision making in Iran. Few have given attention to the responsibilities of the SNCS. SNCS is the council for the protection and support of Iran’s national interests such as the territorial integrity, sovereignty and the support of the values of the Islamic revolution.[14] The responsibilities of this council are derived from the constitution.[15] First, it determines the defense and national security policies of Iran within the context of general guidelines that are determined by the Supreme Leader.[16] Second, it enhances the coordination of political, economic and intelligence activities related to the national security and defense policies.[17] Finally, it exploits the materialistic and intellectual resources to address internal and external threats.[18]

The decision-making process is based on a consensus mechanism for setting major domestic and foreign policy.[19] The council is comprised of senior officials from all government branches and key decision-makers such as the foreign, internal, defense and intelligence ministers, military commanders including the Iranian Revolutionary Guardian Corps (IRGC).[20] When it comes to the option to make a choice between hard and soft power usually a diplomatic path overcomes on aggressive military decisions.[21] It is important to keep in mind that IRGC has no vote of veto. However, on issues of hard power, it has a strong voice.[22]

Therefore, although the Supreme Leader and the SNSC are the main decision-makers in foreign policy-making, the role of IRGC is traditionally marginalized by pragmatic civilian officials. This is due to the lack of veto power and decision-making is dependent on the consensus of administrative officials who adhere to diplomacy and cost-benefit calculations rather than military commanders who tend to take hard-power risks. These cost-benefit calculations are derived from Iran’s financial and military capabilities.

Capabilities: Strength and Weakness

Iran needs to be cautious when it comes to decision-making and take into consideration her financial and military capabilities. This section will analyze both IRI’s financial and military capabilities and how the war in Syria is negatively affecting the Iranian domestic politics. While Iran’s regional posture has changed and its influence has grown, internally its economic and social structures have remained weak and vulnerable. Economic sanctions since 2005 have magnified the country’s economic problems.[23] The economy heavily relies on oil revenues, and the country is suffering from high unemployment, high import dependency, and negative growth.[24]

According to Fathollah-Nejad (2018), the protest that erupted in December 2017, have shown that many Iranians were unhappy about their country’s role in Syria. The author mentions that the “war is having an aggravating effect on already growing political and socioeconomic grievances at home”.[25]

Many high ranking former officials also expressed discount with Iran’s intervention in Syria. Former President, Ali-Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani and the former mayor of Tehran, Gholam-Hossein Karbaschi, criticized Iran’s silence on the “crimes committed by the Syrian states against its own people”.[26] Both argued that Iran should seek a diplomatic path in Syria instead of a military one.

We should acknowledge that Iran was caught by surprise when demonstrators started condemning Iran’s role in the region. Demonstrators started to shout “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, I give my life for Iran”, “Leave Syria alone and deal with us”.[27] The domestic demands suddenly took a foreign-policy dimension. Protestors said they are expressing their discontent with Iran’s regional ambitions where their government is spending money outside the country instead of investing it in the infrastructure and the population’s needs at home. It is estimated that the conflict in Syria and Yemen is costing Iran between $6bn and $20bn annually[28] and more than 2100 Iranian and pro-Iranian militias have been killed in Syria.[29]

The 200 fighters acknowledged killed are reportedly Afghan refugees paid to fight in Syria (AFP)

The economic and human costs of Iran’s military intervention in Syria is coming to the surface and Tehran’s leadership must be careful not to cause a domestic explosion while they are concentrating their attention on regional policies.

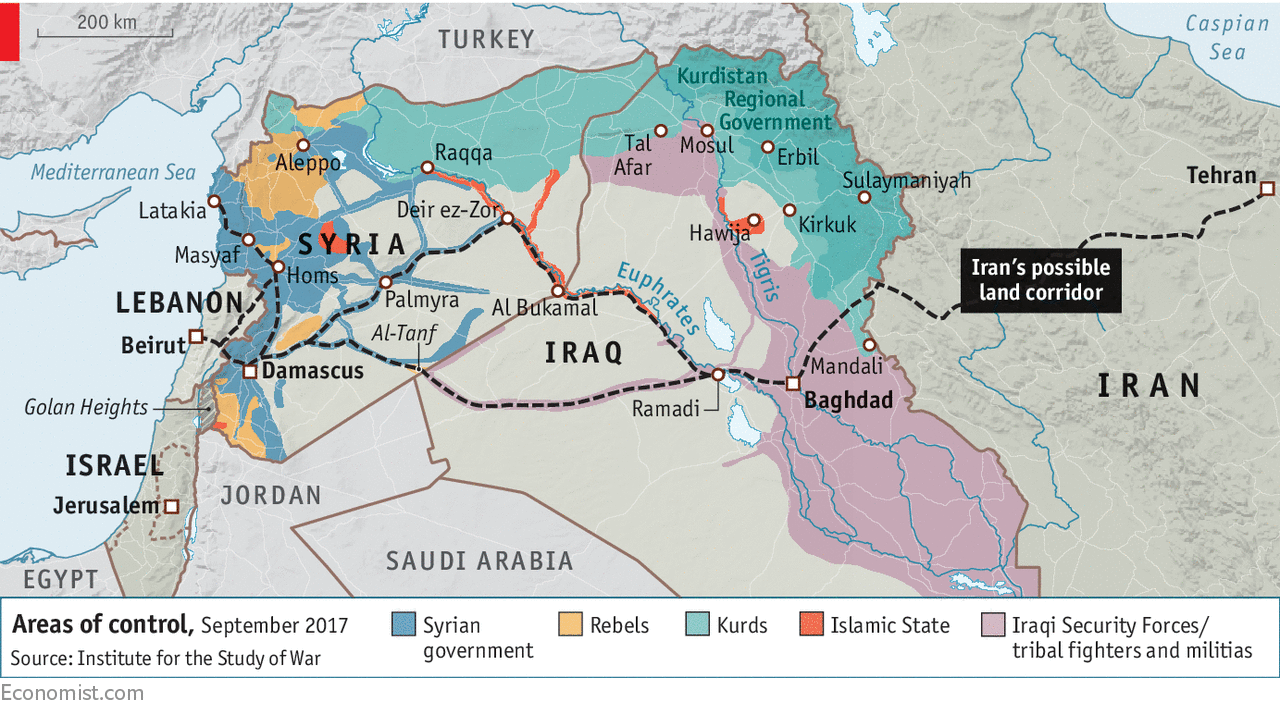

In February 2018, the Institute for National Security Studies of Tel Aviv University published a study about the land corridor that Iran had established connecting Tehran to Syria.[30] The opening of the “land corridor” which was celebrated in the Iranian media, turned out to be no more than a “myth”. The study which is based on the US and Israeli intelligence reports indicate that until now Iran has not used the corridor to transfer its units and supplies out of fear of a possible Israeli and US strikes on its convoys. The study concluded that the Iranians fear will continue in the future.[31]

In spring 2017, the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) took control of the Iraqi-Syrian border from ISIS.[32] Although the US pushed the Kurdish led “Syrian Democratic Forces” to capture the bordering checkpoints, the pro-Iranian Iraqi militias were smart enough to act quickly to block the US initiative and capture al-Bukamal.[33] Although the “land corridor” has been established on the map, Iran has not announced its intention to build a land bridge replacing the air bridge which Iran uses to transfer its supply and units from Tehran to Damascus.

Why is the land bridge important to Iran? This corridor would help to replace the air corridor and to foster the deployment of Iran troops and Shia militias around Syria and supply them with necessary ammunition and high-quality weaponry. Supplying Iran’s troops via air transport is costly for Iran. Thus, diversifying the methods of moving arms and deploying troops. Moreover, this corridor can strengthen Iran’s and Hezbollah’s military capabilities by intensifying their deterrence against Israel.

Iran’s possible land corridor. Source: The Economist

Did Israelis and Americans succeed in limiting Iran’s ambitions? It seems so. In January 2018, the US stated that one of its goals in the Middle East is to put an end to the Iranian dream and block any Iran expansion towards the Mediterranean.[34] The Iranian influence in Syria increased but it’s being tested and contained. Americans have bases in North-eastern Syria and up until now, they prevented President Erdogan to move forwards. The US may use the Kurdish led forces to contain the Iranian militias in Der Zor by capturing certain checkpoints that connect Iraq to Syria. Therefore, it is risky for Iran to divide its troops and send a detachment to Southern Syria while its back in Der Zore is not secured. By distributing out troops on the ground without air cover we will be risking them and give the opportunity to Israel and the US to strike Iranian bases and movements. Moreover, what makes me concerned is Russia’s silence. President Putin is doing his best to reach a diplomatic solution with the Americans and is in good terms with Israel. If Iran initiates attacks on Israel, it could be left out from negotiations. Such a settlement may not be in favor of Iran and could jeopardize its long-term interest and decrease its influence in Syria and the region.

Therefore, the possibility of Iran using the land corridor increases Israel’s threats. Israel will not remain silent watching the Iranian pipeline fueling Hezbollah’s engines.

Although Iran is the fourth military power in the Middle East, its military suffers from modernization and budget cuts.[35] Iran is outgunned by its adversaries. Annual military expenditure 16 billion USD compared to Israel’s 18.5 billion USD (excluding the 3.5 billion military aid from the US) and paled in comparison to KSA’s 76.7 billion USD.[36] Iranian military continues to struggle. Iran’s sizeable defense sectors are incapable of meeting the needs of the army for modern weapons.[37]

Iran heavily invested in ballistic missiles because it was the victim of such kind of weapons during the Iran-Iraq war. For example, its “Shahab 3” missiles range up to 3000 km reaching Eastern Europe and are the main military deterrent force against Israel.[38]

The Shahab-3 missile range. Estimates from 2000-3000 km (AFP)

The role of the Iranian air force is not significant in the Syrian conflict both in terms of quality and quantity compared with the Russian or Western Coalition air forces. The Iranian air force currently has no combat capable fighter jets. A number of former Iraqi Su-22 jets are under refurbishment or modification.[39] While the operative jets are used on the “Persian Gulf” to protect the Strait of Hurmoz from any possible attack.[40] Moreover, the air force is facing a budget deficit. The government is unable to close the gap. Nevertheless, the IRGC commanders are preventing Tehran to allocate more funding for the modernization of the air force and instead are pushing to get more funding to expand their operations in Syria.

Iran’s military options to directly confront Israel are limited.[41] Iran’s naval and air forces are no match of Israel’s. Moreover, despite Trump’s decision to halt the nuclear agreement with Iran, therefore, there is a concern that any retaliation from the Iranian side would push Europeans to side with Washington and Tel Aviv. Furthermore, Iranian air-defense capabilities have been hampered by repeated air strikes from the Israeli side. Israeli sources claim that the latest air strikes destroyed numerous ground-to-ground and anti-air missiles.[42] The attacks on the T-4 airbase in Syria probably destroyed the entire Iranian air-defense system and its drone-launching capabilities.[43] Therefore, how can Iran preserve its interests in Syria?

Policies IRI should adopt to deter Israel and avoid a direct war with her

Based on the analysis above of Iran’s capabilities I have figured out that it is in Iran’s best interest to avoid an uncertain war that could endanger our interests in Syria. US President’s decision to halt the Iranian nuclear deal and John Bolton’s appointment as National Security Advisor to the US President, an advocate of the use of force and “regime change” in Iran, should convince the SNCS to consider these policies if it wants to avoid a major war. [44] IRI should enhance its cooperation with Russia to seek a political solution for the Syrian crisis but also should prepare for war if the US and Israel strike key Iranian positions in southern Syria. In order to continue deterring Israel without directly confronting her on the battlefield the IRI should adopt certain policies:

- IRI must assure Arab states that its military build-up poses no threat to them since its defense doctrine is based entirely on deterrence against Israel.[45] For this, IRI must engage in dialogue with key Gulf States such as Saudi Arabia and UAE to ensure both that Iran has no expansionist agendas and is ready to find a peaceful path for the Yemeni and Syrian crises.

- IRI must support a diplomatic solution in Syria since the crisis could become a trap and a war of attrition that may drain Iran’s financial and military resources. To avoid war in Southern Syria, IRI must coordinate its actions with Russia to avoid any direct clash with Israeli forces. In November 2017, Russia and the US discussed the possibility of creating de-escalation zone in Southern Syria. The Israeli side demanded the withdrawal of Iranian troops and its partners 20 km from the de-militarized zone siding occupied Golan Heights. [46] As a positive gesture, Iran can withdraw from the south and hand its bases to the Syrian or Russian armies.

- IRI must be prepared for any kind of war that Israel and the US may risk in Southern Syria. It must find alternative supply routes and continue to support its non-state partners such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Gaza to build a “balance of threat” and deter Israel. IRI must supply the Lebanese and Palestinian resistance with short and long-range missiles that can target the heart of Israel. It must increase its drone activities near the border to collect intelligence data about the activities and supply routes of the enemy near the Golan Heights.

To conclude, even though the Iranian side must seek for diplomacy and dialogue to end the war in Syria, and coordinate with Russia to resolve the conflict to avoid any kind of direct confrontation with Israel, it must prepare its troops and coordinate with its partners on the ground to retaliate Israel if the other side launches full-scale war.

Yeghia Tashjian is currently pursuing his graduate studies in Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut. He has graduated from Haigazian University in political science. He is a Lebanese-Armenian political activist, researcher, and blogger. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a research assistant at Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the regional officer of Women in War a gender-based think tank.

[1] Raymond Hinnebusch & Anourshiravan Ehtsehami, “The Foreign policy of Middle East states”, Lynne Rienner publishers, USA, 2014, pp. 28-33

[2] Saeed Kamali Dehghan, “Tehran supports the Arab spring…nut not in Syria”, The Guardian, (April 17, 2011), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/apr/18/iran-arab-spring-syria-uprisings, accessed 10/5/2018

[3] Will Fulton, Joseph Holliday and Sam Wyer, “Iranian strategy in Syria”, Institute for the Study of War, (May 2013), http://www.understandingwar.org/report/iranian-strategy-syria, accessed 10/5/2018

[4] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, pp. 1-2

[5] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, pp. 15-16

[6] “If not in Syria, we should have fought Takfiris in Iran: Leader”, Press TV, (January 5, 2017), http://www.presstv.com/Detail/2017/01/05/504915/Iran-IRGC-missile-defense, accessed May 1, 2018

[7] Daniel L. Byman, “Syria and Iran: What’s behind the enduring alliance?” Brookings Institute, (July 19, 2006), https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/syria-and-iran-whats-behind-the-enduring-alliance/, accessed 10/5/2018

[8] Daniel L. Byman, “Syria and Iran: What’s behind the enduring alliance?” Brookings Institute, (July 19, 2006), https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/syria-and-iran-whats-behind-the-enduring-alliance/, accessed 10/5/2018

[9] Daniel L. Byman, “Syria and Iran: What’s behind the enduring alliance?” Brookings Institute, (July 19, 2006), https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/syria-and-iran-whats-behind-the-enduring-alliance/, accessed 10/5/2018

[10] “If not in Syria, we should have fought Takfiris in Iran: Leader”, Press TV, (January 5, 2017), http://www.presstv.com/Detail/2017/01/05/504915/Iran-IRGC-missile-defense, accessed May 1, 2018

[11] Raymond Hinnebusch & Anourshiravan Ehtsehami, “The Foreign policy of Middle East states”, Lynne Rienner publishers, USA, 2014, pp. 28-33

[12] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 10

[13] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 13

[14] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[15] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[16] Kevjn Lim, “National Security Decision-making in Iran”, Comparative Strategy, Volume 34, issue 2, (2015), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01495933.2015.1017347?scroll=top&needAccess=true, accessed 10/5/2018

[17] Kevjn Lim, “National Security Decision-making in Iran”, Comparative Strategy, Volume 34, issue 2, (2015), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01495933.2015.1017347?scroll=top&needAccess=true, accessed 10/5/2018

[18] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[19] Kevjn Lim, “National Security Decision-making in Iran”, Comparative Strategy, Volume 34, issue 2, (2015), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01495933.2015.1017347?scroll=top&needAccess=true, accessed 10/5/2018

[20] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[21] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[22] “Iran’s priorities in a turbulent Middle East”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report N. 184, (April 2018), https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iran/184-irans-priorities-turbulent-middle-east, accessed 3/5/2018, p. 6

[23] Michael Wahid Hanna & Dalia Dassa Kaye, “The Limits of Iranian Power”, Survival, Global Politics and Strategy, (September 23, 2015), p. 180. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2015.1090130?src=recsys. Accessed 15/5/2018

[24] “Iran’s deteriorating economy: an analysis of the economic impact of Western sanctions”, International Affairs Review, the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, (Winter 2018), http://www.iar-gwu.org/node/428, accessed 12/5/2018

[25] Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Iranians respond to the regime: ‘Leave Syria alone’!”, al-Jazeera, (May 2, 2018), https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iranians-respond-regime-leave-syria-180501081025309.html, accessed 9/5/2018

[26] Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Iranians respond to the regime: ‘Leave Syria alone’!”, al-Jazeera, (May 2, 2018), https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iranians-respond-regime-leave-syria-180501081025309.html, accessed 9/5/2018

[27] Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Iranians respond to the regime: ‘Leave Syria alone’!”, al-Jazeera, (May 2, 2018), https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iranians-respond-regime-leave-syria-180501081025309.html, accessed 9/5/2018

[28] Erica Solomon and Najmeh Bozorgmehr, “Iran faces uphill battle to profit from its role in Syria war”, Financial Times, (February 14, 2018), https://www.ft.com/content/f5129c30-0d7f-11e8-8eb7-42f857ea9f09, accessed 2/5/2018

[29] Mahan Abedin, “Hundreds of Iranians have been killed in Syria. Why does Tehran fight on?”, Middle East Eye, ( March 19, 2017), http://www.middleeasteye.net/columns/hundreds-iranians-have-been-killed-syria-why-does-tehran-fight-376313881, accessed 13/5/2018

[30] Ephraim Kam, “Is Iran about to Operate the Land Corridor to Syria?”, INSS, Insight No. 1021, (February 14, 2018), http://www.inss.org.il/publication/iran-operate-land-corridor-syria/, accessed 8/9/2018

[31] Ephraim Kam, “Is Iran about to Operate the Land Corridor to Syria?”, INSS, Insight No. 1021, (February 14, 2018), http://www.inss.org.il/publication/iran-operate-land-corridor-syria/, accessed 8/9/2018

[32] Ahmad Majidyar, “Iran-backed Iraqi militias may send reinforcements to Syria”, Middle East Institute, (January 30, 2018), http://www.mei.edu/content/io/iran-backed-iraqi-militia-commander-we-re-ready-go-syria, accessed 8/5/2018

[33] “Report: Iran uses Tehran-Mediterranean land corridor for military purposes”, Middle East Monitor, (December 18, 2017), https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20171218-report-iran-uses-tehran-mediterranean-land-corridor-for-military-purposes/, accessed 8/8/2017

[34] Ephraim Kam, “Is Iran about to Operate the Land Corridor to Syria?”, INSS, Insight No. 1021, (February 14, 2018), http://www.inss.org.il/publication/iran-operate-land-corridor-syria/, accessed 8/9/2018

[35] Dominic Dudley, “The 10 strongest military forces in the Middle East”, Forbes, ( February 26, 2018), https://www.forbes.com/sites/dominicdudley/2018/02/26/ten-strongest-military-forces-middle-east/#4ac4d13c16a2, accessed 2/5/2018

[36] Dominic Dudley, “The 10 strongest military forces in the Middle East”, Forbes, ( February 26, 2018), https://www.forbes.com/sites/dominicdudley/2018/02/26/ten-strongest-military-forces-middle-east/#4ac4d13c16a2, accessed 2/5/2018

[37] “The Military Balance; The annual assessment of global military capabilities and defense economies”, (2017), p. 376

[38] “The Military Balance; The annual assessment of global military capabilities and defense economies”, (2017), p. 376

[39] Babak Taghvaee, “Syrian war exposes limits of Iran’s air power”, The Global Post, (August 5, 2017), https://www.theglobepost.com/2017/08/05/syrian-war-iran-air-power/, accessed 10/5/2018

[40] Babak Taghvaee, “Syrian war exposes limits of Iran’s air power”, The Global Post, (August 5, 2017), https://www.theglobepost.com/2017/08/05/syrian-war-iran-air-power/, accessed 10/5/2018

[41] Seth J. Frantzman, “Iran wants to retaliate against Israel, but how?”, Jerusalem Post, (April 30, 2018), https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-News/Iran-wants-to-retaliate-against-Israel-but-how-553129, accessed 1/5/2018

[42] Seth J. Frantzman, “Iran wants to retaliate against Israel, but how?”, Jerusalem Post, (April 30, 2018), https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-News/Iran-wants-to-retaliate-against-Israel-but-how-553129, accessed 1/5/2018

[43] Toi Staff, “Israel TV: Monday’s strike on Syria targeted air base Iran was building”, Times of Israel, (April 10, 2018), https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-tv-mondays-strike-on-syria-targeted-air-base-iran-was-building/, accessed 21/5/2018

[44] Walter Shapiro, “John Bolton is a hawk itching for war and few are there to stop him”, The Guardian, (March 23, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/23/john-bolton-hawk-itching-war, accessed 15/5/2018

[45] “If not in Syria, we should have fought Takfiris in Iran: Leader”, Press TV, (January 5, 2017), http://www.presstv.com/Detail/2017/01/05/504915/Iran-IRGC-missile-defense, accessed May 1, 2018

[46] “Israel, Hizbollah and Iran: Preventing another war in Syria”, International Crisis Group, Middle East Report No 182, (February 2018), p. 10-12