George Friedman, The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century, pp. 203 (Doubleday, 2009)

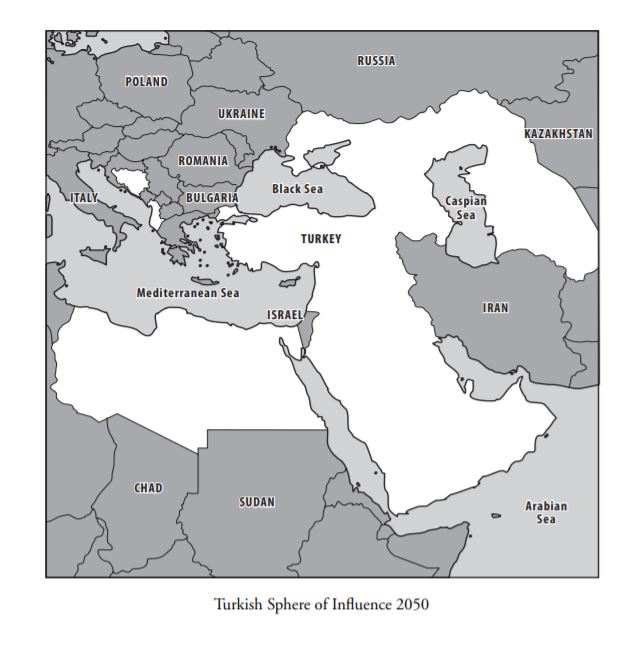

Stratfor is an intelligence-based “research center” often described as the “shadow CIA” whose advisory is to sell intelligence. Its founder George Friedman published a book in 2009 titled “The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century,” which is based on predictions of how the geo-political map of the world will look in 2050. In one of its chapters, the book has published a map of “Turkey’s sphere of influence in 2050.” According to the map, Turkey’s sphere of influence by 2050 will include Greece, Cyprus, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, Gulf countries, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Crimea, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. The book was published during a period when Turkey’s foreign policy under former Foreign Minister Ahmad Davutoglu was being shaped based on the so-called “zero-problem” foreign policy which aimed to ease tensions in neighboring countries starting from the signing of the Armenian-Turkish protocols and ending with consolidating “friendly” relations with Arab countries. During this era, many researchers criticized Turkey’s foreign policy and categorized it as “neo-Ottoman.”It is worth mentioning that when this map was first published, Crimea was not subjected to Russian annexation; part of Nagorno Karabakh and its surrounding areas were not captured by Azerbaijan; and Turkey had not occupied parts of Northern Syria and Iraq; nor had it acquired military bases in Libya and Qatar and extended its influence in Lebanon, Ukraine and Georgia. Now, many Turkish nationalists and government circles believe that such maps are “promising” given the rise of Turkish power in the region. It is within this context that on February 9th the Turkish national TV station TGRT Haber (TRT1) republished the same map. The segment on TGRT Haber was strongly criticized in Russia. Almost 12 years later, this map is recirculating, but this time it is being republished by Turkish media channels. So what has changed in the past 12 years, and is this scenario realistic given the post-“Arab Spring” regional geopolitical changes?

Apparently, showing this old map on national TV was meant to serve the ongoing “neo-Ottoman” and “Pan-Turkic” aspirations of the ruling party in Turkey. Freidman predicted that by 2050, Turkey will expand its power way beyond its current borders to build a new empire, similar to the Ottoman Empire. However, it will be an empire of influence and not an actual occupation. Ironically, Freidman’s map kept Israel, which exists right in the heart of the affected regions, immune to the claimed expansion of the Turkish influence. That is despite Erdogan’s declared ideological animosity to Israel and his repetitive vows to “liberate Jerusalem from the hands of the Jews.” According to the book, the proposed expansion of Turkish influence should rely on three parallel factors. The first factor is Turkey’s soft power diplomacy characterized by culture and religion aimed to exercise influence over these states. The second is Ankara’s success in employing its economic supremacy in the region. The third factor is the natural weakening, over time, of neighboring states, which were expected to go through political turmoil eventually leading to political divisions or, in severe cases, civil wars and Turkish military adventures in these countries.

Speaking of Turkey’s cultural and religious soft power, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan tried to employ this factor in the “Arab Spring.” As Islamist political parties took power in Tunisia and Egypt, Erdogan hailed them and saw the events from the prism of “political Islam” and tried to export the “Turkish governance model” to these countries. Meanwhile, in Syria and Libya, as his model clashed with the society or the ruling party, he tried to gain an advantage from the state disintegration and civil wars by sending his military. However, his dreams were quickly shattered in North Africa, in countries like Egypt and Tunisia, where Islamists lost control. Meanwhile in the Middle East, his rivals including Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) tried to contain the Turkish influence by waging alliances and engaging in proxy wars in Syria and Iraq. Thus, Turkey’s “neo-Ottoman” aspirations quarreled with Arab reactionary and pro-Iranian Shia forces.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s “economic model” lost its credibility in the eyes of Middle Easterners. On the economic supremacy issue, Friedman expected that by 2020 Turkey would have been among the world’s top 10 countries with the strongest economy. Here we are in 2021, and Turkey is ranked as the 19th largest economy in the world. Last summer, the Turkish lira fell to its lowest exchange rate against the US dollar. Regionally, across the Mediterranean Turkey was left alone in economic incentives against Greece, France and Egypt.

In his book, Freidman also claimed that by the middle of the century Turkey’s influence will extend deep into Russia and the Balkans, where it will collide with Poland and the rest of the Eastern European coalition. Turkey will also become a major Mediterranean power, controlling the Suez Canal and projecting its strength into the Persian Gulf. Turkey will frighten the Poles, the Indians, the Israelis and above all the United States. However, all these anticipations failed, where in Egypt President Sisi crushed the Islamist rule; in the Mediterranean, the Israelis, Greeks, French and Egyptians are forming a military axis to contain Turkey; India is searching for partners to balance Turkey; while Russia and China would not hesitate to give more space for Turkey in Central Asia.

Interestingly, the Russians reacted harshly to the circulation of the map in the Turkish media. Since Russia has invested in its relations with Turkey over the years, the republication of a map by Turkish media depicting its expanding influence in areas currently controlled by Russia was embarrassing to Moscow. Russian officials and experts criticized this act and some even warned the Turkish government to stop spreading “pan-Turkic” and “neo-Ottoman” aspirations in or around Russia. First Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Defense Committee Andrei Krasov stated that the Turkish authorities are striving to restore the Ottoman Empire. Commenting on the map showing Turkey expanding its influence deep within Russian territories, Krasov warned, “If they want to test the strength of the Russian spirit and our weapons, let them try.” Russian Senator Vladimir Zhabarov perceived this act as a provocation designed to test Russia’s reaction. “It seems to me that such information is deliberately thrown in to see the reaction. But we won’t react to it.” Meanwhile, in Crimea, Yuri Gempel, the chairman of the Crimean Parliament’s Public Diplomacy and International Affairs Committee, stated to RIA Novosti: “Everything looks most ridiculous and recalls something out of science fiction. One can but advise the Turkish side to abandon dreams of Russian territory, otherwise, they could injure themselves due to such insatiable appetites.”

On February 14, 2021, Russian expert Gevorg Mirzayan, a research fellow of the RAS US and Canadian Studies Institute, published an article titled “How Russia Can Block Erdoğan’s Imperial Ambitions” in the Russian media outlet Vzglyad, later translated by the Middle East Media Research Institute. Commenting on the map, Mirzayan argued that Erdogan’s Pan-Turkic and Pan-Islamist ideologies are threatening Russia’s interests. “Erdogan does not promise to refuse to interfere in the internal affairs of the Russian Federation…Russia should remain alert and not allow Turkey to take over regions under Moscow’s influence. What we (as Russians) should not do is allow (Turkey) a free ride and let the loyalty of Russian regions be ‘switched’ to Ankara,” asserted Mirzayan. The author wrote that Russia must continue cleaning up pro-Turkish organizations in Crimea, the Krasnodar territory and other regions of the Russian Federation.

Explaining his argument, Mirzayan used an old parable about the frog and the scorpion: “Once a scorpion asked a frog to take him across the river on her back. ‘I’m not crazy. As soon as I start swimming, you will sting me,’ the frog replied. ‘But if I sting you, you will drown – and I will drown with you. And I don’t want to die,’ the scorpion reasoned. The frog agreed that this argument was reasonable and logical, so she put the scorpion on her back and swam across the river. But in the middle of the way, the scorpion stung her. The dying frog asked: ‘But why? You will die with me.’ ‘Because I am a scorpion, and this is my nature,’ the sinking scorpion told her.” That is to say in politics, this kind of “nature” exists in the form of ideologies that dictate the behavior of certain political elites. Erdogan’s “neo-Ottoman” or “Pan-Turkic” ideologies do not recognize state borders and are always focused on expansion. Therefore Russia must not let the scorpion cross its borders and has to fight against such ideologies, not only on its territory but also in neighboring countries.

The article was originally published in the Armenian Weekly, 3/3/2021

Yeghia Tashjian is a regional analyst and researcher. He has graduated from the American University of Beirut in Public Policy and International Affairs. He pursued his BA at Haigazian University in Political Science in 2013. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a Research Assistant at the Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the Regional Officer of Women in War, a gender-based think tank. He has participated in international conferences in Frankfurt, Vienna, Uppsala, New Delhi, and Yerevan, and presented various topics from minority rights to regional security issues. His thesis topic was on China’s geopolitical and energy security interests in Iran and the Persian Gulf. He is a contributor to the various local and regional newspapers and presenter of the “Turkey Today” program in Radio Voice of Van.