The denouement of the Turkish referendum melodrama, which has seen the ruling party’s proposal to change the country’s political system from parliamentary to presidential approved by a marginal percentage, marks the death of the Kemalist republic founded in 1923 and the birth of a new one under Recep Tayyip Erdogan. It is unquestionable that Turkey is entering a markedly different era. However, the rough contour of the country’s political landscape will arguably remain intact. Like the Kemalist republic, Erdogan’s republic will most likely be a highly divided one. The identity crisis, the secular vis-à-vis Islamist conflicting aspirations, and the geographical divide will continue to characterize the Turkish body-politic.

Erdogan is not a conciliatory statesman who attempts to bridge political and social divisions. His in your-face rhetorical swagger is what won him popularity among the conservative section of the Turkish society in the first place and it is too precious political capital for him to tone down. He fought tooth and nail to rearrange the deck of the political cards to ensure his tight control of the Turkish state to budge on his authoritarian pursuits. The chronically weak opposition is too anemic to effectively stop the Erdogan train. So what we are most likely to witness in the future is the country sliding to dramatically opposite tendencies: a strong state and a weak civil society. The discursive fusillades vociferously fired by all parties in the run up to and after the referendum portend the difficult time ahead for the country. But a caveat is in order here.

One should take a conscious care not to fall to the orientalist selective and pessimistic alarmism that hastens to validate deeply held prejudice about the East. After the referendum, many western media outlets painted apocalyptic post-referendum scenarios and lamented the loss of a possibility of one Eastern country becoming a Western democracy. One such example is a commentary written for Reuters. The commentary goes: “Sunday’s narrow win for the “yes” campaign for constitutional change in Turkey was perhaps the worst possible result for the country. Turkish democracy, always more aspiration than reality, is now in tatters.”[1] The lamentation is disproportionately latched on the dynamics of Turkey-EU relations. Away from the Orientalist penchant for making anything that happens in the non-Western countries an exception, we need to put what is happening in Turkey in a wider global context.

The political wave on which the ruling AKP and Erdogan have been riding is not that different from the current upsurge of rightist and populist movements all over the world. The rationale for a stronger presidential system the AKP cadres have been peddling for resonates with the preoccupation of populist and rightist political parties in Europe and the United States. The accent of the ruling party campaign for the presidential system was on security, stability, and economic growth. The presidential system, so the argument goes, would streamline decision-making and get rid of the nuisance parliamentary system presents – a factor which allegedly has been hampering the proper working of the Turkish body-politic. A strong executive branch would facilitate quick decision-making which in turn would be good to the country’s economic and democratic development. What is more, the presidential system would strengthen national security and would be more effective in fighting terrorism. [2] To this was added xenophobic, nationalist and religious spices. The latter came out dramatically in the spat Erdogan and his top officials were engaged in with many EU countries in the wake of the latter’s barring of Turkish officials from campaigning for the presidential system in their soil. The referendum campaign was reformulated as a battle between Western crusaders and their local collaborators on one side and genuine Muslim and patriotic Turks on the other.[3]

The counter-arguments submitted mainly by the main opposition parties, the secularist and the pro-Kurdish HDP, against the presidential system is that the shift would inaugurate a disproportionate increase in the president’s authority and thus would open the way for one-man rule. They maintain that presidential system in itself is not a problem but considering the absence of strong judiciary and legislative bodies in Turkey, changing the parliamentary system would mean getting away with checks and balances altogether. [4]

The AKP phenomenon does not only share similar ideological predisposition with other emerging populist parties all over the world but also the historical and ideological crucible out of which it emerged. The fundamental drive which endeared the AKP to a sizeable section of the Turkish population and which catapulted it to power is not only the appeal its message has for conservative elements. As elsewhere, the failure of secular-liberal politics to cater to the needs and aspirations of the common people and its elitist patronization that ride roughshod over the sensibilities and identity affiliations of ordinary people are also part of the reason why the AKP has risen as dominant political force. The point of this digression is to drive home the logic that it is on these historical and ideological shifts the implications of the April 16th referendum should be imbricated.

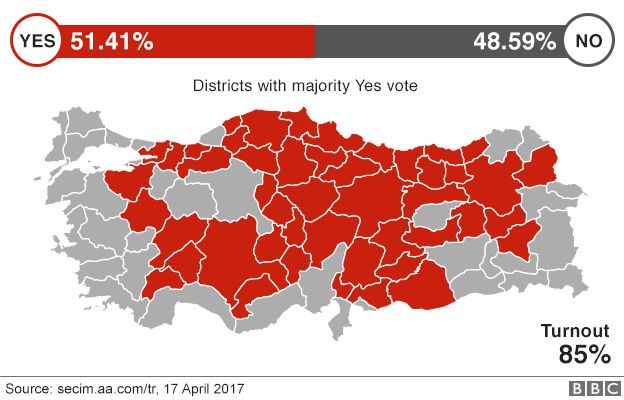

Now, what does and does not the result of April 16th referendum mean for the future of Turkey? First it will mean, inter alia, the scrapping of the role of the prime minister; the president becoming the head of the executive, as well as the head of the state while maintaining ties to a political party; the president having the power to appoint ministers, propose budget, and choose the majority of senior judges; establishing the president’s prerogative to announce state of emergency and dismiss parliament; abolishing the military courts; the parliament losing its right to overlook the performance of ministers while still maintaining its right to impeach the president given a two-third majority vote.[5] These changes will definitely hand the office of presidency sweeping powers. Where this will lead the country to is not something that one can prognosticate with certitude. Considering the heavy-handed manner in which the ruling party has been handling dissent after the July 2016 failed coup attempt one might be tempted to a teleological reading of the future and conclude that the referendum tolls a bell to Turkish democracy. However, what the narrow margin by which the “yes” vote won in the referendum shows is that the future of the country will be highly contested. Despite the wide spread crackdown against free media and dissidents in the wake of the July 2016 failed coup attempt, still over 48.6% of the Turkish population voted against the proposed shift to presidential system. This massive section of the Turkish society will not evaporate to a thin air in the face of a tendency towards absolute authoritarianism. If silencing the conservative section of the Turkish society was not possible in the past, silencing the secular section of the society won’t be possible in the future. If the opposition manages to pull itself together under a charismatic leadership, the balance of power won’t be completely skewed in favor of the authoritarian tendency the ruling party is pushing the country to. So when it comes to the democratic future of the country, things are still up for grubs.

The way people voted in the April 16 referendum expresses the fundamental cleavages within the Turkish society that will likely continue for the foreseeable future. While the Anatolian side of the country voted for the change, big cities like Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir and the Kurds-dominated south and southeastern part of the country voted against the shift to a presidential system. This is symptomatic of the old Turkish division between secular West-looking urban elites and conservative section of the Turkish society. This divide will in all likelihood continue.

What will be the fortune of the political parties in the post-referendum era? The main opposition party, CHP, has incessantly showed itself incapable of mounting effective challenge to the AKP for lack of compelling alternative political vision which Turks across the social divide can buy into. In light of this, one can reasonably expect some form of soul-searching attempts and a movement to reinvention of the party via a new leadership. The ultra-nationalist party, MHP, came out divided from the referendum where some of its members under its chairman voted for the change while many dissented. Those who splintered from the MHP might attempt to form some kind of coalition with the main opposition party or goes on to form another party of their own. The referendum result shows that increasing number of Kurds are supporting the AKP. This, combined with the ceaseless harassment to which it’s been subjected to, will contribute to the further weakening of the pro-Kurdish HDP.

The fact that the April 16 referendum is a turning point in Turkish politics is not debatable. But that should be read as a complete break and a sure harbinger of the country’s slide to the abyss. In fact, what the referendum result confirms is that the country will roughly relive its past, albeit with a different intensity.

[1] Eissenstat, Howard (2017), Commentary: the Real Winners, and losers, in the Turkish Referendum, Reuters, Retrieved From: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkish-referendum-commentary-idUSKBN17J1LV

[2] TRTWORLD (2017), The AK Party’s Arguments for a Presidential System in Turkey, Retrieved From: http://www.trtworld.com/referendum/the-ak-partys-arguments-for-a-presidential-system-334862

[3] Tharoor, Ishaan (2017), The Spat between Turkey and Netherlands is all about Winning Votes, The Washington Post, Retrieved From: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/03/13/the-spat-between-turkey-and-the-netherlands-is-all-about-winning-votes/?utm_term=.5fe6e8ce5dbc

[4] TRTWORLD (2017), op. cit.

[5] BBC (2017), Why Did Turkey Hold a Referendum? Retrieved From: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38883556

Joe Hammoura is a specialist in Middle Eastern and Turkish affairs and the co-founder of Leadership for Sustainable Development NGO. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in International Relations at Kocaeli University in Turkey. He holds a Masters degree in International Relations with Honors from the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik – Lebanon (2015). His work focuses on the internal Turkish policies, foreign affairs and its direct and indirect implications on the Middle East. Additionally, he writes for the Legal Agenda Magazine, and is a fellow researcher in Turkish Affairs in the Middle East Institute for Research and Strategic Studies (MEIRSS).