The ascendency of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) to power in the early 2000’s has ushered in seismic shifts in Turkish economic, political, cultural and ideological tectonic plates. After decades of suppression, marginalization, and sabotage by the Kemalists military elite, the Islamist elements have secured a firm hold on the helm and are determined to make good of this historic opportunity. Showing a significant dent in weakening its political rivals, both secularists and former Islamist bedfellows, the AKP is moving swiftly to recast the Turkish body-politic in its own ideological image. This ideological recasting constitutes, inter alia, redesigning political and cultural insignias of the Republic; tampering with the secularist notion of separating state and religion by opening the state to religious influences and using religion to advance political agendas; promoting a revisionist history which glorifies the Ottoman Caliphate and Empire and laments the Republican break; and cutting Turkey a new geopolitical figure which aspires to position it in a more proactive role in the Islamic world and the Middle East in a manner akin to its former imperial role. These different policy shifts are sometimes referred to as Neo-Ottomanism.

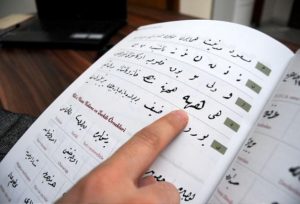

One of the sites of domestic political battles where the AKP wants to pushback is language. As part of its bid to bring the tarnished name of the Ottoman Empire from the gutters back to the center of Turkish political and cultural imagination, it has been working to revive the Ottoman language and make it a compulsory subject in schools. This attempt is directly connected with the ideological battle that have been undergoing since the collapse of the Empire and the establishment of the Republic around the identity of the country. Perhaps, the issue of language and its attendant ideological ramifications is best illustrated by the following incident. On December 2014, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan vowed to include Ottoman language classes in high school curriculum.[1] He is quoted as saying in a speech in Ankara: “There are those who don’t want Ottoman language to be learned and taught. This is a very big danger. Whether they want it or not, Ottoman language will be learned and taught in this country.”[2] His remarks came in the wake of a meeting of Turkey’s National Education Council which discussed so many controversial issues among which were segregating schools by gender; banning cocktail mixing classes in tourism courses; introducing religious classes for kindergartens and the first three years of elementary schools; and making instruction of Ottoman Turkish compulsory in high schools.[3]The Council’s deliberation set off fiery public debates and provoked strong backlash from the opposition and parents.

Erdogan defends importance of learning Ottoman language

The proposal was mainly vehemently opposed by Kemalist, Alevis, Kurds and Zazakis and garnered its sole support from supporters of the ruling party. The rationale put forward by those who are for the proposal of a compulsory Ottoman language classes is of emotional nature. They argue that learning Ottoman will help students to comprehend what is written in the gravestones of their forefathers and historians and researchers would be able to negotiate with ottoman archival documents.[4] It is obvious that proponents of the proposal are looking more for emotive and religious rationale than utilitarian benefits. Conversely, opponents point out to the silliness of the idea and made a black humor out of it. One commentator, for example, quipped that “I was wondering all along where the Turkish youth can be found. Now I know, they are all wandering around in graveyards, trying to decipher their ancestors’ tombstones.”[5] The debates soon took clear ideological lines. A former AKP member for instance wrote that “Now that compulsory Ottoman language instruction in schools is on the agenda, traces of Byzantium seeds will reveal themselves.” Another one tweeted “let’s teach the illiterate Kemalists Ottoman so they can read Atatürk’s words.” Yet another stated “If it were not teaching of Ottomans but Hebrew, they would have gladly accepted the decision.”[6] And one laments “Overnight in 1928, our 900-year history was disconnected from future generations. The Caliphate was abolished. We were asked to wear hats. Our alphabet was changed” and sings praise of the Ottoman language as “Islamic-Arabic” with a clear intent to arouse emotions among conservative sections of the Turkish population.[7]

Those who oppose the proposal took issue with the relevance and utility of making Ottoman language compulsory and raised practical questions about its implementation. Some went straight to what they assumed to be the ideological aim of the proposal. A Cumhuriyet Daily journalist darted a sharp arrow at the proposal by stating that: “Maybe they assume Turkey will get along better with Middle Eastern countries if Ottoman is taught in schools.”[8] Kurd politicians and scholars also voiced their strong disapproval of the proposal and perceived it as a double jeopardy to learn both Modern and Ottoman Turkish while their need is to learn in their vernacular.

After fierce resistance from the opposition and parents, the National Education Council retracted and decided Ottoman language classes to be compulsory for Imam-Hatip religious vocational high schools and elective for other high schools.[9] The debates set off by the Council’s proposal is not and will not be the first one of its kind. The language issue has been part of the grand battle between secularists and Islamists or between modernizers and conservatives since the Tanzimat reforms of the 19th century. When the founder of modern day Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, set out to gear the country towards secularization and modernization, one of the areas he thought he needed to make a drastic change was the language. Around his circle, the Ottoman language was considered a legacy of a stagnated and backward imperial state incapable of carrying and coping with the radical modernizing policies they were determined to implement. Therefore, in 1928, Atatürk ordered the change of alphabets from Arabic to Latin, and the discarding of Arabic and Persian words and replacing them with Turkish words used in the streets. To replace the loan words from foreign languages, large number of original words, which had been in use in the earlier centuries, where revived, and provincial expressions and new coinages were introduced. The transformation met with unparalleled success: In the 1920s, the written language consisted of more than 80 percent Arabic, Persian, and French words; by the early 1980s the ratio had declined to a mere 10 percent.[10]

Atatürk’s language reform, or more appropriately revolution, had many driving rationale behind it. One reason is to mark a radical break from the polyglot, multiethnic, Islamic, clumsy imperial state and usher in a somehow monochromatic ethnically Turkish secular state. Second, related to the first, is the need for a cultural and ideological manipulation in the service of the new political, social and cultural order he was set out to create. Third, related to the second, is to make the Turkish language palatable to westernization towards which he was gearing it. A fourth rationale is more ethnically chauvinistic idea of making the Turkish language the basis of inducing homogeneity at the expenses of other existing languages within the Republic.

The Kemalist reforms were not so successful nor have they been universally welcomed. In addition to the 35 other languages still spoken in Turkey[11], there were always those who felt marginalized, their religious and cultural identities stripped to give way to a presumably more modern Western culture. It is these groups that the ruling AKP represents and gives voice to. Minus the fez, the party seems determined to resuscitate Ottoman socio-cultural, religious and political legacies. The significance with which it looks at these issues is better expressed by the moniker, Osmanlı torunları —Ottoman grandchildren— its cadres and members want to identify themselves with. The same sentiment is expressed when Erdoğan compared the abolition of the Ottoman language to the cutting of jugular veins[12]. In a clear example of how the AKP relates the issue with religion, Erdoğan states that “the religion has a guardian. And this guardian will protect this religion to the end.”[13] This amply shows that what is at stake is not teaching an ancient language whose modern version is completely different to school children for academic reasons. It is something intimately related to the battle for shaping and reshaping the political and cultural spaces of the country. Some of the efforts of the ruling party for sure will have some success. However, the country has travelled so far in the last hundred years that even rebranding with hot red iron is not feasible.

Original source: meirss.org 25/1/2017

Joe Hammoura is a specialist in Middle Eastern and Turkish affairs and the co-founder of Leadership for Sustainable Development NGO. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in International Relations at Kocaeli University in Turkey. He holds a Masters degree in International Relations with Honors from the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik – Lebanon (2015). His work focuses on the internal Turkish policies, foreign affairs and its direct and indirect implications on the Middle East. Additionally, he writes for the Legal Agenda Magazine, and is a fellow researcher in Turkish Affairs in the Middle East Institute for Research and Strategic Studies (MEIRSS).

[1] Tharoor, I. (2014), Why Turkey’s president wants to revive the language of the Ottoman Empire, The Washington Post, Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/12/12/why-turkeys-president-wants-to-revive-the-language-of-the-ottoman-empire/?utm_term=.65797c21e140

[2] Hürriyet Daily News (2014), Ottoman Language Classes to be introduced ‘whatever they say,’ vows Erdogan, Retrieved from: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/ottoman-language-classes-to-be-introduced-whatever-they-say-vows-erdogan.aspx?PageID=238&NID=75329&NewsCatID=338

[3] Tremblay, P. (2014), Erdogan’s ‘New Turkey’ aspires teaching ‘Old Turkish’, Al-Monitor, Retrieved from: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/tr/originals/2014/12/turkey-ottoman-language-alevis-kurds-secular-turks-reacts.html

[4] Yeginsu, C. (2014), Turks Feud over Change in education, The New York Times, Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/09/world/europe/erdogan-pushes-ottoman-language-classes-as-part-of-tradtional-turkish-values.html

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Hürriyet Daily News (2014), op. cit.

[10] Columbia University (1994), Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Retrieved from: http://www.columbia.edu/~sss31/Turkiye/ata/hayati.html#language

[11] Hürriyet Daily News (2013), Thirty-six languages spoken in Turkey, but data needs update, specialist says, Retrieved from: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/thirty-six-languages-spoken-in-turkey-but-data-needs-update-specialist-says.aspx?pageID=238&nID=56469&NewsCatID=339

[12] The Telegraph (2014), Recep Tayyip Erdogan Vows to impose ‘Arabic’ Ottoman lessons in school, Retrieved from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/turkey/11280577/Recep-Tayyip-Erdogan-vows-to-impose-Arabic-Ottoman-lessons-in-schools.html

[13] Ibid.