After the armistice of November 10, Russia gained significant strategic advantages in the South Caucasus. Russia did not just score a military victory by consolidating its military presence in the region, but it is also facilitating the construction of railways and trade networks. On January 11, 2021, a document was signed in Moscow between Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, Armenian PM Nikol Pashinyan and Russian President Vladimir Putin mostly about infrastructure and transport. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan will be able to use each other’s territory for “safe transportation.” Theoretically, economic interdependence would facilitate trade and minimize tensions, however, the geo-economic implications for these trade routes are beyond trade and development.

To implement the trilateral agreement, a working group will be created between Armenia, Russia and Azerbaijan to address the opening of closed borders in the region and to end the blockade of transport and communication links. For this purpose, their governments will set up a dedicated task force headed by their deputy prime ministers for dealing with the opening of the presently-closed borders in the region and the unblocking of economic, commercial and transport communications.

One could note, Armenia already has trade routes with Iran, and Russia via Georgia. Why establish new ones and all passing through Azerbaijan? Why will the transportation route passing via Meghri (most probably) connecting Azerbaijan proper to Nakhichevan be guarded by Russian border guards in Armenia? Who will finance the railway constructions? Who will guarantee the safety of Armenian drivers passing via Azerbaijan? These are questions to which we still do not have answers. However, one thing is clear: Russia wants to have transport links and control over the highways and trade routes, create interdependency in the South Caucasus, pushing the region for greater integration in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

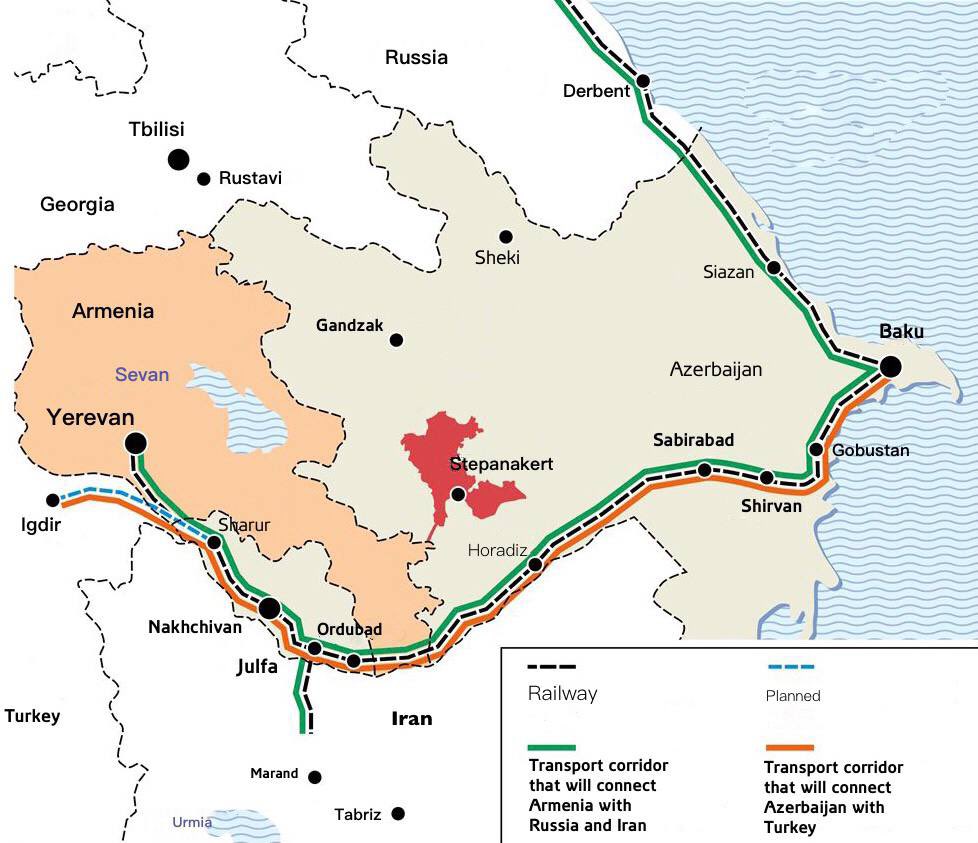

Kommersant.ru has published this map (13/1/2021) showing the prospective road and rail links that will be opened between Armenia and Azerbaijan, linking Armenia to Russia and Azerbaijan to Turkey…essentially reviving the Soviet-era railway closed since 1990. Translated by Jora Karapetyan.

Who will benefit the most and lose from these trade routes?

Azerbaijan, Turkey, Russia and China will emerge as the main winners, Iran and Georgia the main losers, and conditions will depend on Armenia whether it can effectively play an active role in regional trade routes and attract foreign investments.

On January 1, 2021, President Aliyev announced that Baku is constructing a “transport corridor” linking Azerbaijan to Turkey. The railway to the border with Armenia will be ready in two years. The press secretary of the PM of Armenia Mane Gevorgyan commenting on this statement said that Yerevan is interested in the possibility of transporting Armenian cargo to Russia and Iran by rail and road. “Within this context, Armenia is ready to provide communication between Azerbaijan proper and the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic,” she added.

Here it is essential to mention that the November 9, 2020 declaration does not talk about any “corridor in Southern Armenia.” The 9th point of the statement reads: “All economic and transport links in the region shall be unblocked. The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the safety of transport links between western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic to organize the unimpeded movement of citizens, vehicles and cargo in both directions. The Border Service of the FSB of Russia shall exercise control over the transport communication. Subject to agreement by the Parties, the construction of new infrastructure linking the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic with regions of Azerbaijan shall be carried out.” Here the declaration talks about “economic and transport links” and not a corridor with any legal status. It also mentions that all economic and transport links will be unblocked. That is, if Armenia will open a transport/trade link, then Azerbaijan is also obliged to open a link(s) for Armenia. However, what concerns me is that while Armenia is compromising certain sovereignty and letting Russian border troops secure the routes passing within its territory, the trade routes in Azerbaijan may not be safe for Armenian trucks. Will Azerbaijan provide guaranteed security and not abase the Armenians? It is unclear whether these concerns were addressed during Monday’s trilateral meeting in Moscow. What is certain is that Aliyev has scored a strategic victory, and his demands were fulfilled.

Turkey is the main winner after Russia. As Turkey is connected to the South Caucasus via a trade route through the region of Nakhichevan, these trade networks may pave the way in the future for opening up the Armenian-Turkish borders. On December 17, President Putin stated that after reaching an armistice, the next stage will be “normalization of the entire region.” The extent of this “normalization” is not clear and neither is Turkey’s crucial role in it. Already, in his December 1 speech, President Aliyev reported that he had developed a plan for renewed trade and shared it with his Russian and Turkish counterparts and that they responded positively. The plan reportedly is to create a “six-party platform” of Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and, if it met certain (unspecified) conditions, Armenia as well. Aliyev also hinted that Azerbaijan would launch major redevelopment and reconstruction programs, though it is difficult to evaluate the feasibility of Aliyev’s ambitious plan without more details.

By opening the roads towards Azerbaijan, Turkey’s products may cross Central Asia, and for this purpose a railway will be constructed connecting Turkey via Nakhichevan to Azerbaijan proper. The cost of the construction of the railway between Azerbaijan and Turkey, according to the director of Azerbaijan’s Economic Reforms and Communication Analysis Center Vusal Gasimli, is estimated at 434 million USD. Gasimli was pointing to the construction of the Kars-Nakhijevan-Meghri-Zangelan-Baku railway. He said that using Azerbaijan’s potential, Armenia may establish transport communication with Russia in two directions – Gyumri-Nakhijevan-Meghri-Baku and Ijevan-Gazakh-Baku. According to the assessments of foreign sources, the Kars-Gyumri railway (highly important during the Soviet era and closed in 1993) may join the Nakhijevan-Meghri railway construction project.

Yet China with its ambitious BRI will ultimately emerge as a likely partner after these railroads and cargo transportation roads are constructed. In recent years, Beijing has been building and financing transport routes to Europe via Iran and the South Caucasus that bypass Russia. One of these overland routes crosses the Caspian Sea from Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan and onward to Georgia, Turkey, and ultimately Europe. After the recent war, Russia increased its leverage and control over these routes. The trade route between Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan would offer Beijing a second route to Europe in the South Caucasus: the one via Georgia plus this one across southern Armenia (guarded by the Russians) and Nakhichevan. This factor has turned Russia to play a more crucial role in China’s grand economic vision connecting the EAEU member states to China’s transportation corridors. Russia, meanwhile, may have plans to push Azerbaijan to join the EAEU. This may be very difficult at the moment, but in the long run, Azerbaijan will be under intense pressure from Russia. By doing so, Russia will have accomplished one of its goals and minimized Western influence but also would have controlled the energy pipelines.

Bad news for Iran and Georgia. While this initiative would directly connect Turkey to Azerbaijan and boost trade between them, it will reduce the role Iran and Georgia (in the long run) play in regional transportation networks. The proposed Nakhichevan railway is concerning news for Iran. Until now, any shipment from Baku to the Nakhichevan exclave had to traverse northern Iran. Under the new deal, Tehran will lose transit fees and its geopolitical and trade leverage over Baku will decline. For the last three decades, Azerbaijan has been dependent on Iran for transiting energy and other supplies to Nakhichevan. Meanwhile, Iran’s Javan Daily accused Turkey that by sidelining Iran it is pushing a “Western agenda,” and Iran would not accept such a corridor that would jeopardize its geopolitical and geo-economic interests. But the old status quo has been changed and Iran may be forced to revise its policies. Georgia would also lose in the long run as the new transportation route via Armenia will shorten the time for communication and trade. “The shortening of transportation will be profitable for both countries (Azerbaijan and Turkey) in terms of trade while the most important implication of the planned corridor is that Turkey will have a direct connection to the Turkic world,” said dean of Kadir Has University’s Faculty of Economics, Administrative, and Social Sciences Mitat Çelikpala in an interview with Turkish Daily Sabah newspaper. This was a major victory for both Baku and Ankara. The former took Nakhichevan from isolation, while the latter took the first step to achieve its Pan-Turkic dream by opening to the Turkic world. Moreover, Russia also has scored a huge victory, where “The corridor linking Nagorno Karabakh and Armenia and the routes linking Nakhichevan with the rest of Azerbaijan will fall into the hands of Russia,” according to Zurab Batiashvili, a researcher at the Rondeli Foundation, thus bringing Azerbaijan into the Russian economic orbit of influence.

Armenia has limited options around which to maneuver. Yerevan can gain from transit fees and attract Russian and possible Chinese investments. For transportation goods, Armenia uses the Georgian strategic Upper Lars transport corridor which is the shortest and cheapest to reach Russia. However, the mountainous road has many challenges where traffic has been made difficult in summer and winter due to mudslides and avalanches. The other way to reach Russia is through the Georgian port city, Poti, by sea which is longer and more expensive. Furthermore, the north-south highway which Armenia was planning was too expensive and the country lacks railroads to Russia or Iran. Armenia may hope that opening up trade and economic ties will reverse 30 years of its isolation. For that, Moscow cannot work; a new economic, transport and communication infrastructure to interconnect the region will require broader international investment and attention. Armenia has limited resources to finance such projects and will rely on Russian investments. Not surprisingly, the South Caucasus Railway, which is a rail operator in Armenia and is 100-percent owned by Russian Railways, may take the initiative of construction of railways. However, all these ambiguous processes are dependent on further negotiations and agreements. As stated by Richard Giragosian, founding director of the Regional Studies Center (RSC), “The nature of such an Azerbaijani connection through Armenian territory remains dangerously unclear and undefined, raising questions over sovereignty, legal standing and policing.”

These routes will eventually help further deepen ties between Baku and Ankara and consolidate Turkish influence in the region, but under Russian guardianship. These developments are very serious and sensitive, as, with any diplomatic mistake, Armenia may lose its sovereignty on the entire border with Iran. Any potential “provocation” by the Armenian side around these routes may push Azerbaijan or Turkey to raise the issue of trade routes in southern Armenia. This will lead to not only a geopolitical disaster (both for Iran and Armenia), but Armenia will not be more than a client state governed by Ankara/Baku and Moscow. In addition to Turkey and Azerbaijan, Russia directly and China indirectly have scored victories. Russia now through Armenia can extend overland towards Iraq and Syria, while China can safely invest in the infrastructure of the region. The main losers are Iran and Georgia, while Armenia’s status, given its limited space to maneuver, is dependent on decision-makers in Moscow and strong leadership in Yerevan that can inspire some trust in the Kremlin. One thing is clear: the “great game” over the South Caucasus has just begun. Armenia is becoming the center of intersection points of regional trade routes and competition.

The article was originally published in the Armenian Weekly, 13/1/2021

Yeghia Tashjian is a regional analyst and researcher. He has graduated from the American University of Beirut in Public Policy and International Affairs. He pursued his BA at Haigazian University in Political Science in 2013. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a Research Assistant at the Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the Regional Officer of Women in War, a gender-based think tank. He has participated in international conferences in Frankfurt, Vienna, Uppsala, New Delhi, and Yerevan, and presented various topics from minority rights to regional security issues. His thesis topic was on China’s geopolitical and energy security interests in Iran and the Persian Gulf. He is a contributor to the various local and regional newspapers and presenter of the “Turkey Today” program in Radio Voice of Van.