The Origin, success and failure of the Lebanese-Armenian “Third Force” during the intrA-communal cold war (1956-1960)[1]

During the intra-Armenian cold war (1956-1960) it was necessary to have a “third voice” (alternatively known as ‘Third Track’, ‘Third Path’, ‘Third Force’) to build a bridge between the two conflicting Armenian sides. Two major factors catalysed the birth of this “third voice”: the church crisis and inter-communal clashes. This paper will analyze the origins and position of the proponents of the ‘Third Track’ regarding these issues, assess the results and draw conclusions.

In the first part of the paper, I will discuss incidents of international, regional and local (Lebanese) conflict and show how these impacted and shaped the Armenian cold war. Lebanese-Armenian newspapers of the time reported the events from partisan perspectives further inflaming the tense situation. Thus, I have researched the local Armenian dailies, Aztag, Zartonk and Ararad to shed light on the church crisis of 1956 and the clashes that took place in Armenian neighborhoods in 1958.

In the second part of the paper, I will discuss the “Third Voice”, basing the discussion on the Beirut-based Spurk weekly. I will highlight its objectives and aims regarding the hot issues of the time: church crisis, relations with the fatherland, inter-communal clashes, etc. I will conclude my paper with an assessment of the achievements of the ‘Third Voice.’

Factors that led to the Formation of THE “Third Force”

- 1. The Cilician Church Crisis

In this section I will briefly talk about the crisis of the Catholicosate of Cilicia, located in Antelias. The crisis of the Catholicosate of Cilicia was a blow for Armenians throughout the world. Due to the crisis a schism developed and the hierarchic authority of the Armenian Apostolic (Orthodox) Church was challenged. As a consequence, Armenian Apostolic churches in Syria, Lebanon, Iran, Greece and the USA took sides with or against the newly elected Catholicos for the See of Cilicia, Zareh, and shifted their loyalty either to the Catholicosate of All Armenians at Etchmiadzin in Soviet Armenia or the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias. Prior to the election of Archbishop Zareh as catholicos of the Sea of Cilicia the seat was vacant for four years as the Armenian political parties failed to reach a compromise after the death of Catholicos Karekin I in 1952. Cold War pressures sharpened intra-Armenian political disputes in the Middle East in the last years of Karekin’s reign. His relations with the anti-Soviet Tashnag leadership (which had supported his election) now cooled. After Karekin’s health began to deteriorate in 1950, Soviet leaders in Moscow were concerned that a pro-Tashnak clergyman might end up being his successor. In 1951, they pushed the Catholicos of all Armenians in Etchmiadzin, Kevork, to formally write to Catholicos Karekin I in Lebanon and suggest appointing and ordaining a successor (acceptable to the Soviet administration) during his own lifetime. Catholicos Karekin refused this offer, seeing in it a violation of the internal religious freedoms traditionally enjoyed by the catholicosates of both Etchmiadzin and Cilicia. Eventually, Karekin’s death in 1952 was followed by a four-year struggle over his succession, ending in a victory for the Tashnag-supported candidate.

In 1956, based on communal, local and regional calculations, the Tashnag Party realized it was the proper time to challenge the power of Etchmiadzin and to take the church outside the control of the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin and the “pro-Soviets.” The party took the initiative to change the conventional intra-Armenian balance.

Criticism of religious ideology was a part of this tug-of-war. Zartonk,[2] for instance, published reports and quotes of Tashnag intellectuals such as Michael Varantian, who criticized the church and religion and claimed that “religion hinders the progress of a nation.” Aztag[3] reacted by publishing the “atheist” ideology of Communism and detailed how Communists destroyed Armenian churches and exiled and deported priests from Armenia. Aztag went further and accused religion and the church under Soviet rule of being opium and a brainwashing machine.[4] The article even sited Karl Marx’s and Vladimir Lenin’s quotes in order to blackmail the rival Armenian political parties who backed “anti-religious” Communist rule in Armenia.

As the election of the Catholicos was underway, clashes occurred in the Catholicosate of Antelias. Zartonk reported the clashes:

From the day when the council of archbishops in the Cilician Catholicosate, dismissed archbishop Khoren, the Tashnag leadership and its puppets, Khoren, Zareh, Ghevont and other archbishops, started systematically to create a “criminal environment.” But since an army needs a commander, this commander was archbishop Zareh who declared himself “elected Catholicos” and gave orders to dismiss his opponents… . Meanwhile, Thursday, 26 July 1956 around 4:30 p.m., a fight broke out in the Catholicosate hall and a bishop fell and sustained an injury to his head. Yesterday evening around 50 gendarmes were dispatched [to the premises of the Catholicosate] to maintain security in the church and protect it from “Tashnag hooligans”. In the evening bishop Knel Djeredjian was admitted to the American Hospital as he had lost a great deal of blood[5].

On 2 September 1956 the elected Catholicos, Zareh, was consecrated by three archbishops; one of them was a Syriac as the other Armenian archbishops boycotted the consecration. In response, Armenian opposition parties and independents issued a statement:

- We will be the uncompromising protectors of the unity of the Armenian Church.

- We see the church council of Antelias as the only legal representative.

- We claim that archbishop Zareh violated the laws of the church and used illegal means and force to reach a higher position.

- We will unite our forces to put an end to the occupation and liberate the church.

- We will continue our church life and preserve its unity and protect the interests of the church.

- We announce that the action taken by archbishops Zareh, Khoren and Ghevont is a separatist act and must be condemned by the whole community.[6]

Catholicos Khoren with Lebanese President Camille Chamoun and the US ambassador

As a result, many Armenian Apostolic churches in Lebanon, Syria, the USA and other countries pledged allegiance and declared loyalty to Etchmiadzin.

On the other hand, Aztag described the election as a “democratic and popular” process and published congratulation letters sent to Catholicos Zareh. The newspaper also published photos of the Lebanese President, officials, Arab and foreign ambassadors and diplomats who met with the Catholicos in order to give local, regional and international legitimacy to the election.[7]

The opposition accused the church of turning its face away from the people. Zartonk claimed the clergy did not serve God, and that they followed selfish interests. The church was corrupt[8] and Antelias had been turned into a “Tashnag militia stronghold”.[9] The opposition went even further and declared that archbishop Khoren and the Tashnags were “kicking” out the priests who had devoted their lives to the church and replacing them with pro-Tashnags. The newspaper reported that the church had been de-institutionalized and monopolized by some “selfish archbishops.”[10] Aztag refuted these accusations, and commented that those who rebelled against the church should have no role in the church and warned of the “communist takeover of the church.”

Intra-Armenian Violence

In 1958 Lebanon experienced a civil war. For the first time in the post-independence period the identity and structure of the state were shaken. The pan-Arabist adherents of Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose ties with the Soviet Union alarmed the West, were engulfing the Middle East, and Lebanon’s Sunni Muslims wanted to join the new United Arab Republic formed by Egypt and Syria (1958). Civil unrest, fuelled by explosive claims that Chamoun aimed to change the constitution to extend his presidential term, spread as an opposition that cut across sectarian divisions clashed with loyalist forces.[11] Christian, especially Maronite, reaction to the increased intensity of Arab nationalism was also vehement. Several factors seemed to pose a threat to Lebanon’s independence and, consequently, to non-Muslim minorities. These were the symbolic rise of Abdel Nasser, the trend of Muslim opinion toward Arab unity, and the demands by the Muslims for equality of sectarian representation in the Lebanese public sector and even calls for abolishing political sectarianism by Lebanese leftists.[12] This exacerbated sitiuation pushed President Chamoun to call for US military aid. In July 1958 US marines landed in Lebanon under the Eisenhower doctrine.[13]

The year 1958 was the peak of political violence for the Lebanese-Armenian community and turned into extensive killings. Already the world was divided between the Western and Communist camps. The Lebanese-Armenian community, too, was politically divided on both the regional and local levels. The Tashnags were regionally in the anti-Communist camp and allied locally with the Lebanese President, Chamoun, who was also anti-Communist, while the Hunchags and Ramgavars were supportive of the Communist camp and opposed the Lebanese government.

According to Ararad[14], the 1958 conflict was a “popular revolution against a corrupt state”.[15] It reported the crisis as follows:

The current struggle is not a religious struggle; it is not about Christians and Muslims killing each other; it is about fighting against injustice, corruption and oligarchy. The people should stand together and continue their fight. What more will we lose? Already we have lost what we can; now it is time to stand up and fight again and take our rights. Our fight is just and popular, and we will win.[16]

Ararad reported that police barracks were being taken over by “popular militias” in Tripoli and Beirut.[17] The newspaper also reported the position of the Soviet Union regarding the Lebanese political crisis: “The Soviet Union will not remain silent and will help Lebanon to continue its fight against the imperialists and American agents.”[18]

Another report in Ararad claimed that the opposition would continue the fight with the backing of the Arab people. Obviously, Ararad viewed the events from an ideological perspective and defined the Lebanese conflict as a rebellion or a popular uprising against imperialism and corruption. Zartonk shared the Ararad perspective on both the regional and local levels. On the other hand, Aztag disagreed with both. Aztag showed its “anti-Communist” perspective, though it did not glorify the pro-Western camp. On the regional level Aztag reported events and provided information about the disagreements and conflicts between Nasser and Communism. It reported how Nasser cleansed the Syrian army of Communists.[19] Furthermore, the newspaper blamed the Communists for the incidents that took place in Lebanon and fully supported the policies and the actions of the state and the president.[20] It should be noted that the Tashnag leadership was taking clever, politically calculated steps by criticizing the Communists and differentiating between the Communist camp and the pan-Arab Nasserist camp unlike Ararad and Zartonk. Thus, Aztag distanced itself from accusations of being a “pro-western” political puppet.

The editorials of the three Armenian dailes clearly reflect the extent of their hatred and animosity, which eventually were transformed into intra-communal assassinations. I will provide some examples of how these newspapers reported the incidents and accused each other of being “agents” and “conspirators.”

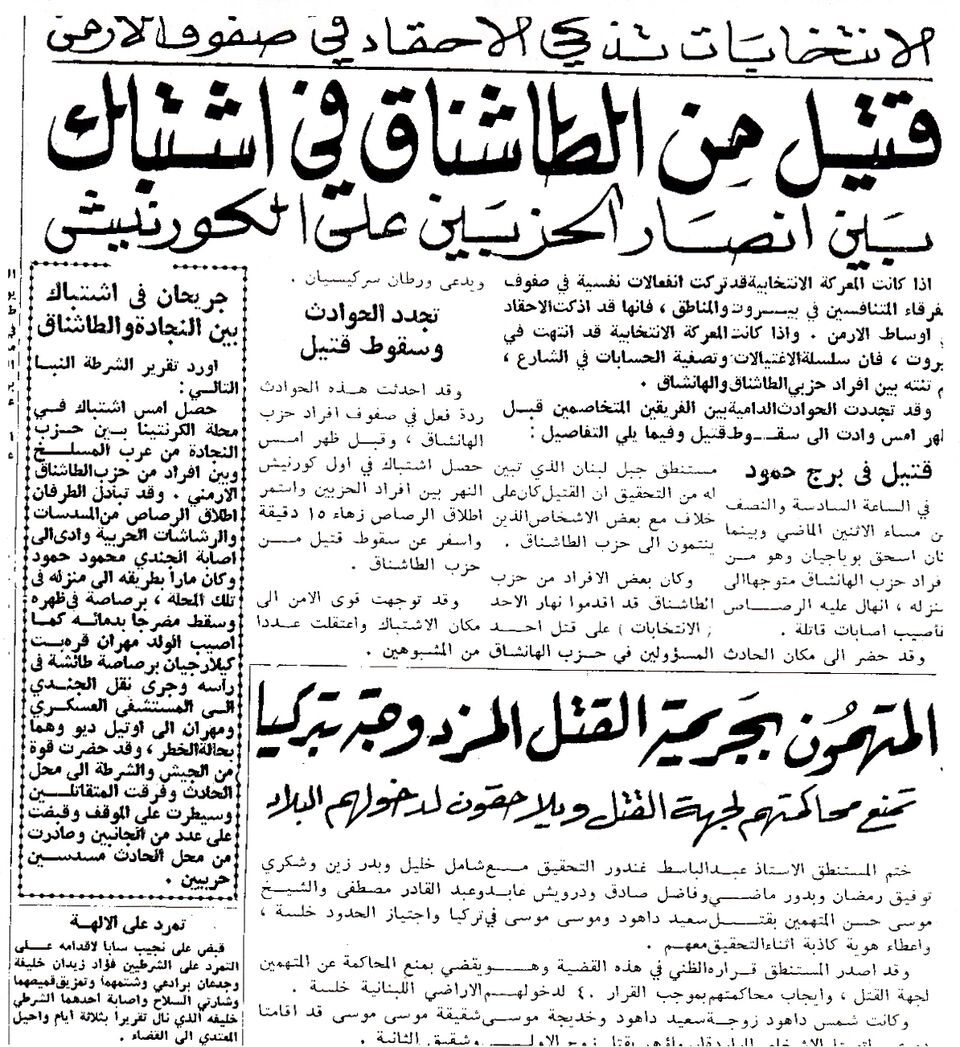

Lebanese daily, al-Nahar newspaper reporting the inter-communal Armenian clashes in Beirut

Ararad reported the assassination of a Hunchag partisan, Vartivar Khatchadurian, and accused the Tashnags of his assassination. According to the report, Vartivar was a victim of “Tashnag conspiring bullets.”[21] The report said: “He survived the Turkish bullets during the Hadjin rebellion, but he never thought that his life was to be taken by a Tashnag traitor who has lived in the Hadjin neighborhood (Beirut).” Ararad saw these assassinations within the Lebanese context and continued: “He was martyred for the freedom of Lebanon and due to current conflict in the country.”[22] Zartonk launched fierce attacks on the government stating that the “police clashed with the locals instead of detaining the murderers.”

Aztag, on the other hand, published an article titled “How did they kill the traitors?” Its unknown author indirectly justified the killing of Arshavir Yessayan and Garabed of Zeitun, two Hunchag “spies”, in Aleppo in 1958.[23] Interestingly, this story was published after the assassination of Vartivar. Moreover, Aztag reported the assassination of one of the Tashangs as follows: “The Communist Hunchags killed a 65- year-old comrade, Simon Hagopian; the army surrounded Hadjin; the same criminals threw a bomb in Karm el Zeitun area [Beirut]; the army and security forces will stop them and capture these criminals.”[24] Aztag labeled the Hunchags as “Communists,” thus throwing the responsibility for the assassinations on “Communist agents” and asserting that the state would detain the criminals.

Interestingly, though the Lebanese civil war ended on October 25, Armenians continued street fighting, assassinations and fratricide. Eventually, the state interfered, and the minister of Interior Affairs, Raymond Edde, held meetings with the Bourj Hammoud Municipality and representatives of the Armenian political parties to establish a ceasefire and warned that otherwise the state would take action and interfer. The Armenian political parties did not have any interest in challenging the Lebanese state and its army; thus, they declared a truce though some clashes continued. Aztag reported the truce as follows: “In a few hours we will throw away our old clothes and wear new ones; it is time for each of us to isolate ourselves and contemplate.”[25]

The Armenian “Third Force”

The Rise of the Voice of the Independents

Given extremism, clashes of interest and the uncompromising positions of Armenian political parties, it was necessary to pave the way for a third track in the Lebanese Armenian community. Unlike other communities, the Armenian community was highly politicized and divided into two camps due to the prevailing circumstances. Therefore, this initiative faced challenges and obstacles. In this part, I will analyze the position regarding the formation of an “independent movement”, the church crisis, relations with the fatherland, and the inter-communal clashes as well as discuss the failures and the success of this track.

A USMC M48A1 on Lebanese shores north of Beirut, Antelias area.

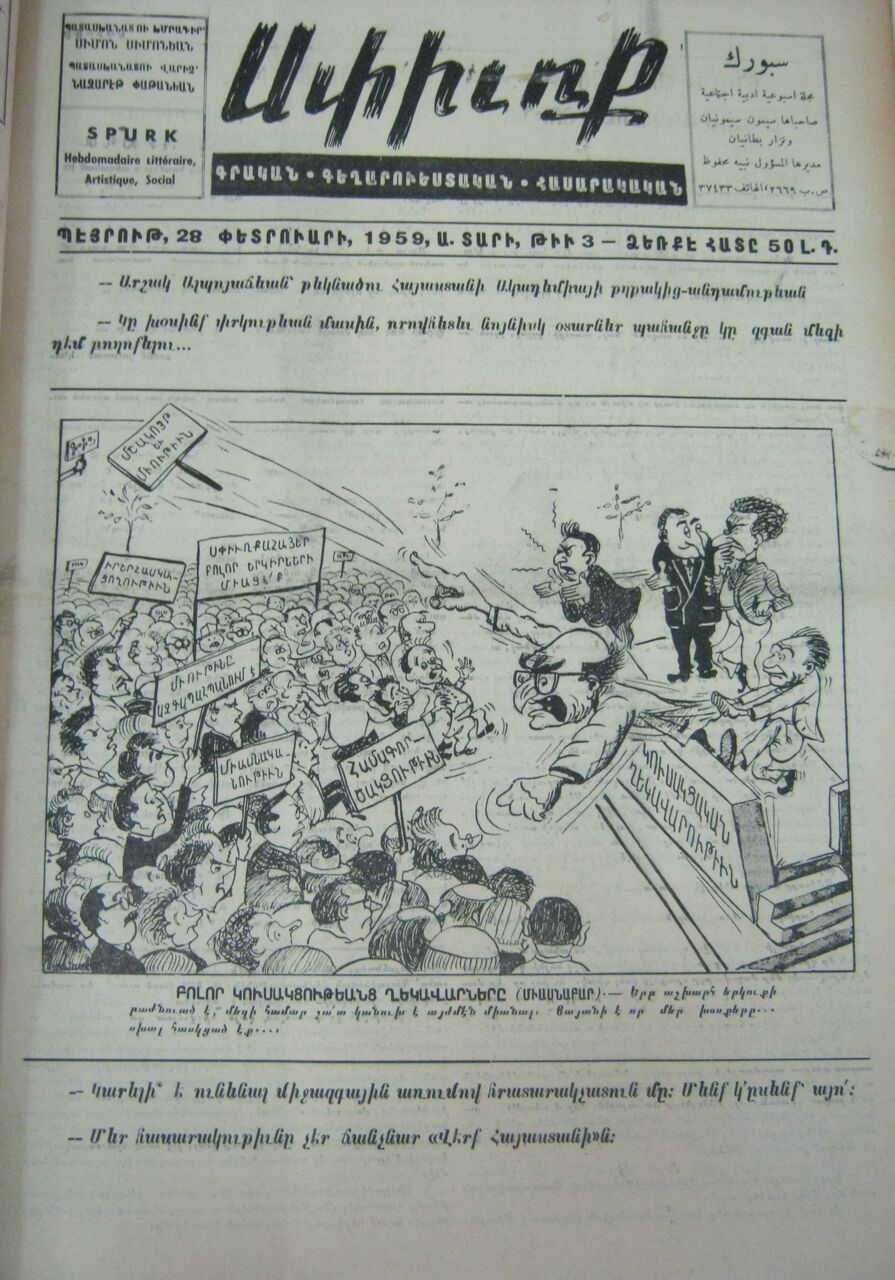

During this period (1956-1960) few ‘independent’ Armenian newspapers came into the arena to raise the concern of Lebanese Armenians regarding the intra-communal violence and church crisis. Some of these newspapers, though officially non-partisan, were affiliated with political parties, unlike Spurk (Diaspora), an independent, critical newspaper founded and launched by Simon Simonian in 1958.[26]

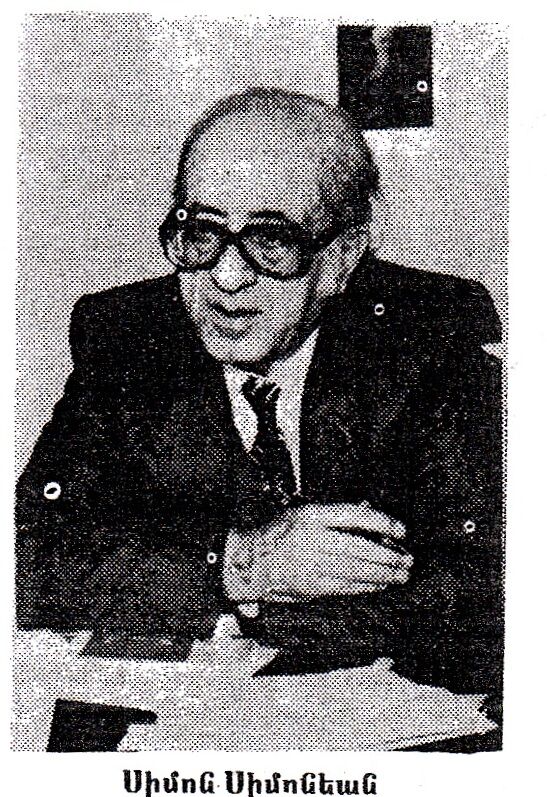

Simonian, a nationalist Armenian and a non-partisan, was born in 1914. He had held

Simon Simonian

a teaching position in the Antelias Catholicosate Seminary. He also had good connections and family relations with many officials from different Armenian political parties and clerics; he was a friend of Catholicos Zareh from the Seminary years and also loyal to the See of Etchmiadzin.[27]

Simonian’s visit to Soviet Armenia in 1954 had a great impact on him. He realized that, in addition to many positive changes, there were many negative facts in Soviet Armenia; the country was not a “paradise” as was claimed in the Diaspora by “pro-Soviet” Armenian newspapers. Thus he wanted to speak out the truth, and on 4 April 1958 he published the first edition of Spurk weekly with the following motto: “With all, against all, but always with and for the Armenian People.”[28] The weekly stopped shortly afterwards due to the civil war of 1958 and resumed on 14 February 1959 with an editorial entitled “Our Position”.[29] The editorial stated that the newspaper was “independent but not neutral” and continued: “We are not indifferent to what is happening around us, we have our own views and will raise them… Our demands are clear… our loyalty is to the Armenian people, their existence as a single body is far more important than the interest of the political parties. The newspaper will be the Armenian people’s newspaper.”[30] Spurk aimed to raise the voice of the independents and warn the Armenian public about the “catastrophe” that was being brought on the community by the conventional Armenian political parties and their leadership.[31]

Collaboration with the Veradznunt Association

From 1960-1961, Spurk collaborated with the Lebanese Armenian Veradznunt (Renaissance) Association.[32] The Association, founded between 1945-1947 by Pakarad Bakalian, was an independent cultural organization, active in Armenian politics that established relations with local Lebanese politicians as it intended a “rapprochement” of Armenian and Arab cultures. It ran a club in Beirut, a sports organization called Sevan, and an Armenian choir.[33]

In order to reaffirm their cooperation, both sides made a joint declaration which was published in Spurk:

The current situation in our community pushed the Lebanese Veradznunt movement and the Spurk weekly to cooperate and build a new path. This initiative springs from national and communal interests; both sides will face many challenges and put the interest of their community above selfish political interests.

As a non-partisan independent cultural organization, Veradznunt has served the Lebanese Armenian community in many ways and is loyal to the Lebanese state and its institutions. Furthermore, we want to cooperate and build bridges with all Lebanese sects without any discrimination, and based on mutual understanding and respecting diversity. We also want to protect the interests of our community in governmental institutions.

On the national level, Veradznunt invested a lot in the cause of repatriation to Armenia, in 1946 and 1947 following the years of World War II. We supported this cause both financially and morally based on our ideology that Armenians in the Diaspora are an integral part of our fatherland.

On the communal scene Veradznunt has built relations with all Armenian political parties based on mutual respect, honest brotherhood and national determination. We have not taken sides with one against the other. We are against a political or leadership monopoly.

Concerning the Cilician Catholicosate crisis, the Veradznunt movement does not support any person over another; our main concern is the unity of our community and the role of the church in safeguarding our nation. We are against the interference of politics in the church and vise versa. We support the unity of the Armenian Apostolic Church under the guardianship of the Catholicosate of all Armenians (Etchmiadzin).

Spurk weekly, with a few dedicated intellectuals, has aimed at finding a third way within our community and introducing our cultural and ideological goals to readers. From this perspective Veradznunt has agreed to work and cooperate with Spurk weekly, due to our common vision.[34]

The declaration underlined that the similarity of views between Veradznunt and Spurk would bring a new spirit to Lebanese-Armenian cultural and national life. Both would work like one soul for the interest of the community. But on the other hand, reality did not reflect the spirit of the declarations. In 1960, a member of Veradznunt movement, Pakarad Bakalian, was included in the list of the Hunchag-Ramgavar alliance in Beirut against the Tashnag-Phalanges alliance in parliamentary elections. Moreover, although the movement tried to distance itself from the Armenian “pro-Soviet” camp and play the card of neutrality, on many occasions it opposed the Tashnag view regarding the church crisis.

Thus, based on the above-mentioned press release, both Spurk and Veradznunt and the independents had four targets: a) to bring forth a new “third independent voice” within the community, b) to resolve the church crisis, c) to strengthen relations with the fatherland and d) to put an end to the tensions in Armenian circles.

The Formation of the “Third Force”

Through its editorials, Spurk suggested the establishment of a “third force”, which would be composed of independent newspapers, individuals, and organizations. It also stressed the need for independent media that would only serve the interests of the people.

First, it identified the problems that hindered the activity of independents:

- Closed-minded and extremist political thinking.

- This thinking will wither away only when the vast majority of our community, which is composed of independents, realize that they also have power; thus they will build a strong force.

- People who are outside the influence of political parties such as doctors, businessmen, engineers, self-employers, should face the reality that they can and have the ability to bring change and progress to our community. Hence, in addition to their financial capabilities they will invest in national and political causes.[35]

Spurk argued that one of the obstacles independents faced in the Diaspora, was that political parties, which were somewhat organized, were able to control and manipulate the disorganized independents. These independents were not able to play a leading role since they were marginalized and disorganized.[36] Spurk proposed the establishment of strong independent media that would raise the concerns of the people and serve the overall interests of the community.[37] In its editorials Spurk repeatedly asserted the establishment of a pan-Armenian “central committee” to unite all independent organizations and media in and outside Lebanon.

Suggestions to Resolve the Crisis Over the Church

The resolution of the church crisis was one of the central concerns of Spurk and other independents. They criticized the interference of “dirty politics” in religion and suggested ways to overcome this problem in a manner that would “satisfy both sides.”

Spurk claimed it was difficult to limit the role of the Armenian Apostolic Church to merely the religious sphere, since the Church also had a national and historical role in Armenian communal life. Armenian community life was directly impacted by the events taking place in the Cilician church. Since their positions were polarized, both sides were unable to reach a compromise. Thus, the church should retake its national role in the community and navigate out of politics.[38]

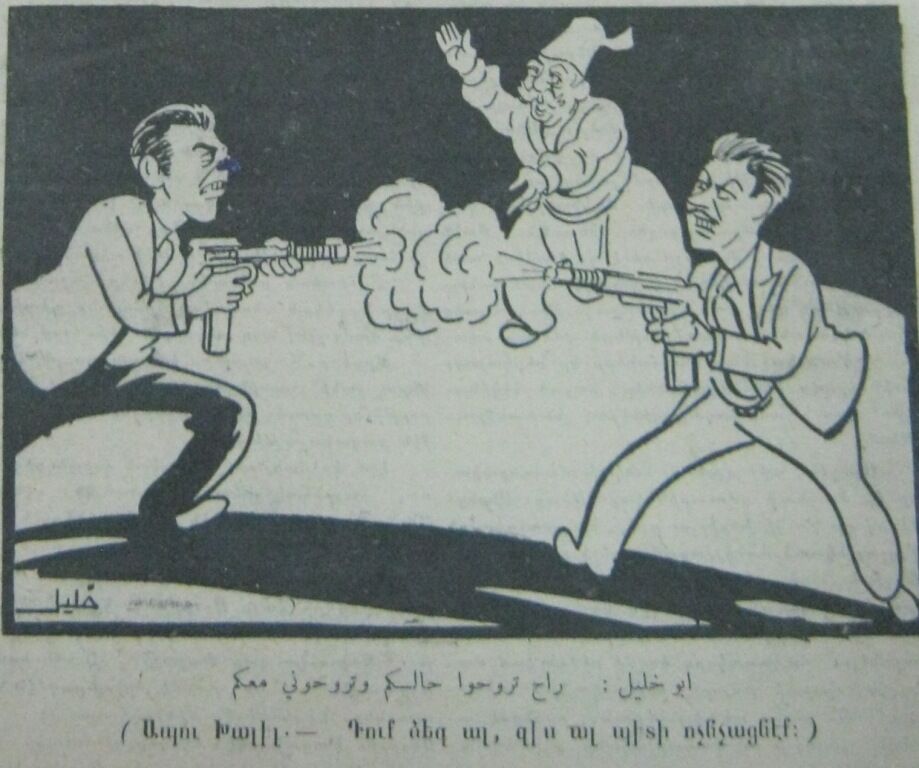

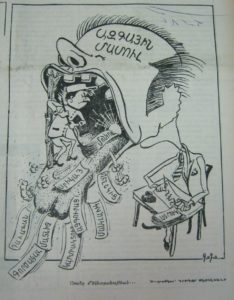

Cartoon, Spurk weekly “National media”

Hence, Spurk gave three explanations and suggestions in order to resolve this crisis:

1- It is easy to find solutions since all parties recognize the existence of the problem. It will be a mistake to forget the problem and shut the door. Thus, after recognizing the problem, it is easy to find solutions.

2- After recognizing the problem, we should go to the roots of the conflict and try to find a suitable solution for all. The church must play its historical role in our community. For this we should gather around the church, and the latter must welcome us. We must be honest with each other and be able to communicate. Currently when world powers disagree, they do not go to war, they sit with each other and negotiate till a solution is reached and both sides are satisfied. As long as we are ready to listen to each other, there will be solutions. As a solution we propose a “summit meeting” between the Armenian Catholicos Vazken and the head of the Antelias church to reach a compromise. The two sides must express their willingness and readiness to negotiate, since the current conflict needs a solution from the church and within the church and not by outside parties or political groups. For centuries the church has played a political role in preserving national identity and reflecting the will of the people. Now the church canot limit its role by supporting the will of one group and marginalizing the will of others. Our national church belongs to the nation and should not be affiliated with a certain ideology or political party. On the other hand, it is the duty of political parties to respect the historical role of our church and keep it out of politics.

3- We will cooperate with those who are eager to reach a solution and preserve the unity of our nation and its institutions. We are informed that even Lebanese groups are working to bring both ideas together and end this crisis.[39]

Cartoon, Spurk weekly “National manipulation”

Relations with the Fatherland

Spurk claimed it was important to strengthen relations with the fatherland, since it was through the fatherland that we would preserve our cultural identity, no matter what kind of regime was installed there. That was why a cultural bridge should be established and our youth encouraged to participate in the cultural renaissance that Armenia was having. The power of the fatherland depended on the support and love of our youth in the Diaspora. This power was not limited by borders or territory. The fatherland was essential for security. Thus we should not abandon our fatherland regardless of our ideologies.

Spurk proposed three tracks to develop this bridge:

- To have a cultural link and share our heritage with each other.

- This bridge should not have any political agenda. The Soviet Armenian authorities should not use this bridge as a tool to interfere in our political affairs and engage in diplomatic relations with our local governments via our communities.

- Invite artists and musicians from the fatherland to the Diaspora and vice versa.[40]

Intra-Communal Violence

Spurk was very critical of the political parties and their leadership regarding intra-communal violence and accused them of “blindness”, “ignorance” and “selfishness.”

Under a title of “Hit Hadjin, hit Bourj Hammoud” the editorial launched a strong attack on the Armenian political parties. It stated:

We thought that as the Lebanese conflict [the 1958 civil war] had finished, there would be no mourning in any Armenian family. We were wrong and so naive. Once again Armenian blood bleeds. Why? What was the reason? Is a football match between two Armenian clubs worth killing each other for?

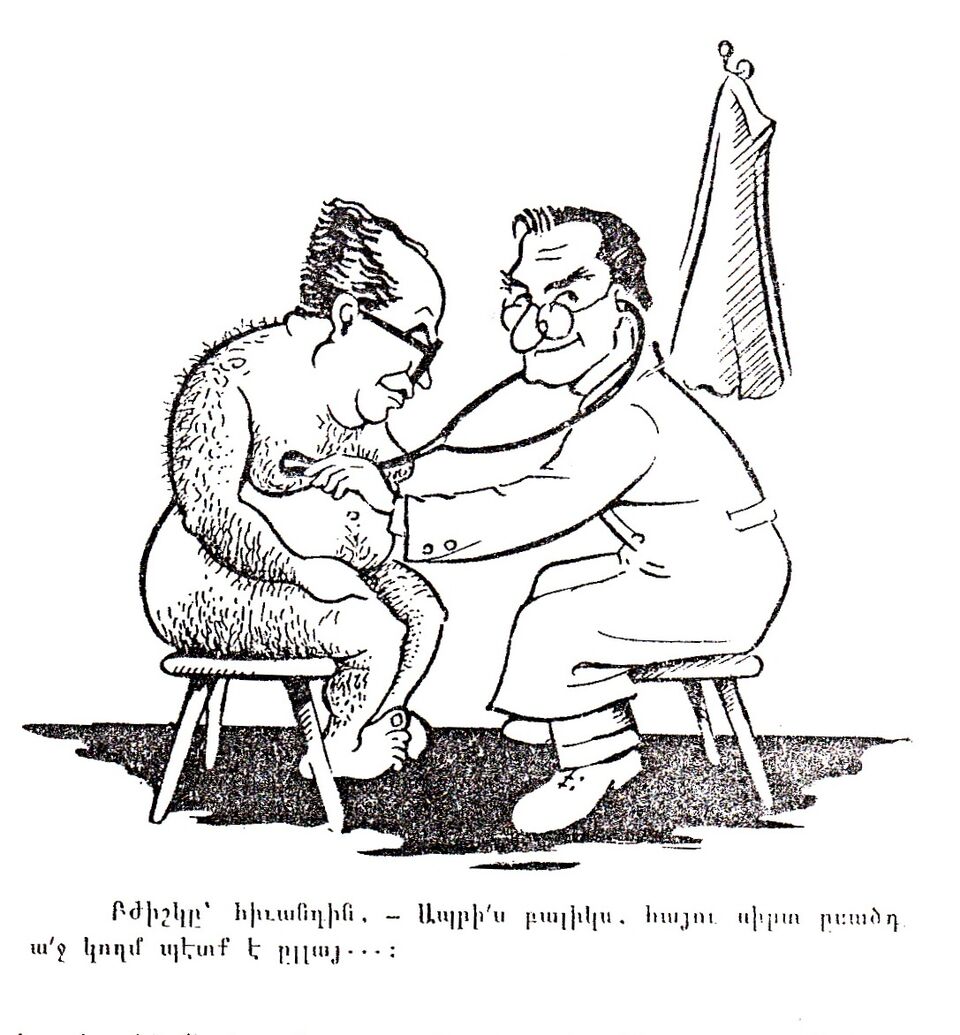

Cartoon, Spurk weekly,”Excellent my child, the heart of an Armenian is always located on the right.”

The editorial went further and attacked the street gangs that were supported, backed and protected by the parties and said:

Once again borders were drawn between two Armenian neighborhoods, armed people [are] all over the streets…why? Simply because our political party leaders wanted it that way, because our street “za’ims”[41] wanted it. They have formed a generation that is based on hatred. They have formed a generation which worships gun. And now the “za’ims” lead this madness because our parties are unable to control them; they have no power on the streets to control these gangs or the street “zai’ms”.

In order to overcome this catastrophe the editorial suggests: a) the parties must put an end to this “madness”, b) solve the issue of these “zai’ms” and “clean them from the streets”, confiscate their weapons and put them under party discipline or to take any “necessary steps” to stop them. The editorial ends with the following words: “We used to commemorate April 24 once a year, now we are commemorating it multiple times.”[42]

Finally, Spurk translated the article of Sa’id Freiha[43], who criticized the Armenian leadership and asked:

Till when will you continue killing each other? Ttill when will you continue murdering and slaughtering each other? Take a lesson from us; we killed each other too, but we stopped… Let it be clear that what is happening in the Armenian quarters is not only dangerous to Armenians but also threatens the security of the Lebanese state.[44]

Assessment and Conclusion

Within this turmoil one can hardly draw clear-cut conclusions concerning the short-term objectives and achievements of the “Third Force.” In the long run, however, one may discern that the goals of Spurk and other independents failed in several respects: a) The independents failed to come together, combine their efforts and organize a strong, balancing force, a middle ground that could deter both sides and force them to compromise, b) They failed to insulate themselves from the two camps since some of the independents were inclined to one side or the other. These individuals were affiliated with political parties and lacked regional or local backing, c) To various extents, both camps had infiltrated this group. That is why in 1960 Veradznunt had a candidate on the Hunchag-Ramgavar list in Beirut against the Tashnag-Phalanges alliance, d) Though the independents kept their “independence”, due to the Lebanese sectarian electoral system, they could not build strong alliances with non-Armenian independents. Indeed, they failed to translate their relationship with non-Armenian independents into an adequate political alliance, e) In addition, some wealthy independent Armenians failed to invest adequately in this track, foster a cohesive community and a front against the conventional Armenian parties and their leadership.

The “third track” partly achieved its goal of improving relations with Soviet Armenia. A number of Soviet Armenian cultural figures, even sports teams, were invited to Lebanon as of the late-1950s. However, this was not reciprocated by visits of Diaspora cultural figures to Soviet Armenia.

“New Hope” Truce, Aztag, 1958

As for the Church crisis, in 1965 the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide was commemorated at a pan-Armenian level, and later the traditional political parties gathered around the church. Finally, after 1960 the intra-communal clashes almost ceased. Moreover, during the Lebanese Civil War, which started in 1975, positive neutrality was declared by the community leaders and united Armenian self-defense units were formed to protect Armenian neighborhoods against “outside” attacks.

Thus, though disorganized, the Armenian third force succeeded in many missions and brought new ideas to the polarized Lebanese-Armenian arena. Moreover, the Armenian third track may have served as an example to other politicized communities which experience deep political and ideological divisions.

The research paper is originally published in Armenians in Lebanon part II book (Haigazian University Press-2017)

Yeghia Tashjian is currently pursuing his graduate studies in Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut. He has graduated from Haigazian University in political science. He is a Lebanese-Armenian political activist, researcher, and blogger. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a research assistant at Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the regional officer of Women in War a gender-based think tank.

ENDNOTES

[1] Simon Simonian’s photo is taken from his archives.

[2] Ramgavar (Armenian Liberal-Democratic Party) Party’s official organ in Lebanon.

[3] Tashnag (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) Party’s official organ in Lebanon.

[4] Aztag, 20 March 1958, p. 1.

[5] Zartonk, 28 July 1956, p. 2.

[6] Zartonk, 9 September 1956, p. 1.

[7] Aztag, 22-23 February 1956, p. 1.

[8] Zartonk, 11 July 1956, p. 1.

[9] Zartonk, 13 July 1956, p, 1.

[10] Zartonk, 31 July 1956, p. 1.

[11] Alasdair Soussi, Legacy of US’ 1958 Lebanon invasion, 15 July 2013, Al Jazeera, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/07/201371411160525538.html , accessed 6/3/2016.

[12] Karol R. Sorby, Lebanon: The Crisis of 1958, Institute of Oriental and African Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia, 2000, p. 92.

[13] U.S. foreign policy pronouncement by President Dwight D. Eisenhower promising military or economic aid to any Middle Eastern country needing help in resisting communist aggression.

[14] Hunchag (Armenian Social-Democratic Hunchagian Party) Party’s official organ in Lebanon.

[15] Ararad, “The Lebanese People Demand their Rights,” 15 May 1958, p. 1.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ararad, 27 May 1958, p. 1.

[18] Ararad, 15 June 1958 p. 1.

[19] Aztag, 7 April 1958, p. 3.

[20] Aztag, 7 April 1958, p. 3.

[21] Ararad, 22 May 1958, p. 3.

[22] Ararad, 22 May 1958, p. 3.

[23] Aztag, 4 December 1958, p. 2

[24] Ibid.

[25] Aztag, 1 January 1959.

[26] Haigazian University, The 500th Anniversary of Armenian Printing, [2012], [p. 8].

[27] Personal interview with Sassoun Simonian, 7 May 2014, Simon Simonian’s son.

[28] «Ամենուն Հետ Եւ Ամենուն Դէմ, Բայց Մի՛շտ Եւ Մի՛միայն Հայութեան Համար» Spurk, “A Talk about our Path”, 4 April 1958, p. 1; “The April 24 for the second time: A.- An Introduction and a Word to our Friends,” Spurk, 1st year, # 5, 4 May, 1958.

[29] The Spurk weekly was run by Simon Sinomian from 1958-1974.

[30] “Our Position”, Spurk, 21 February 1959, p. 1. The editorial was written by Nazaret Patanian.

[31] It is quite surprising and inspiring that Simon Simonian took the initiative on his own to raise the voice of the “third force”. A voice that was marginalized by partisan forces shaping the events within the Lebanese-Armenian community. Simonian criticized all sides and was criticized from all sides. In his editorial “Hit Hadjen, hit Bourj Hammoud”, he called upon the political parties to “cleanse” the “street thugs,” a daring statement in those risky days. While Armenian partisan newspapers were busy accusing each other with treason, Simonian reminded the political elites that they were shifting from their main national target, the “Armenian cause”. In his editorials, he clearly stated his vision to create an independent force. It is hard to approve whether this force was to be an organization replacing the traditional parties or it was just theoretical. Nonetheless, he succeeded in breaking the wall of silence for a period of time.

[32] Zaven Messerlian, Armenian Participation in the Lebanese Legislative Elections 1934-2009, Beirut, Haigazian University Press, 2014, p. 39.

[33] Messerlian, p. 38.

[34] “Joint Announcement”, Spurk, 16 January 1960, p. 1.

[35] “The Birth of the Third Force”, Spurk, 27 August 1960, p. 1.

[36] “The Duty of Non-Partisans”, Spurk, 20 August 1960, p. 1.

[37] “The Role of Independent Media”, Spurk, 3 September 1960 p. 1.

[38] “Difficulties of the Church,” Spurk, 17 September 1960, pp. 1, 6.

[39] “Our Position towards the Church”, Spurk, 14 May 1960, pp. 1, 2.

[40] “Relations between Diaspora and Fatherland,” Spurk, 27 February 1960, p. 1.

[41] Gang leaders.

[42] “Hit Hadjin, Hit Bourj Hammoud”, Spurk, 5 March 1960, p. 1.

[43] Freiha was the founder of the Lebanese al-Anwar daily and a renowned journalist. The article was published in the Lebanese al-Sayyad daily on 14/7/1960.

[44] Sa’id Freiha, “To Our Armenian Brothers”, Spurk, 23 July 1960, p. 1.