Introduction

The Armenians were one of the millets of the Ottoman Empire. Identifying their exact number is difficult, but according to records from the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there were approximately 3,000,000 Armenians living within the Empire in 1872.[1]By the end of the eighteenth century around 250,000 of them lived in Istanbul.[2] They were governed by a group of high profile men known as the amiras, who seized power during the eighteenth century. In this paper, I will point out to the definition of the term amira, the rise of this class, and the privileges enjoyed by its members. In the course of my writing, I will delve into the dual role played by this elite within the Ottoman state and the Armenian millet. Then, I will highlight the causes that led to the eventual decline of this class during the nineteenth century.

Definition of the term “Amira”

To begin with, the term amira originates from the word “emir” in Arabic, which means being a chief or a commander.[3] Armenians bestowed this honorific title to their fellow Armenians in order to denote their nobility.[4] “Amira” was not a word officially recognized by the Ottoman authorities.[5] Moreover, obtaining such a title was quite difficult. Being wealthy and having well-established relations with Ottoman officials were required for reserving an admission ticket to this class.[6] Hence, it consisted of people belonging to the upper echelons of the Armenian millet, who also held positions within the Ottoman state institutions.[7]

Rise of the Ottoman Armenian Amira Class and their Origins

In the course of the seventeenth century, prior to the use of the amira title, wealthy Ottoman Armenians were given the titles of hoca and celebi.[8] These people similar to their successors held important posts within their communities and the Ottoman circles. They controlled much of the Ottoman financial affairs, and at the same time governed the Armenian millet.[9]

Starting from the eighteenth century, the above mentioned titles were replaced by amira.[10] As Barsoumian has noted that it was an “honorific [title] which takes wealth, court position and status into account.”[11] Moreover, the title of amira was used exclusively for the affluent Armenian Orthodox men, and not to the Armenian Catholics, who were referred as celebis.[12] Hence, not all people had the chance of joining the ranks of the amira class. The majority of amiras originally came from the Ottoman city of Agn (Egin in Turkish).[13] But, there were others who had moved to the Ottoman capital from the cities of Van, Sivas, Kayseri, and Divrigi. [14]

The Privileges of the Amiras

The amiras constituted a minority within the Armenian minority. Various sources give different estimates regarding their number, ranging between 100 and 200 men.[15] They all lived in Istanbul, mainly being concentrated in the quarters of Ortakoy and Haskoy.[16] They enjoyed a wide range of privileges because of their great economic power and influence over the Ottoman imperial circles.[17] First, the Armenian amiras had their own way of dressing. They wore a fur coat and put a turban on their heads similar to Turkish statesmen. Hence, they were distinguished from the ordinary Armenian people. They were not part of the regular dhimmi subjects.[18] Second, the amiras were allowed to ride horses,[19] which was then a prohibited practice for non-Muslims due to the Pact of Umar. Third, the amiras lived a luxurious life. They owned houses similar to palaces.[20] They had their own staff such as scribes, priests, and more, who facilitated their lives.[21]

Garabed Amira Balian

Armenian Amiras and the Ottoman State

In general, the amiras had close ties with the Ottoman state officials. Some of them were sarrafs (bankers), others were architects and there were some who were merchants or worked in the industrial sector.

The Armenian sarraf-amiras, similar to their counterparts, played a crucial role in tax-farming. The majority of them were from Agn, and possessed riches due to their participation in trade expeditions to Anatolia and Istanbul. [22] The sarrafs paid the actual amounts of the iltizam to the imperial treasury. Most of the prospective multazims sought to guarantee their support to take hold of an iltizam.[23] In their turn, the sarrafs wanted to maximize the rate of their profits. They acted as sarrafs and merchants simultaneously. Appointing their agents in the Ottoman provinces allowed the sarrafs to pay a closer attention to the financial affairs of the iltizam. Converting taxes received in kind into cash was another method employed to guarantee profits. [24] The sarrafs were also perceived as the only hope of financially weak Turkish individuals inspiring to hold high governmental posts.[25] After providing assistance, the sarraf-amiras made lifetime acquaintances with the Turkish pashas. [26] Hence, they gained more power and influence.

Meanwhile, some other amiras were merchants who supplemented the Ottoman Palace and the army with its needs. These men were known as bazirgans.[27] Among them Garabed Amira Manougian controlled the shipping routes between Istanbul and Russia.[28] In addition to the sarrafs and merchants, the amira class was also rich in architects. The two prominent families in this field were the Balians and the Serverians. Garabed Amira Balian was the Chief Imperial Architect. He received around five thousand Ottoman gold coins every time he completed the construction of a building.[29] In general, the Balians were well-known architects who designed a large number of mosques, palaces, factories, and public buildings.[30]

Other important jobs were held by the Duzians and the Dadians. The former were involved in the Ottoman economic sector. They controlled the imperial mint from 1758 till 1880.[31] The Dadians acted as agents of modernization when a huge economic and industrial gap existed between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. Establishing military factories were one of the first steps towards catching up with modern Europe. [32]

The Dadians administered two gunpowder factories.[33] Dad Arakel, one of the main pillars of the Dadian family, established a gunpowder factory in 1795. He was also appointed as the chief gunpowder producer in the Azadli factory.[34] Later on, his legacy was kept alive by his descendants Hovhannes and Boghos Dadians, who founded an iron and steel factory in Zeytinburnu in 1844. Westerners called this establishment as the “Grande Fabrique” since, it provided the required commodities such as “pumps, small machines, steam engines, swords….” to the Ottoman military.[35]

In his turn, Hovhannes Amira Dadian was one of the favorites of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II. He got famous after having created a new machine that received the Sultan’s deep appreciation.[36] On several occasions, Hovhannes Amira travelled on his behalf to Europe, to introduce new methods of production to the Ottoman factories, which suffered from lack of modern European machines.[37] This amira founded a technical school to prepare well-skilled staff for the above mentioned iron and steel factories.[38] Moreover, during his stay in Europe, he also learned new weaving and gun-making techniques, which he introduced to the Empire.[39] In 1836, a wool clothing factory was established in the Ottoman city of Sliven (currently in Bulgaria) by Hovhannes Dadian.[40] Similarly, he along with Boghos Dadian built a broadcloth factory in Izmit in 1842. Another similar foundry existed in Hereke, established in 1843 by these two men. However, it was later converted to a silk factory having machines imported from Austria.[41] Taking these events into consideration, one clearly understands the important role played by the Armenian amiras of different professions in guiding the Empire towards progress.

Armenian Amiras and the Armenian Millet

Controlling the life of the Armenian millet was another crucial role played by the amiras. They exercised great power over the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, which was the main institution governing the lives of the Ottoman Armenians.[42] The amiras had the power to nominate their own patriarchal candidates or dismiss them.[43] This trend continued until the year 1846.[44] They acted as such due to their coverage of the Church’s expenses.[45] Furthermore, the amiras were also members of the Patriarchal Advisory Committee established in 1834, with the aim of helping the Patriarch manage the various educational and medical institutions operating under its auspices.[46]

The amiras desired to gain the support of the low status Armenians. One of the ways to achieve this, was through improving the services sector. They made generous donations. Worthy of mention is Harutyun Amira Bezdjian’s 100,000 piaster donation to the poor in 1829.[47] Moreover, the amiras took the initiative to build a hospital and a network of schools. The Saint Savior Hospital of Istanbul is still functioning and serving the community. It came into existence in 1834 through the joint efforts of the amiras.[48]

Some amiras showed great concern towards educating promising Armenian youth. A large number of schools were established by them starting from the eighteenth century. Thus, through their efforts to raise the literacy level, the amiras gained increased popularity among the people. The first Armenian secular school opened its doors in Kum Kapu in 1790 through the financial support of Megerditch Amira Mirijanian.[49] Two other schools were also opened by the same amira in the regions of Langa and Balat.[50] In addition to these educational institutions, Hovhnes Amira Dadian built a school in Azadli giving it his family name.[51] Amiras Mgrditch Djezayirlian and Harutiun Nevruzian also followed in the footsteps of the other amiras by establishing a school called the St. Nersisian for boys and girls at Haskoy in the year 1836.[52] Moreover, Amira Djezayirlian paid for the tuitions of promising Armenian students to continue their higher education in European institutions.[53] It is noteworthy that by 1847 twenty-four Armenian elementary educational institutions were operating in Istanbul thanks to the amiras’ support. This number was reached forty-two in the year 1857.[54]

Another way of increasing the number of literate Armenians was through founding printing presses. One of them was established by Shnorhk Amira Miridjanian in the neighborhood of St Mary Church at Kum Kapu.[55] Moreover, benefitting from their ties with the Ottoman state officials, the amiras were influential in averting the state decisions regarding the prohibition of the construction of churches.[56] For instance, Selbos Amira was able to build several Armenian churches.[57] Thus, the amiras played an enormous role within the life of the Ottoman Armenian community that would not have been educated without their backing.

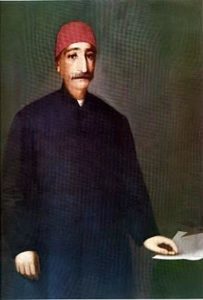

Hovhaness Amira Dadian

Decline of the Amira Class

The power of the amiras began to decline during the second half of the nineteenth century for several reasons. First, on the eve of the Tanzimat, the Armenian sarraf-amiras, similar to any other Ottoman sarraf, received a major blow due to the abolishment of the tax-farming as a result of the Gulhane Rescript of 1839.[58] Although, this method of taxing was later called back to life, however, they were not able to recover quickly and did not have the same power as they used to enjoy before. Their condition worsened after the Crimean war of 1853-1856, when the Europeans penetrated into the Ottoman economy by granting loans to the Ottoman state.[59]

In 1840, the amiras received their second blow when a new Patriarchal Advisory Committee was formed consisting of only two salaried amiras, while the majority of its members were from the esnafs.[60] This was the first time in their history that these amiras were underrepresented. Opposition had already started between the two groups, since the elections of 1834 when the amiras took control of the above mentioned Committee, while no esnaf was given the opportunity to take part in it. [61]

In addition to this event, a rivalry also took place between the amiras themselves; mainly the sarraf amiras and government salaried amiras, who were supported by the merchants and the artisans respectively.[62] The conflict started over the management of the College in Uskudar, which was established by the amiras in 1838.[63] Initially, the expenses of the institution were covered by the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem and the sarraf amiras. However, after the abolition of tax-farming, the sarraf amiras were placed in a miserable situation, since they no longer owned the financial means to support this establishment.[64] Moreover, the sarraf amiras asked the Patriarchate of Jerusalem to stop sending money to the College in view of the fact that most of the students attending this school were the children of the esnafs.[65] Hence, they inflicted harm on the esnafs by creating a boundary in the education of their youngsters. In addition, the newly formed Committee of esnafs was unable to manage the finances of the Armenian millet in the absence of the sarrafs. Hence, it resigned.[66]

After a short while, the artisans petitioned Sultan Abdul Mecid to restore the Committee. He verbally reinstated it without issuing an official ferman. Artinian attributes the Sultan’s act as being the product of the Armenian sarrafs’ intervention, who had influence over the Sultan. However, the second time they petitioned for the same issue they were all imprisoned.[67] It can be implied that the sarraf amiras strived to be part of the course of events taking place within the life of the Armenian millet, and worked to distort it when deprived of this privilege.

Finally, after 1856, with the start of the Armenian Constitutional Movement, the Armenian amiras lost all their seats in the Patriarchate’s Supreme Civil Council. They were removed from the scene and replaced by a group of Western-educated young Armenians known as the Young Armenians and the esnafs.[68]

Conclusion:

In conclusion, during the state’s efforts towards modernization and westernization, the Armenian amira class also played a significant role as well. Even though, the amiras searched their personal benefits and gains, they put their wealth to serving the Armenian society at large. Hence, this period could be characterized as a golden era of progress for the Armenian millet.

Bibliography

Artinian, Vartan. “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional

System in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1863.” PhD diss., Brandeis University, 1970.

Barsoumian, Hagop. “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul.” PhD diss., Columbia University,

1980.

Barsoumian, Hagop. “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class within the Ottoman

Government and the Armenian Millet (1750-1850).” In Christians and Jews in the Ottoman

Empire Volume I: The Central Lands, edited by Benjamin Braude and Bernard Lewis. New

York, London: Holmes and Meier Publishers, 1982.

Inal, Vedit. “The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Ottoman Attempts to Catch Up with

Europe.” Middle Eastern Studies 47/5 (2011): 725-756.

Sources:

[1]Vartan Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1863,” (PhD diss., Brandeis University, 1970), 4.

[2] Hagop Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul” (PhD diss. Columbia University, 1980), 2.

[3] Ibid, 49.

[4] Ibid, 51.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, 50.

[7] Ibid, 51.

[8] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 21.

[9] Ibid, 27.

[10] Ibid, 60.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, 61.

[13] Ibid, 70.

[14] Ibid, 73.

[15] Ibid, 62.

[16] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 83.

[17] Ibid, 68.

[18] Ibid, 64.

[19] Ibid, 65.

[20] Ibid, 81.

[21] Ibid, 82-83.

[22] Ibid, 72.

[23] Ibid, 90.

[24] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 91.

[25] Ibid, 94.

[26] Ibid, 95.

[27] Hagop Barsoumian, “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class in the Ottoman Government and the Armenian Millet (1750-1850),” in Christians and Jews of the Ottoman Empire, Volume I: The Central Lands, eds. by Benjamin Braude and Bernard Lewis (New York, London: Holmes and Meier Publishers, 1982), 175.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 116, 124.

[30] Barsoumian, “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class,” 175.

[31] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 101-102.

[32] Vedit Inal, “The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Ottoman Attempts to Catch Up with Europe,” Middle Eastern Studies 47, no. 5 (2011): 734.

[33] Barsoumian, “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class,” 174.

[34] Inal, “The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Ottoman Attempts,” 735.

[35] Ibid, 738.

[36] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 111.

[37] Ibid, 112-113.

[38] Inal, “The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Ottoman Attempts,” 745.

[39] Barsoumian, “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class,” 112.

[40] Inal, “The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Ottoman Attempts,” 736.

[41] Ibid, 740.

[42] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 140.

[43] Barsoumian, “The Dual Role of the Armenian Amira Class,” 177.

[44] Ibid, 180.

[45] Vartan Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System,” 21.

[46] Ibid, 27.

[47] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 141.

[48] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 142.

[49] Ibid, 143.

[50] Ibid, 144.

[51] Ibid, 146.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid, 147.

[54] Ibid, 148.

[55] Ibid, 149.

[56] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 156.

[57] Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System,” 21.

[58] Barsoumian, “The Armenian Amira Class of Istanbul,” 105.

[59] Ibid, 107-108.

[60] Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System,” 52.

[61] Ibid, 27.

[62] Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System,” 52-53.

[63] Ibid, 52.

[64] Ibid, 53.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid, 54.

[67] Ibid, 55.

[68] Artinian, “A Study of the Historical Development of the Armenian Constitutional System,” 80.

Bedros Torossian is a senior undergraduate History student at the American University of Beirut. Late Ottoman educational life lies within his area of research. He has recently published an article called “Roles of Turkish and American Orphanages in Influencing Armenian Identities” in Haigazian Armenological Review in 2016. “