Introduction

Following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Armenian economy collapsed. Starting in 1993, the government took a neo-liberal path and launched an ambitious IMF-sponsored economic reform by privatizing most public companies. As a result, a small elite concentrated political and economic power into their hands and ruled the country until 2018. Before the “Velvet Revolution” (April 2018), which toppled the Republican Party ruling elite, the lack of governmental accountability, bad governance, and systemic corruption was a severe threat to Armenia’s environment. Under the “oligarchic”[1] system, the environment fell prey to the economic interests of the business elite who occupied key positions in both executive and legislative branches of the government.[2] Due to the trade blockade imposed by Azerbaijan and Turkey (1990 and 1993 respectively), because of the Nagorno-Karabakh war (1990-1994), the Armenian leadership chose the path of extractive economic and political institutions, and the mining sector was seen as the locomotive of Armenia’s economic growth.

Despite the negligible contribution of the mining sector to Armenia’s GDP, mining accounted for over half of all exports.[3] With almost 700 mines in operation, mining is considered an important economic sector in Armenia. Mining is the biggest recipient of foreign investment in the country.[4]

However, the absence of clear mining policy and strategy in Armenia gave birth to two debates:

The first debate is supported by the mining industry, international agencies, and industrialists which claim that the mining sector will create jobs in rural and impoverished areas, and have a positive impact on the economy. They argue that they will protect the environment from any damage and will also take measures to rehabilitate the area after mining is complete.

However grassroots environmental justice activists such as the Armenian Ecological Front and other “Civic initiatives” believe that the way mining is conducted has disastrous consequences on the environment and the well-being of the citizens. This second debate concentrates on the idea that under neoliberalism mining is harmful. Mining and mine tailing have led to widespread deforestation and contaminated rivers. Environmentalists argue that direct action against mining operations is justified because they have a moral obligation to ensure that future generations of Armenians would inherit a country whose rivers, land, and air aren’t contaminated with heavy metals.

With the resignation of former PM Serzh Sarkissyan in April 2018, the ousting of the Republican Party from power, and the rise to power of civil society backed PM Nigol Pashinyan, environmental activists thought their chances to stop the mining was high. However, they were soon to be disappointed. As protestors closed the roads to the mines, the mining industry issued warnings and called the government to use violence to expel them. Hence the new government was stuck between the two debates. The new PM was under huge pressure from both sides. On one hand, he was hoping to avoid alienating the activists who helped bring him to power, but on the other hand, he needed to attract foreign investment to fulfill his promises of economic growth and development.

The paper will address how these debates are contextualized within the discourse of post-revolutionary Armenia. In a neoliberal economic system, where the discourse rotates around economic growth, sometimes the environment falls prey to industrialization and foreign investments. I will highlight the main debates argued by international and local mining industries, economists, and environmentalist grassroots activists taking case study the example of “Amulsar” mining in Armenia. The paper will explain how Armenia’s mining sector developed under neoliberalism, identify the key environmentalist movements, their disagreements, and demands and finally analyze the role of international actors, wealthy businessmen and political actors that shape the debates in post-revolutionary Armenia. The paper will be divided into four sections. In the first section, I will introduce the two key debates, research question, and the methodology. In the second section, I will briefly explain how mining as a global trend is perceived in third world countries, under what conditions it was developed in Armenia and how the first fruits of resistance were born. The third section will illustrate the two debates which preceded and later developed after the revolution, the clash of the interests and the government’s position. The conclusion will be a reflection and a summary of the debates. Primary data such as social media posts, academic papers, articles, and official statements will be analyzed. Discourse analysis will be employed to analyze the neoliberal discourse when it comes to economic growth in developing countries and the fact that the environment falls prey for the interest of profit-makers. I will highlight and analyze the main narratives used by both sides that fostered these debates. With the political openness after the April 2018 revolution, these debates were also moved to social media, where both sides used this arena for its own benefit to promote their ideas and engage in a “war propaganda”.

Neo-liberalism, mining, and fruits of “Civic Initiatives”

With the fall of the Soviet Union, Armenia tried to catch up Eastern European states with a quick introduction of neoliberal economic policies. Mining was positioned within this context and the environment and other industries fell prey to this sector. As a result, a new wave of environmental justice movement spread in Armenia whose aim was not just a fight for environmental rights but also broader speaking about the socio-economic wellbeing of the citizens.

- The “Dutch disease” hits Armenia

In 1977 the Economist first coined the term “Dutch Disease” referring to the poor management of the natural gas sector in the Netherlands.[5] The natural gas sector began dominating the economy at the expense of other sectors, leaving the country highly dependent on natural resources’ quantity and price.[6] Later, the term was used to describe similar cases that faced booming in natural resources and a decline in other industrial sectors. The dependence on exporting raw materials prevents states to be industrialized and promotes extractive economic systems. Thus, there will be an imbalance between different industrial sectors and labor will flow towards extractive sectors creating a “de-industrialization” process.[7] Later this trend has been widely used in Africa, Latin America and other third world countries. Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) argue that extractive economic institutions developed by states only benefit a narrow segment of elites. [8] This in its turn widens the gap between different social and economic classes and produces social inequality. The debates around mining have focused on the theory of “Dutch disease” arguing that countries rich with mineral resources are being overexploited by powerful countries and corporations. [9]

At the beginning of 1980s mining began to move from the global North to the global South. Since foreign investors were attracted to countries with less stringent environmental policies. For many, this was seen as a new form of imperial expansion.[10] Armenia with its rich mining mineral resources and lax mining regulations was attractive to many foreign mining companies.

- Neo-liberalism and the development of the mining industry in Armenia

Soil is a basic environmental component of our ecosystem and vital for our survival, but at the same time, it is the most endangered component and opens to be intoxicated from various man-made pollutions. Heavy metal is a dangerous group of soil pollutants because simply they cannot be naturally degraded and are able to accumulate in the different parts of the food chain.[11] Heavy metal pollution poses risks to agricultural production and the health of the people living in the territory.[12] Mining and smelting operations are the main causes of heavy metal contamination due to activities such as mineral excavation, and disposal of tailings and wastewater around the mines. The heavy metal pollution not only threatens the food chain but also causes respiratory problems especially among children and the elderly. [13]

When Armenia gained independence from the Soviet Union, the government privatized many public sectors. The mining sector was privatized in 1999 with a lenient taxation system and almost with no quantitative trade restriction in order to attract foreign direct investment.[14] By 2005 Armenia was considered the country of the most favorable investment environment in the region.[15] It should be noted that development aid and technical assistance to the post-Soviet countries arrived “ideologically packaged”.[16] Moreover, capitalism was never questioned and any anti-capitalist opposition was suppressed under the pretext of “communist return”. It was during this period that many donor-driven, and upwardly accountable civil society groups and NGOs flourished. These organizations were disconnected from local communities, marginalized the poor or less educated people, and were viewed with hostility from conservative societies.[17]

In Armenia anti-mining activism emerged as a result of the introduction of neoliberal policies and practices and the failure of NGOs and civil societies to solve the environmental issues.[18] Resistance to mining was organized by city-based students and youth locally known as “Civic Initiatives”.[19] Unlike other environmentalist groups, “Civic Initiative” groups such as the Armenian Ecological Front, refused any foreign aid, adopted radical steps- such as violence-since they viewed the environmental problem as part of state-sponsored corruption supported by Western-backed neoliberal funding.[20] This new wave of civic activism was a result of youth frustration and anger from donor-oriented NGOs where people lost their hope and lacked trust in them. This is why they reject the “NGOization” of the civil society and describe themselves as “self-determined” citizens who put greater emphasis on independence, indigenous solidarity and self-organization and call people to become the “owners” of their towns and villages. [21] [22]

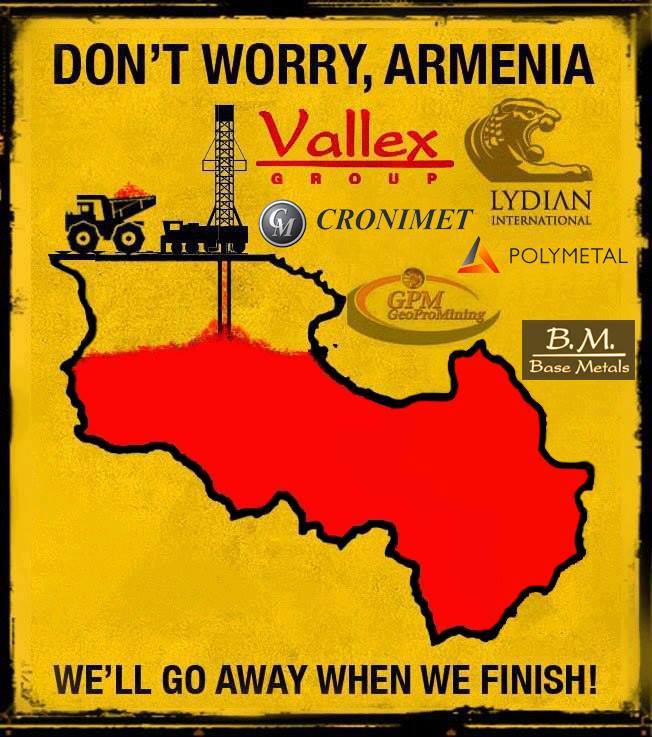

Figure 1: A poster prepared by the Armenian Environmental Front “Dig Armenia until dry” ArmEcoFront / Facebook.

These groups are distinct from NGOs, they are informal, volunteer-based, horizontally structured, lack organizational hierarchy, and most importantly they reject to receive any funding from donors or governments.[23] It is important to note that horizontality is valued since active participation of all members are encouraged and decisions are made by consensus agreement. Unlike the older generation who argue that the state must provide services, they raise awareness that it is peoples’ responsibility to clean up parks and defend public property.[24] They argue that environmental problems are connected to the systematic corruption, uncontrolled overexploitation and social injustice that Armenia is facing. Their protests target international development agencies which fund mining projects and government which support their neoliberal policies. Their practices and discourses are partly shaped by global trends and influenced by radical leftist anti-establishment ideas. For example in 2012 several “Occupy movements” were emerged in post-Soviet countries, while they challenged the corruption and authoritarian governments, they also embraced anti-neo liberal ideas.[25] Under this context, similar to the environmental justice movements in the US, the protests by the “Civic Initiative” groups were not only against environmental issues but also about human rights, political participation, and social justice.

The emergence of two debates in post-revolutionary discourse

Two debates have developed regarding the mining sector in Armenia, the post-“Velvet Revolution” government whose aim was to bring stability and economic prosperity found wedged between two non-compromising interests. The first debate was formulated by the environmentalist activists who played important role in bringing the Pashinyan to power, while the second debate was based on the interest of international agencies and industrialists who promised to bring foreign investment and economic development through the mining industry.

- Economy First!

The mining sector and its supporters argue that the sector will bring economic development and will not harm the environment. “Lydian Armenia” mining company, registered in a British tax haven and headquartered in the U.S. with shareholders from US, Canadian and European banks and investment funds, used Armenia’s corrupt mining legacy to its advantage.[26] The company advanced a narrative arguing that it will be an example of responsible mining in Armenia and bring lasting economic benefits. The company with the support the foreign and local economic lobbies advanced the discourse that mining is important in Armenia and it will bring development and economic growth.

For many industrialists, it is poverty and not mining the major threat to Armenia. They argue that in the period from 2008-2016, “Lydian Armenia” has paid over 3.3 million USD to different municipalities and this money was invested in heating systems in the schools so that “children don’t have to wear coats in the classroom”.[27] Moreover, roads and highways were renovated through these funds. The proponents of mining simply argue that mining is the backbone of the economies in Canada and Sweden, both countries meet high international environmental standards.[28] “Lydian Armenia” also argues that it has produced an “Environmental and Social Impact Assessment” of more than 5500 pages, written by the best environmental scientists in Armenia and worldwide, and spent 6 million USD for this purpose.[29] Nevertheless, they complain that any opposition would endanger the flow of foreign investment to the country. Hayk Aloyan (2017), the Managing Director of Lydian Armenia, argues that strong economies are created by investments. Thus Armenia must ensure a healthy investment climate. For them, business and environmental integrity are not mutually exclusive, both complement each other.[30] Since business needs to make a profit so that society benefits from investments. Thus the success of Amuslar will be a success story which will attract further foreign investments in the near future.

Lara Ghazaryan, the Social Sustainability Manager at “Lydian Armenia” claims that mining has direct and indirect benefits for Armenia’s economy.[31] First, it creates jobs, citing that over 1300 people work in Amuslar mining, they get the highest salaries compared to other sectors, and 40% of the workforce comes from the surrounding villages. Based on the company’s assumption, when the production starts, 700 permanent jobs will be opened and they expect to pay 40-50 million USD in taxes to the state budget annually.[32] Already Lydian Armenia is one of the largest taxpayers in the country.

As environmental activists blocked the roads towards the mines, a propaganda war was waged on social media between the advocates of both sides. The supporters of the mining industry argued that the majority of the protestors come from NGO background, based in Yerevan, that is far from the mining sites, and do not possess any scientific knowledge about mining and environment, rather than the “dogmatic notion that mining is harmful”.[33]Armen Stepanyan, Lydian Armenia Company’s Sustainability Director, has refuted all the accusation from the environmentalists saying that the company will take all the necessary measures to rehabilitate the area after the mining is finished.[34] He also has stated that all unnecessary infrastructure will be removed and the land be returned to the previous owners.[35] However, Aragon and Rud (2012), argue that even if mines are returned back to the farmers, the land needs decades to be used for agricultural purposes.[36] When environmentalists suggested supporting local agriculture (such as exporting local honey since the tone of honey is more profitable than a tone of copper and tourism instead of mining), Aloyan (2017) sarcastically responded by asking that Armenia annually exports 1000 tons of copper, can the country export the same amount of honey?[37] He also has cited the example of Australia saying that thanks to mining, once an agrarian society now it is a modern industrial state.[38]

Finally, Lydia Armenia supporters claim that the accusations of the environmentalist are just “myths” and do not meet scientific standards. [39] They have responded to the accusation by citing a number of “independently conducted environmental impact studies” demonstrating that the company complies with the strictest international environmental safety standards.[40] These findings were confirmed and refuted by the European Bank of Development (major shareholder at Lydian), International Finance Corporation and the World Bank.[41] The World Bank report provides a historical review of the Armenian mining sector and assesses how it can contribute to “sustainable economic growth and development”. The report also claims that there is a significant amount of small mining companies that are poorly managed and cannot be seen as environmentally sustainable projects and the government needs to come up with adequate plans and fund to rehabilitate the mine sites.[42] Finally, the report mentions that the factors behind the lack of environmental sustainability are a result of companies’ irresponsible behavior and failure of supervising and monitoring activities charged on some institutions.[43]

- “Amuslar Will Remain a Mountain!”

People haven’t protested before since they felt the “Lydian Armenia” was protected by the corrupt state. However, as the government collapsed and a new popular government was installed, locals realized their voice would be heard.[44]

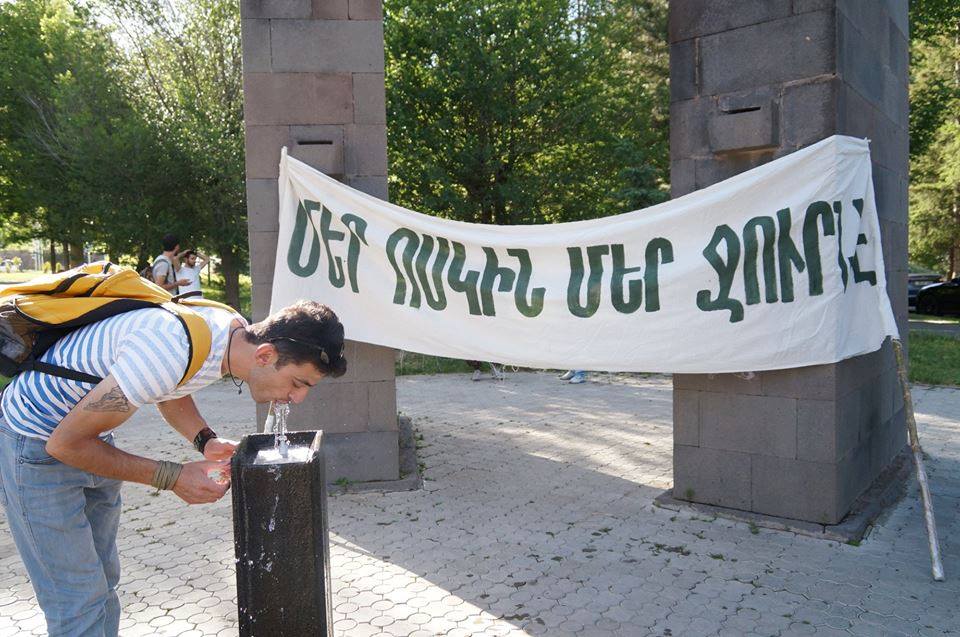

Photograph taken in Jermuk, the poster reads, “Our gold is our water.” (Photo: Tehmine Yenokyan)

Roughly 70 people gathered and discussed what should be done about the mine in the area.[45] There was no direct voting, and there were no official leaders, instead, there was a slow process of generating consensus. The people were composed of youth and Karabakh war veterans. Thus, some in the protestors had military discipline and knew guerrilla tactics, these tactics were used in blockading the roads and destroying the infrastructure of the mining company.[46] As violence intensified between the activists chanting “Amuslar will remain a mountain” and mine workers worried about their future, the mining company asked the government to use violence to expel the protesters.[47]

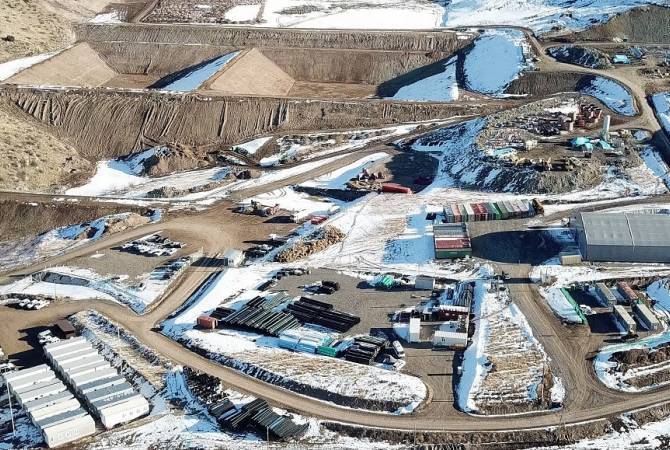

Locals started to complain that tourism in the area is in decline because of the mining project. Gevorg Safaryan, member of the environmental “Civic Initiative”, believes that the mine at Amuslar is like a toxic bomb planted under Armenia’s water resources. For him, the mine, which is located not far from the Lake Sevan, the country’s largest source of freshwater, not only pollutes the freshwater but is also a strategic danger to the state.[48]

However, the activists also point out criticism of foreign actors too. Anna Shahnazaryan, an environmentalist from the Armenian Ecological Front, believes that there is strong international pressure coming from the US and Britain on behalf of “Lydian Armenia” on the new Armenian government.[49] The Armenian Environmental Front Civic Initiate has accused the European Bank of Development of not only supporting and financing the Amuslar mining project but also of Western colonization driving the villagers from their farms. Arguing that this in itself is a colonial mindset which is engaged in modern economic colonization. [50] For the environmental justice activists, Amuslar symbolizes the expansion of corporate greed at the expense of the environment and the peoples’ health.[51]

These activists claim that mining has called health issues and caused environmental damages. They complain that mining activities have not been properly regulated or monitored and have increased poverty in the area and pushed families or migrate from rural areas.

However, some activists are taking other initiatives. They have raised the issue of leopard migration and Amuslar is an intersection point where Leopards migrate during different seasons. In order to protect this endangered animal, environmentalists demanded to preserve these areas and raised concerns that mining activities would destroy the forests and contaminate the waters drank by the villages and leopards.[52] They are hopeful that several regional environmental organizations would join in their lobbying activities and eventually the government would interfere on their behalf. Nevertheless, until now the activists failed to reach into a solution and the court ordered to put an end for all kind of protests around the mining site.[53]

- The First Exam: Fail or Pass!

The new PM, Nigol Pashinyan, once a sympathizer of the environmentalist front, was forced to mediate between the grassroots activists who brought him to power and western companies and investors who promise to bring economic development that his government so badly needs. Pashinyan, while ago a fierce opposition voice to mining, when he visited Amuslar he called the activists to “face facts rather than emotions”.[54] Pashinyan was even criticized from his close circles such as Erik Grigoryan the Minister of Nature Protection who expressed his opposition to Amuslar project. [55]

Pashniyan, now views their action as a possible threat to his authority and a danger to his country’s international economic standing. On June 25, in one of his famous Facebook live streams, he criticized the protestors by stating that they are sabotaging and creating a deadlock situation for the government. He even went further and called to halt the civil disobedience.[56] However, by calling the actions of the activists as sabotage, the PM contradicted himself, since he used the same tactics while toppling the ruling government in April 2018.[57] Meanwhile, encouraged by the PM’s statement, “Lydian Armenia” threatened that if the government takes a decision to shut down the company then legal action will be taken and the government will be sued in international courts for compensation thus tarnishing the image of the new government.[58] It is clear that Armenia’s low annual budget and high level of state depth is being exploited by the company to impose pressure on the government.[59] Thus blocking all the maneuvering options for the government.

As the conflict of interests between the protestors and the company intensified on one hand, and the government’s inability to solve the crisis was clear on the other hand, foreign pressure increased on the government. The US ambassador interfered to increase more pressure by stating that Lydian will continue to serve as an example of “responsible mining operating transparently in line with international environmental and social standards”.[60] Nevertheless, by commenting on the protests he said that the US is pleased to see Armenia conducting an environmental audit of Lydian’s Amuslar project.[61] In parallel, the American Chamber of Commerce in Armenia, a leading US business association in America, which works closely with the US embassy in Yerevan, welcomed the PM’s decision to bring “international best practice” into the mining sector in Armenia, considering the non-deniable role that the mining sector plays in the Armenian economy.[62] By making such statements, the Americans showed that the continuation of the mining project was important for them and any termination may harm the American-Armenian business relations.

Finally, few realize that by polluting Armenian’s main freshwater sources, the country will be risked to import freshwater from outside, thus increasing its dependence on regional countries. Armenia which is trying to minimize its economic dependence on Russia may find itself forced to import freshwater from Moscow. The latter, similar to the flow of gas to Armenia where it has been monopolized by the Russian state-led Gazprom company, will use this opportunity to increase its political leverage by using the “water weapon” against Yerevan’s new Moscow-viewed[63] “pro-Western” government.

The project has turned into an official exam causing anxiety to the ruling elite and a challenge both on domestic and international fronts.

Conclusion

It is not clear, how and when the government will come into a final conclusion regarding this matter. One thing it is apparent that the maneuvering spaces for the government are limited. The environmental justice movements are fighting to halt all mining activities in the country. It is clear that for them Amuslar is just the beginning. If they succeed then they will move to other targets. On the other hand, there is a popular demand to put an end to poverty, unemployment, and emigration. The people, especially the youth who were the dominant force behind the revolution are hoping for a stable and prosperous future. Meanwhile, mining companies, international agencies, and some industrialists are escalating pressure on the government to take quick decision in their favor or else the country’s international image will be tarnished, and foreign investments will be halted. Between these two conflicting debates, the government may find a middle way and continue pursuing negotiations with both sides. While PM Pashnyan is thirsty for foreign investments, at the same time he is cautious not to alienate the activists and encourage internal opposition within the ruling elite. The mining sector which may promise to open new jobs and attract foreign investment may also cause a severe environmental crisis. “To mine or not to mine” or try to find a middle way, either way, the government has to decide to sit for the exam.

Bibliography:

– Acemoglu, Daron and Robinson, James, “Why Nations Fail; The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty”, Profile Books, Great Britain, 2013

– Aloyan, Hayk. Poverty is the Real Threat, February 8, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12721/

-Aloyan, Hayk. The Simple Secret of Strong Economy, November 6, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12770/

– Aragon, Fernando M. and Pablo Rud, Juan, Mining, Pollution and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Ghana, Dartmouth College, https://www.dartmouth.edu/~neudc2012/docs/paper_7.pdf, September 2012

-Armenian Ecological Front, EBRD Shares Responsibility for the Amulsar Mine Crisis in Jermuk, March 9, 2019, http://www.armecofront.net/en/amulsar-2/ebrd-shares-responsibility-for-the-amulsar-mine-crisis-in-jermuk/

– Bennett, Catherine. Armenian activists fight to shut down gold mine, save their water, 13/7/2018, https://observers.france24.com/en/20180713-armenian-activists-fight-shut-down-gold-mine-save-water.

-Elliott, Raffi. Court Orders Removal of Amuslar Mine Protestors, Armenian Weekly, 17/4/2019, https://armenianweekly.com/2019/04/17/court-orders-removal-of-amulsar-mine-protesters/

– Elliott, Raffi. Are We Overdoing Civil Disobedience? Armenian Weekly, July 4, 2018, https://armenianweekly.com/2018/07/04/are-we-overdoing-civil-disobedience/

-Ellis, Glesnn. Mining vs the environment: The battle over Armenia’s Amuslar gold mine, Al Jazeera, 31/1/2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/blogs/europe/2019/01/mining-environment-battle-armenia-amulsar-gold-190130135537637.html

– Gevorgyan, A., Movsesyan, H.S., Grigoryan, K.V., Ghazaryan, K.A. Environmental Risks of Heavy Metal Polution of the Soils around Kajaran Town, Armenia, Proceedings of the Yerevan State University, No. 2, 2015, http://ysu.am/files/13.%20ENVIRONMENTAL%20RISKS%20OF%20HEAVY%20METAL%20POLLUTION%20OF%20THE%20SOILS%20AROUND%20KAJARAN%20TOWN,%20ARMENIA.pdf

-Huseynov, Vasif and Rzayev, Ayaz. The ‘Velvet Revolution” is affecting Armenia’s ties with Russia, Euractive, 23/10/2018, https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/opinion/the-velvet-revolution-is-affecting-armenias-ties-with-russia/

– Iskhanian, Armine. Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

-Iskhanian, Armine. Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

– Ishkanian, Armine. Self-determines Citizens? A new wave of civic activism in Armenia, 16/6/2015, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/selfdetermined-citizens-new-wave-of-civic-activism-in-armenia/

-Jardine Bradley and Atanesian Grigor. Mining dispute threatens Armenia’s post-revolutionary political consensus, 24/7/2018, https://eurasianet.org/mining-dispute-threatens-armenias-post-revolutionary-political-consensus

– Liakhov, Peter and Khudoyan Knar. How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

– Nazaretyan, Hovhannes, Amuslar: Gold Over Water?, EVN report, https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/amulsar-gold-over-water, July 3, 2018

– Sahakyan, Arpine. Dutch Disease in Armenia: by Sector Study, Armenian Economic Association, 2014, http://www.aea.am/files/papers/w1510.docx

-_________.Armenia: Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment, The World Bank, April 2016, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/289051468186845846/Armenia-Strategic-mineral-sector-sustainability-assessment

-__________.ArmCham Armenia Supports Responsible Business in Armenia, https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=182

-_________. Corruption in Armenia, Public Policy Forum, 21/10/2013, http://www.pf-armenia.org/document/corruption-armenia

-________. Myths and Reality about Mining,

https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=69

-__________.U.S. Hopes for ‘Impartial’ Audit of Amuslar Mining Project, Asbarez, 11/7/2018, http://asbarez.com/173660/u-s-hopes-for-impartial-audit-of-amulsar-mining-project/

-__________Talk: Environmental Justice in Armenia and Amuslar Mine Project, 15/11/2018, https://armenianweekly.com/2018/11/15/talk-environmental-justice-in-armenia-and-the-amulsar-mine-project/

-_________. What Dutch disease is, and why it’s bad, The Economist, 5/11/2010, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/11/05/what-dutch-disease-is-and-why-its-bad

-_________. 14 Questions and Answers about Amuslar, Lydian Armenia https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=168

[1] Oligarchy means a small group of wealthy people having control of a country.

[2] “Corruption in Armenia”, Public Policy Forum, 21/10/2013, http://www.pf-armenia.org/document/corruption-armenia

[3] The World Bank, “Armenia: Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment”, April 2016, https://crm.aua.am/files/2018/05/Armenia_strategic_assessment-eng.pdf

[4] The World Bank, “Armenia: Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment”, April 2016, https://crm.aua.am/files/2018/05/Armenia_strategic_assessment-eng.pdf

[5] “What Dutch disease is, and why it’s bad”, The Economist, 5/11/2010, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/11/05/what-dutch-disease-is-and-why-its-bad

[6] “What Dutch disease is, and why it’s bad”, The Economist, 5/11/2010, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/11/05/what-dutch-disease-is-and-why-its-bad

[7] Arpine Sahakyan, “Dutch Disease in Armenia: by Sector Study”, Armenian Economic Association, 2014, http://www.aea.am/files/papers/w1510.docx

[8] Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, “Why Nations Fail; The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty”, Profile Books, Great Britain, 2013, p. 16

[9] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[10] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[11] .A. Gevorgyan, H.S. Movsesyan, K.V. Grigoryan, K.A. Ghazaryan, “Environmental Risks of Heavy Metal Polution of the Soils around Kajaran Town, Armenia”, Proceedings of the Yerevan State University, No. 2, 2015, p. 51, http://ysu.am/files/13.%20ENVIRONMENTAL%20RISKS%20OF%20HEAVY%20METAL%20POLLUTION%20OF%20THE%20SOILS%20AROUND%20KAJARAN%20TOWN,%20ARMENIA.pdf

[12] G.A. Gevorgyan, H.S. Movsesyan, K.V. Grigoryan, K.A. Ghazaryan, “Environmental Risks of Heavy Metal Pollution of the Soils around Kajaran Town, Armenia”, Proceedings of the Yerevan State University, No. 2, 2015, p. 51, http://ysu.am/files/13.%20ENVIRONMENTAL%20RISKS%20OF%20HEAVY%20METAL%20POLLUTION%20OF%20THE%20SOILS%20AROUND%20KAJARAN%20TOWN,%20ARMENIA.pdf,

[13] .A. Gevorgyan, H.S. Movsesyan, K.V. Grigoryan, K.A. Ghazaryan, “Environmental Risks of Heavy Metal Pollution of the Soils around Kajaran Town, Armenia”, Proceedings of the Yerevan State University, No. 2, 2015, p. 55, http://ysu.am/files/13.%20ENVIRONMENTAL%20RISKS%20OF%20HEAVY%20METAL%20POLLUTION%20OF%20THE%20SOILS%20AROUND%20KAJARAN%20TOWN,%20ARMENIA.pdf,

[14] Armine Ishkanian, “Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia”, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

[15] Armine Ishkanian, “Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia”, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

[16] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[17] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[18] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[19] Armine Ishkanian, “Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia”, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

[20] Armine Ishkanian, “Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia”, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

[21] Armine Ishkanian, “Self-determines Citizens? A new wave of civic activism in Armenia”, 16/6/2015, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/selfdetermined-citizens-new-wave-of-civic-activism-in-armenia/

[22] Armine Ishkanian, “Self-determines Citizens? A new wave of civic activism in Armenia”, 16/6/2015, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/selfdetermined-citizens-new-wave-of-civic-activism-in-armenia/

[23] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[24] Armine Iskhanian, “Civil Society, Development and Environmental Activism in Armenia”, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013, https://transparency.am/en/publications/view/189

[25] Armine Ishkanian, “Challenging the Gospel of Neoliberalism? Civil Society Opposition to Mining in Armenia”, 2016, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64900/

[26] “U.S. Hopes for ‘Impartial’ Audit of Amuslar Mining Project”, Asbarez, 11/7/2018, http://asbarez.com/173660/u-s-hopes-for-impartial-audit-of-amulsar-mining-project/

[27] Hayk Aloyan, Poverty is the Real Threat, February 8, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12721/

[28] Hayk Aloyan, Poverty is the Real Threat, February 8, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12721/

[29] Hayk Aloyan, Poverty is the Real Threat, February 8, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12721/

[30] Hayk Aloyan, Poverty is the Real Threat, February 8, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12721/

[31] 14 Questions and Answers about Amuslar, Lydian Armenia https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=168

[32] 14 Questions and Answers about Amuslar, Lydian Armenia https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=168

[33] Raffi Elliott, Are We Overdoing Civil Disobedience? Armenian Weekly, July 4, 2018, https://armenianweekly.com/2018/07/04/are-we-overdoing-civil-disobedience/

[34] Hovhannes Nazaretyan, “Amuslar: Gold Over Water?” EVN report, https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/amulsar-gold-over-water, July 3, 2018

[35] Hovhannes Nazaretyan, “Amuslar: Gold Over Water?” EVN report, https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/amulsar-gold-over-water, July 3, 2018

[36] Fernando M. Aragon and Juan Pablo Rud, “Mining, Pollution and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Ghana”, Dartmouth College, https://www.dartmouth.edu/~neudc2012/docs/paper_7.pdf, September 2012

[37] Hayk Aloyan, The Simple Secret of Strong Economy, November 6, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12770/

[38] Hayk Aloyan, The Simple Secret of Strong Economy, November 6, 2017, https://www.mediamax.am/en/column/12770/

[39] Myths and Reality about Mining, https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=69

[40] Raffi Elliott, Are We Overdoing Civil Disobedience? Armenian Weekly, July 4, 2018, https://armenianweekly.com/2018/07/04/are-we-overdoing-civil-disobedience/

[41] Armenia: “Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment”, World Bank, April 2016, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/289051468186845846/Armenia-Strategic-mineral-sector-sustainability-assessment

[42] Armenia: “Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment”, World Bank, April 2016, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/289051468186845846/Armenia-Strategic-mineral-sector-sustainability-assessment

[43] Armenia: “Strategic Mineral Sector Sustainability Assessment”, World Bank, April 2016, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/289051468186845846/Armenia-Strategic-mineral-sector-sustainability-assessment

[44] Catherine Bennett, “Armenian activists fight to shut down gold mine, save their water”, 13/7/2018, https://observers.france24.com/en/20180713-armenian-activists-fight-shut-down-gold-mine-save-water,

[45] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[46] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[47] Catherine Bennett, “Armenian activists fight to shut down gold mine, save their water”, 13/7/2018, https://observers.france24.com/en/20180713-armenian-activists-fight-shut-down-gold-mine-save-water,

[48] Hovhannes Nazaretyan, “Amuslar: Gold Over Water?” EVN report, https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/amulsar-gold-over-water, July 3, 2018

[49] Hovhannes Nazaretyan, “Amuslar: Gold Over Water?” EVN report, https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/amulsar-gold-over-water, July 3, 2018

[50] Armenian Ecological Front, “EBRD Shares Responsibility for the Amulsar Mine Crisis in Jermuk”, March 9, 2019, http://www.armecofront.net/en/amulsar-2/ebrd-shares-responsibility-for-the-amulsar-mine-crisis-in-jermuk/

[51] “Talk: Environmental Justice in Armenia and Amuslar Mine Project”, 15/11/2018, https://armenianweekly.com/2018/11/15/talk-environmental-justice-in-armenia-and-the-amulsar-mine-project/

[52] Glesnn Ellis, “Mining vs the environment: The battle over Armenia’s Amuslar gold mine”, Al Jazeera, 31/1/2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/blogs/europe/2019/01/mining-environment-battle-armenia-amulsar-gold-190130135537637.html

[53] Raffi Elliott, “Court Orders Removal of Amuslar Mine Protestors”, Armenian Weekly, 17/4/2019, https://armenianweekly.com/2019/04/17/court-orders-removal-of-amulsar-mine-protesters/

[54] Bradley Jardine and Grigor Atanesian, “Mining dispute threatens Armenia’s post-revolutionary political consensus”, 24/7/2018, https://eurasianet.org/mining-dispute-threatens-armenias-post-revolutionary-political-consensus

[55] Bradley Jardine and Grigor Atanesian, “Mining dispute threatens Armenia’s post-revolutionary political consensus”, 24/7/2018, https://eurasianet.org/mining-dispute-threatens-armenias-post-revolutionary-political-consensus

[56] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[57] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[58] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[59] Peter Liakhov and Knar Khudoyan, “How Citizens battling a controversial gold mining projects are testing Armenia’s new democracy”, 7/8/2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-liakhov-knar-khudoyan/citizens-battling-a-controversial-gold-mining-project-amulsar-armenia

[60] “U.S. Hopes for ‘Impartial’ Audit of Amuslar Mining Project”, Asbarez, 11/7/2018, http://asbarez.com/173660/u-s-hopes-for-impartial-audit-of-amulsar-mining-project/

[61] “U.S. Hopes for ‘Impartial’ Audit of Amuslar Mining Project”, Asbarez, 11/7/2018, http://asbarez.com/173660/u-s-hopes-for-impartial-audit-of-amulsar-mining-project/

[62] ArmCham Armenia Supports Responsible Business in Armenia, https://www.lydianarmenia.am/index.php?m=newsOne&lang=eng&nid=182

[63] Vasif Huseynov and Ayaz Rzayev, “The ‘Velvet Revolution” is affecting Armenia’s ties with Russia”, Euractive, 23/10/2018, https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/opinion/the-velvet-revolution-is-affecting-armenias-ties-with-russia/