Turkey, under President Erdogan, is increasingly pursuing a proactive foreign policy designed to achieve four objectives: challenge the regional status quo, forge a global leadership role, enhance the regime’s domestic legitimacy and ensure its survival. Central Asia plays a key role in Erdogan’s domestic, trade and geopolitical calculations. Turkey’s mixed blessing in the South Caucasus and the establishment of new trade routes have enhanced Ankara’s ability to project its influence in Central Asia. As Turkey began temporarily distancing itself from the West, it started looking eastward where natural resources, investment and business opportunities lie. However, Turkey’s move east may increase the prospect of a confrontation with Russia by encroaching on Moscow’s traditional zones of influence and control. The most obvious manifestation of this strategy was Turkey’s role in the recent Artsakh War. Azerbaijan was already a critical element in Ankara’s plan to wean itself from its dependence on Russian gas and in mid-2020 had overtaken Russia as Turkey’s main gas supplier. Turkey was able to leverage the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia to consolidate its burgeoning alliance with Azerbaijan, while also “muscling into Russia’s backyard.”

Turkey’s “Looking to the East” foreign policy is nothing new. Turkey waged battles and war against Russia during World War I to conquer Central Asia but failed. Seventy years later, with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, taking advantage of the political vacuum and weakness of Russia, Ankara set on revitalizing the idea of Pan-Turkic solidarity to build an alliance across the Caucasus and Central Asia. Underpinning this policy were the perceived linguistic, cultural, religious, ethnic, and historical links with the Turkic people of Central Asia. This policy was orchestrated by late Turkish President Turgut Ozal and later adopted by President Erdogan. With AKP’s (Justice and Development Party) rise to power, Ankara has been striving to build a stealthy but important strategy towards Central Asia. Seckin Kostem, an assistant professor of International Relations at Bilkent University, argues that while geopolitical consideration has formed the backbone of Turkey’s renewed interest in Central Asia, economic pragmatism and the domestic turmoil in Turkey have also shaped its strategy in the region. This article will highlight how Turkey used soft power diplomacy to infiltrate the region and whether Ankara can balance its trade and geopolitical interests without clashing with Moscow and Beijing in Central Asia.

Turkey’s “cultural diplomacy” in Central Asia

For a country to assert its influence on a region, it has to employ “soft power” diplomacy. According to American political scientist, Joseph Nye, “soft power” is non-coercive (though it can lead to hard power) and includes culture, education, religion, and political values that involve the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Turkey institutionalized its “soft power” diplomacy with the Turkic-speaking states of Central Asia. This started through intra-Turkic cooperation and in 2009 developed into the Turkic Council composed of Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan. This organization’s policy aims to promote Turkic culture and facilitate trade between member states and was supported by the growing nationalist parties in Turkey.

Extraordinary Meeting of Foreign Ministers of the Turkic Council in Baku, February 6, 2020 (Photo: Facebook/Turkic Council)

Turkey expanded its influence to the newly independent countries of the region by capitalizing on common history and culture. Education was the most powerful weapon. Ankara actively supported the dissemination of Pan-Turkish ideology in the region by establishing Turkish educational institutions in Central Asia, offering scholarships for Central Asian youth to study in Turkish universities and participate in cultural exchange programs. In an exclusive interview with the Armenian Weekly, General Director of the International Institute of the Development of Science Cooperation (MIRNAS) Mr. Arif Asalioglu mentioned that Turkey has started intensive research and analysis among experts and scientists to create a model for the countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus. For this purpose, interstate contacts began to be established, and agreements were signed and various Pan-Turkic organizations were created.

Thus Ankara tried to export its “Turkish model” to Central Asia. Asalioglu argues that to fulfill its Pan-Turkic dreams Ankara welcomed “tens of thousands of students from the republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus to study in various fields.” As a result, in recent years Ankara has “recklessly tried to enter the post-Soviet space.” “Various institutions, such as the Center of Turkic Peoples, the Yunus Emre Cultural Centers, the Maarif Foundation, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), and imams as subordinates of the Council of Religious Affairs, became carriers of Ankara’s new ideology,” added Asalioglu.

Many Turkish schools and universities in Central Asia played a significant role in promoting not only the ideology of Pan-Turkism but also providing Islamic education. Turkey’s main aim was to infiltrate the top-level government positions in Central Asian countries and try to bring a pro-Turkish leadership. As a result, from 1991 to 1999, 29 schools were established in Kazakhstan, 18 in Uzbekistan, 13 in Turkmenistan, 12 in Kyrgyzstan and five in Tajikistan (a non-Turkic country). More than 16-thousand students attended these schools. However, since the failed coup attempt of July 2016, Ankara has pressured Central Asian governments to close down dozens of schools operated by the Gulenists. Hence Turkey’s image was tarnished, and many teachers were deported.

Finally, not all Turkic states, excluding Azerbaijan, encouraged Pan-Turkic nationalism in their countries. Kazakh commentator Talgat Ibrayev stated that re-animation of the ideas of Pan-Turkism is threatening Central Asia. He added that these ideas are “a powerful consciousness-raising weapon” that can be used by radical nationalist groups and can pose serious security problems. The adherents of these ideas such as the Alash National Freedom Party in Kazakhstan are pushing to replace the Cyrillic alphabet with a common Turkic based on the Latin script. Some also viewed Pan-Turkism as suspicious; in 2005, Kazakhstan banned the ultranationalist Turkish Grey Wolves organization classifying it as a terrorist group. Uzbekistan also took a similar path and banned the Pan-Turkic Unity People’s Movement (Birlik) for “illegal activities.”

Navigating between trade and geopolitics

Turkey’s trade (mainly energy security) and geopolitical interests towards Central Asia are revolutionized through its domestic political transformation. Turkey’s engagement in active policies towards the region accelerated due to ideological reasons motivated by Erdogan’s coalition partner: the Pan-Turkic Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). Both parties are trying to mix the nationalist and religious philosophies in Turkey’s foreign policy. In the last few years, Turkey started to base its domestic and foreign policy on Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism. According to Asalioglu, during this period Turkey turned into a “mafia state, cooperated with terrorist organizations, threatened the world with terrorism, made racial aggression the only foreign policy instrument, and used it as an instrument of religious power.”

Any reorientation of Turkey’s foreign policy toward the Caucasus and beyond to Central Asian countries is not without risk. This will not go down well with Russia which considers this region as its traditional sphere of influence. To assess the present and forecast the future, we must go back in time and ask what Turkey has accomplished in both trade and geopolitical fields in the past 30 years?

Many Turkish economists believe that Turkey’s Middle Corridor, which goes through Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Caspian sea could complement Beijing’s New Silk Road. In November 2015, Ankara and Beijing signed a “Memorandum of Understanding on Aligning the Belt and Road Initiative and the Middle Corridor” at the G20 summit held in Antalya, Turkey. In 2019, China extended its currency swap agreement with Turkey, providing an additional $1 billion cash transfer to Ankara. By the end of 2019, the number of Chinese containers transported across the Caspian Sea via the Trans-Caspian Corridor increased by 111-percent compared to the previous year. On December 19, 2020, the first freight train carrying cargo from Turkey to China via the Trans-Caspian Corridor completed its historic trip.

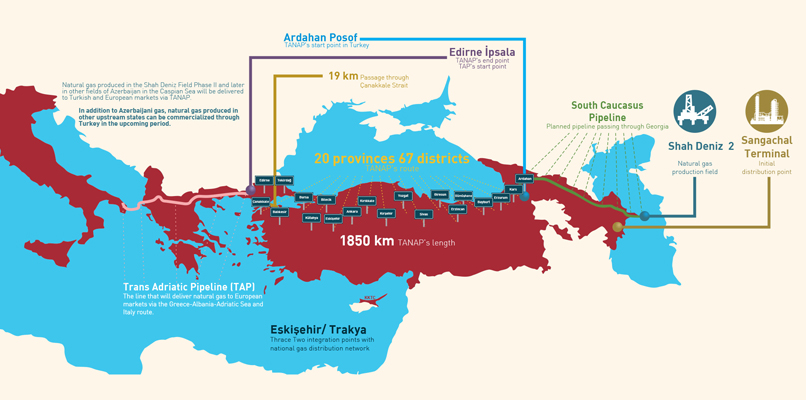

Meanwhile, to assert its role as a bridge between Europe and Asia, Ankara has planned to connect the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway, which was inaugurated in October 2017, to Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan through the Caspian railroads. Ankara also expects a growing amount of Kazakh oil to be pumped through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline shortly. Similarly, Ankara hopes the Turkmen gas will be connected to the Southern Gas Corridor through the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP). For this purpose in January 2021, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan signed an agreement to pave the way for the transit of Turkmenistan’s massive gas reserves to Europe via Azerbaijan and link it to TANAP. Thus Turkey would aim to become a transit gas corridor between the East and the West. However, all these initiatives may fail given Kazakhstan’s and Turkmenistan’s dependence on Russia and China, respectively.

Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline project (Map: http://www.turkishthinktank.net/)

After the recent war in Artsakh, the interest of some Central Asian experts grew towards Turkey to the point where Kazakh economist Saparbay Jubayev recently told Anadolu Agency that connecting Nakhichevan to Azerbaijan proper via a trade route – based on the November 9 ceasefire statement – would strengthen Central Asia’s geostrategic position. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have ports on either side of the Caspian Sea for cargo ships to dock, and Jubayev said that this is a “great opportunity to directly transport cargo from Europe and China by bypassing Russia or Iran.” Thus, according to the economist, reaching Central Asia and China will be easier for Turkey, while Kazakhstan will expand its way out to the Mediterranean and Europe via Turkey. Most importantly, it will increase travel and trade between Turkic states.

Despite Turkey’s intensifying energy security ties with the region, Turkey’s economic ties with Central Asian countries remain limited. Turkey’s trade volume with the five Central Asian states was $8.5 billion in 2019 which amounted to a mere 1.5-percent of Turkey’s total foreign trade, even though four-thousand Turkish companies (mainly construction) have been operating there. Turkish companies were active in building Turkmenistan’s Turkmenbashi International Seaport on the Caspian to facilitate trade between the two countries. However, Turkey is striving for more, and in the long run it may push its geopolitical designs too.

Geopolitically, Turkey no longer sees the US and the EU as crucial partners in Central Asia. Instead, Turkey, for the time being, is moving closer to Russia and China. Turkey has accepted Russia’s traditional sphere of influence in the region and is trying to penetrate Central Asia without antagonizing Russia, at least for now. With regards to China, Turkey has set aside its Pan-Turkic aspirations and championing the “Uyghur cause” in favor of Chinese investments in Turkey’s infrastructure. It is no secret that China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will revive Turkey’s bridging role in Eurasia. The Uyghur community in Turkey is feeling abandoned. In January 2021, the Extradition Treaty was signed between Turkey and China. Director of the Istanbul-based Uighur Academy Alimcan Inayet stated that Uyghurs in Turkey are worried, and their organizations that had engaged in political activism for “the East Turkistan cause” have found themselves increasingly under pressure.

But Turkey still has some space to maneuver, and Asalioglu argues that Ankara will challenge Moscow and Beijing in the imminent future. Turkey has used the Turkic Council as an instrument to extend its political and military influence in Central Asia. Significantly, Turkey is also pursuing a program of defense cooperation with the two largest Central Asian states, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which presents a direct challenge to Russia. Kazakhstan, a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a military alliance led by Russia, has entered into a military cooperation agreement with NATO member Turkey that encompasses the defense industry, intelligence-sharing, joint exercises, information systems, and cyber-defense, as well as military training and military scientific and technical research. Russian RIA Novosti reported that Kazakhstan is considering buying the Turkish TB2 (Bayraktar) drones instead of the Chinese ones after the former’s success on the battlefields in Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. In November 2020, a Kazakh military delegation visited Turkey’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems Base Command in Batman for several days to view the latest Turkish UAVs. After Azerbaijan and Ukraine, Kazakhstan would be the third former Soviet country to purchase these drones.

For Kazakhstan, the deepening of cooperation with Turkey, for example, could be needed to obtain a sort of balance in its relations with Moscow. According to Turkish state news agencies, some Kazakhstani elites are concerned about Russian policy towards Ukraine and feel insecure about the northern provinces populated by ethnic Russians in Kazakhstan. Turkish media is inflaming the anti-Russian climate in the country. Recently an anti-Russian article was published in TRT World by Mansur Mirovalev raising the following question: “Should Kazakhstan fear a Crimea-style Russian invasion?” aiming to incite anti-Russian feelings in Kazakhstan. It is worth mentioning that TRT has launched a Russian language news platform intending to address the Turkic people in Russia. To avoid a “Ukrainian scenario” Kazakh leaders had been attracting “Oralmans” (ethnic Kazakhs from China, Afghanistan and Central Asia) in order to resettle them to bordering areas with Russia where ethnic Russians are a majority.

Uzbekistan also signed a similar agreement with Turkey in late October 2020 during a visit by the Turkish defense minister. Some observers argued that this visit may raise certain debates about the creation of an “Army of Turan” and a NATO-style military bloc of all Turkic-speaking states led by Ankara. Though unrealistic for the time being, these initiatives, all of which appear to be conducted in stark defiance of Russian interests given they are directed at countries historically within Moscow’s orbit, suggest that Ankara is heading on a collision course with Moscow rather than towards a detente. According to Connor Dilleen, an expert in international affairs, while Russia may have tolerated confrontations with Turkey in Syria and Libya, where their proxy armies have been in direct conflict, it’s likely to be less tolerant of Ankara’s maneuverings in its backyard. But what would prevent a new scenario similar to Nagorno-Karabakh from being repeated in Central Asia?

Assessing the risks

Russia and China have been the most powerful political and economic actors in Central Asia. Turkey may try to walk a fine line in improving relations with Central Asian countries without harming its relationship with Moscow and Beijing. However, Moscow has its limits too and would not tolerate Turkey swimming freely in its backyard again. China also would be very cautious to give space for Turkey in the region fearing that any cultural or political connection between Turkey and the Xinjiang province (bordering Central Asia) where Uyghurs are concentrated may agitate Turkic nationalism and destabilize northwestern China. Moreover, as Central Asia is seeking ways to reduce its dependence on Russia, and rethinking new options, Turkey is directing its investments from Western markets to Central Asian ones, particularly Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, which Ankara considers useful economic partners due to their rich natural resources. As we have seen in the Middle East, North Africa and the South Caucasus, Turkey pushes its trade and geopolitical interests in parallel.

Asalioglu believes that the ideas of “Great Turan” is utopian since Erdogan is trying to achieve his goals within the framework of an “unbalanced power policy.” The reason for this belief is that unlike the great powers, Turkey has neither the technological equipment nor the defense power to change the current regional order in Central Asia. Even though Turkey’s active participation in the Nagorno-Karabakh war created a new status quo in the region, which strengthened the strategic link between Ankara and Baku, Turkey now is in a position to challenge Russia as the leading power in the Caucasus and maybe beyond. Erdogan’s political ambitions will only generate conflict. Thus, Russia and China are careful and attentive to such endeavors and will hold back Ankara’s enthusiasm.

Nevertheless, such political adventures are full of challenges and whether Turkey has calculated the risks is still unclear, leading to some serious questions. To what extent can Turkey push its Pan-Turkic aspirations in Central Asia? If Turkey’s economic and energy relations in Central Asia continue to deepen, will it inevitably increase engagement on security issues as a means to protect them? Will Russia and China tolerate a NATO member exerting its influence near their traditional zones of influence? Turkey has growing trade relations with China, and to some extent energy dependence with Russia, and a traditional security alliance with the United States. Should these powers start to aggressively compete with one another over the sphere of influence in Central Asia, will Turkey be able to preserve and balance its interests in great power politics? Time will tell…

The article was originally published in the Armenian Weekly, 17/2/2021

Yeghia Tashjian is a regional analyst and researcher. He has graduated from the American University of Beirut in Public Policy and International Affairs. He pursued his BA at Haigazian University in Political Science in 2013. He founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog in 2010. He was a Research Assistant at the Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the Regional Officer of Women in War, a gender-based think tank. He has participated in international conferences in Frankfurt, Vienna, Uppsala, New Delhi, and Yerevan, and presented various topics from minority rights to regional security issues. His thesis topic was on China’s geopolitical and energy security interests in Iran and the Persian Gulf. He is a contributor to the various local and regional newspapers and presenter of the “Turkey Today” program in Radio Voice of Van.